Editorial | Mar 26,2022

Oct 19 , 2019

By Bula Sirika Wayessa (Ph.D.)

Ethiopia must be prepared to regulate the public intake of sugary foods and beverages by enforcing mandatory policies that restrict its presence in their population’s diet and fight to break the cycle of dependency and attain food self-sufficiency, argues Bula Sirika Wayessa (Ph.D.) (wayessa.bula2009@gmail.com), whose research interests include small-scale agriculture, commercialisation and globalisation of natives crops and the implications for small-scale farmers.

When it comes to Africans and people of African heritage, sugar is always seen as a commodity whose bitterness often overshadows its sweetness. Sugar may be sweet, but its bitter historical association with slavery and colonialism is directly linked to modern factors of land dispossession and rural poverty in the neocolonial era.

Sugar plantations fueled a barbaric form of slavery in which Africans were snatched from their mother continent by the millions in a process that lasted for nearly five centuries. Africans endured physical exploitation and psychological and emotional torture that left the continent and its diasporic community in a state of disarray that is still ongoing. Now, the continent that suffered most from slavery has become the victim of a new form of economic colonialism.

With few nutritional benefits, sugar poses a risk to wellbeing that has transformed the sociopolitical lives of societies all over the world. There is a consensus among scientists that links the caloric intake of sugary food and the rise in non-communicable diseases such as obesity, diabetes and cancer.

Africans and African diasporic communities are not only suffering the effects of economic colonialism, but they are also disproportionate victims of sugar-related non-communicable diseases. In the United States, they are over-represented in the national figures on obesity, diabetes and related ailments – often because they live at the poorer end of society, where medical provision and healthcare are at their worst in otherwise developed societies or do not exist at all in underdeveloped third world countries.

A recent study also shows a drastic rise in obesity in urban Africa due to the rapid rate of urbanisation. Therefore, obesity rates and associated diseases will increase along with urbanisation. The growth of cities is linked to changes in lifestyles in developing countries, because sugar-sweetened food and beverage consumption is higher in urban centres.

It is described as a silent epidemic spreading throughout Africa – which has the highest rate of urbanisation of any major continent. Some see obesity as being more dangerous than HIV. Obesity is a major economic and healthcare challenge that strains resources, diverts public expenditure, and fuels other social problems for countries that can least afford the added financial burden. Strikingly, roughly half of the world’s twenty countries experiencing the most rapid rise in adult obesity are in Africa.

In the neocolonial era, sugar-related projects throughout Africa are linked to the displacement and impoverishment of already disadvantaged subaltern peoples. In the second half of the twentieth century, in collaboration with Dutch company Handlers-Vereeniging Amsterdam, Ethiopia established the first sugar factory in the Awash Valley in the eastern Ethiopian lowlands. Since the 1950s, sugar plantations in Ethiopia have been linked to environmental pollution because of the indiscriminate use of chemicals to control pests, the excess use and emission of fluoride from the refineries into the environment that affects the health of people and their livestock, and forcible displacement via land grabs that impoverish rural peasant communities.

Most of the sugar plantations in Ethiopia have been established in lowland areas, which are occupied by subaltern, semi-pastoral nomads who have lost their land to the plantations and find their rivers and streams polluted by chemicals discharged from the refineries because of the unsupervised use of insecticides and loss of grazing land due to sugar planting. It has been reported that during the 1970s, pastoralists along the Awash in the eastern and central Ethiopian lowlands lost their grazing land because of hydroelectric projects, and during the drought that followed, they lost three-quarters of their livestock because of the diverting of water upstream to irrigate the sugar plantations.

In the 21st century in the Lower Omo Valley, dams and sugar development projects have deprived the people of their customary lifestyles by limiting their access to natural resources in the valley on which they relied for generations. The Ethiopian government justified this act of dispossession by claiming that the land was being inefficiently used and was in most part idle. The government claimed that it was improving the lives of the locals through the voluntary resettlement of poor households into planned villages where they would have better education and healthcare services to replace their poor nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyles. These promises were broken, people were left helpless and formerly self-sufficient producers were forced to join the labour market with poor pay and no job security.

Despite this huge social and economic cost, not all sugar-related products have been successful, and failures have left Ethiopia and many other African countries burdened with debt from foreign loans while displacing tens of thousands of smallholders from their land due to poor planning and implementation.

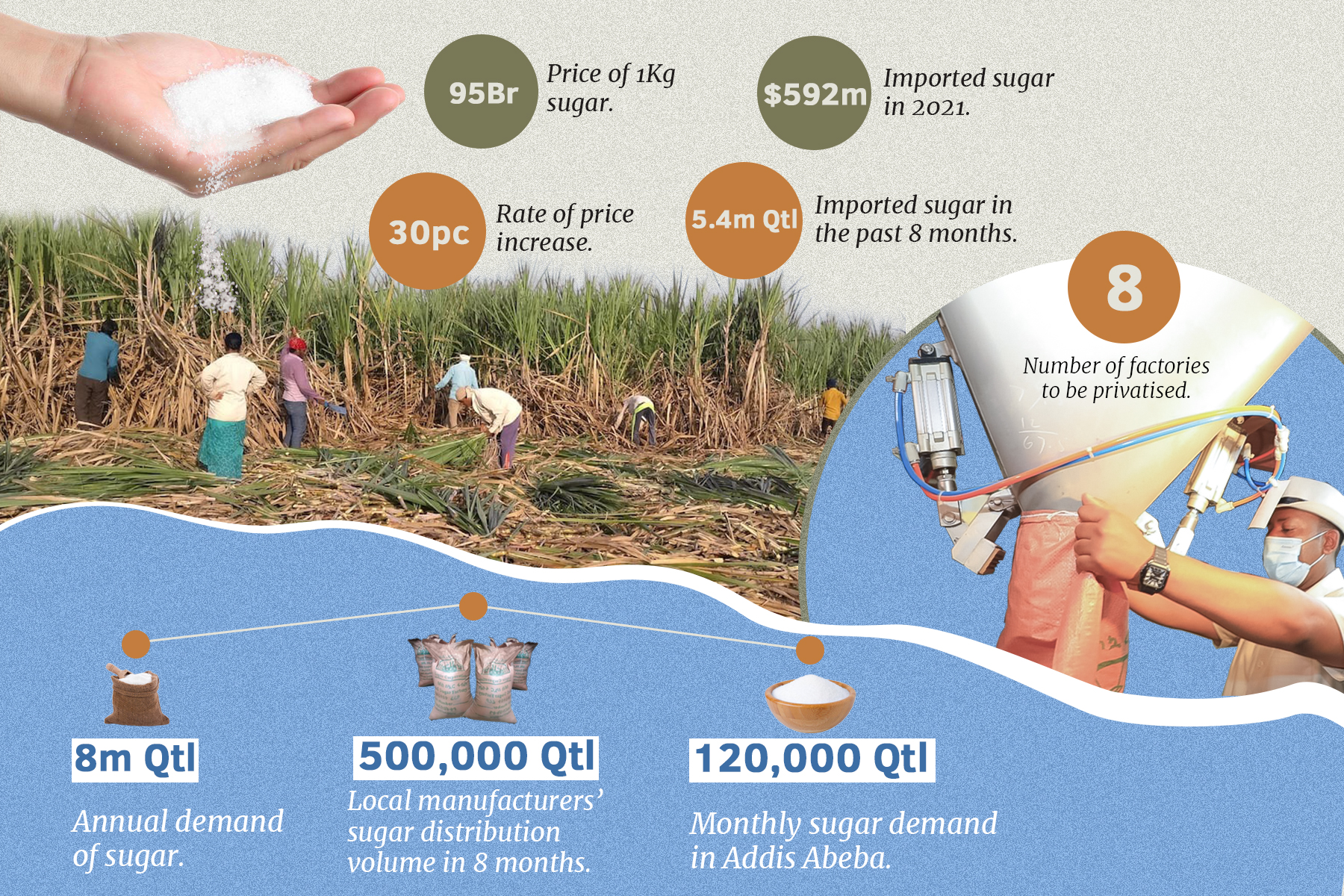

At present in the Omo Valley, only around 82pc of land cleared after displacing peasants for sugarcane has been cultivated. Due to the failures observed in these projects, the Ethiopian government has decided to sell its sugar refineries to private investors with no clear plans in place to tackle the challenges being faced by the forcibly displaced people.

To date, Ethiopia’s reliance on imported sugar continues to grow as the public’s craving for sugar is rapidly growing. The government offers subsidies and rations sugar by distributing supplies throughout the country. This is in marked contrast to other countries including South Africa where the government levies taxes on sugar to curb the growing rate of sugar intake among its population.

Given the public craving for sugar, the absence of any strict control on the use of sugar in domestic confectionery and beverage processing factories and government subsidies on sugar, the risk of sugar-related non-communicable diseases is on the rise in Ethiopia.

While investment in sugar projects is attracting the Ethiopian government, it appears that less attention is given to the necessary production of food grain, other than encouraging those smallholders that are left to modernize their farming systems. This means that Ethiopia must now import cereal crops such as wheat. There is no sound reason to justify why Ethiopia is forced to focus on sugar plantations instead of food grain production – except that sugar production brings money via development aid from western nations.

Sugar is a controversial commodity, and for Africans and people of African heritage, the commodity tastes both bitter and sweet. Ethiopia must be prepared to regulate the public intake of sugary foods and beverages by enforcing mandatory policies that restrict its presence in their population’s diet, which may include imposing a tax on sugar and sugary foods to discourage the public from over-consumption. More importantly, by safeguarding the country’s natural resources and prioritising its national interests, Ethiopia must fight to break the cycle of dependency and attain food self-sufficiency.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 19,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1016]

Editorial | Mar 26,2022

Fortune News | Apr 06,2024

Agenda | Sep 22,2024

Agenda | Apr 06,2024

Radar | Aug 05,2023

Radar | Sep 10,2023

Radar | Oct 05,2019

In-Picture | Oct 05,2025

Life Matters | May 13,2023

Fortune News | Jun 22,2024

Photo Gallery | 176120 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 166334 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 156782 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136876 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...