Jun 21 , 2025. By Ahmed T. Abdulkadir ( AhmedT. Abdulkadir (ahmedteyib.abdulkadir@addisfortune.net) is the Editor-in-Chief at Addis Fortune. With a critical eye on class dynamics, public policy, and the cultural undercurrents shaping Ethiopian society. )

It is stating the obvious to claim Addis Abeba is placed foremost in the economy, playing the protagonist, director and banker of national growth. The data affirms this louder than any.

Though the capital houses only three percent of the population, it produces 29pc of urban GDP and nearly a quarter of national output. Glass towers line Africa Avenue (Bole Road), fountains spray at Meskel Square, and highways speed commuters across the city, while coffee growers in Kaffa still pull timber and beans over dirt tracks to markets they barely reach.

That gap is no accident. Ethiopia’s development model follows a core-periphery script. The centre collects infrastructure, talent, and power, while the regional states supply raw materials, labour, and land without proportionate investment. Unequal-exchange theory calls it a one-way flow of surplus. Even the World Bank, not known for flattery, said the “rising tide” of growth “failed to lift all boats.” From 2005 to 2016, the bottom 40pc of rural Ethiopia saw no gain in per-capita consumption.

Concentrating growth in a single city makes the economy brittle. The Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA) reports widening regional gaps, with the capital and a few favoured zones absorbing the majority of the federal government's capital spending. Vast areas remain untapped because they lack roads, clinics and electricity. Ironically, the federated states fund progress that they do not use.

The city’s dynamism also drains talent. Students, engineers, doctors and civil servants stream into Addis Abeba, turning regional towns into feeder hubs. The private sector vacuum also siphons ambition from secondary cities. Youth from Gondar, Dire Dawa, and beyond are drawn to the city, while teachers and civil servants from regional states seek transfers here. The periphery bleeds talent, ironically reinforcing the elite narrative that Addis Abeba must centralise resources because "the rest of the country has no skilled labour." It sounds like a self-fulfilling prophecy.

For many migrants, the switch is bittersweet. Escaping rural poverty often means replacing it with crowded housing and informal work. A recent demolition drive on the city’s edge displaced more than 100,000 low-income residents, showing how projects that beautify boulevards can uproot the workers who built them.

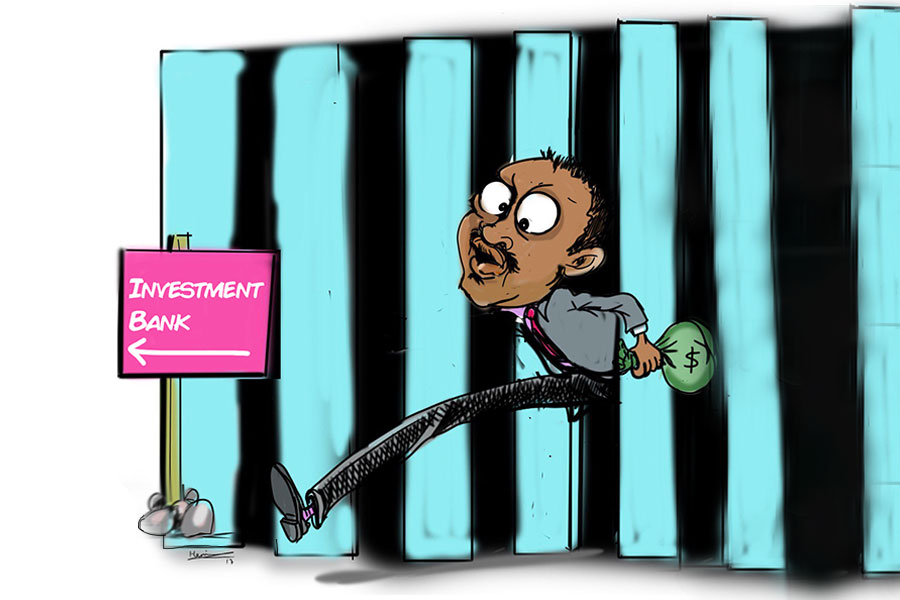

Capital follows pavement. Investment flows “as smoothly as a Sheger boulevard,” while infrastructure-poor but resource-rich states, such as Kaffa Zone, struggle to attract credit. In the eight years beginning in 2013, the rural population rose by 24.4pc, outpacing a 20.8pc rise in rural-to-urban migration. Rural Ethiopia grows faster than it urbanises, deepening a paradox. Prosperity clusters in the capital even as countryside hardship widens.

Attempts to spread industry often leave control in Addis Abeba. An industrial park may sit in Hawassa or Kombolcha, but cash and command still run through companies and firms headquartered in Addis Abeba. Local governments become spectators despite constitutional promises of self-rule and fiscal decentralisation. And numbers tell the story.

Only 57pc of districts in the Somali Regional State are reached by asphalt; coverage is lower in the Afar Regional State. Yet, the capital presses ahead with light-rail extensions, new terminals and beautification drives. Urban glamour is evident in Unity Park and along the main manicured roads, while clinics in Gambella Regional State lack access to clean water, and children in Benishangul Regional State walk for hours to school.

Policy moves from the centre can feel punitive at the edges. Currency depreciation and subsidy cuts planned in Addis Abeba reach villages in regional states not as reform but as higher food prices and the risk of drought. Systems theory would call it a feedback loop. Central nodes grow stronger as peripheral ones depend on them.

Leaders in Somali Regional State may say currency moves and subsidy cuts are drafted “without even a post-it of consultation.” Officials in Afar Regional State could voice similar complaints when decisions about freight tariffs or fuel prices arrive by circular from Addis Abeba. Such top-down governance, they could argue, treats local administrations as mere extensions of the capital rather than elected governments.

Even agencies meant to devolve resources often retain their senior managers and budgets in the capital, leaving regions with little say over projects on their own soil. The imbalance shows up in hard data. The Gini Coefficient index is climbing, and resentment in the hinterlands rises with it. The growth story risks resembling “accumulation by extraction,” with airports, rails, and green parks financed by resources from neglected districts.

Addis Abeba’s brand machine nonetheless sells optimism. Billboards hail the capital as a “Renaissance City”; its skyline is used as shorthand for national progress. Drought or hardship in rural zones rarely command the same airtime as a ribbon-cutting downtown. Symbolism, like tarmac roads, is unevenly laid.

Officials appear enthusiastic about digital transformation, achieving middle-income status, and new investment corridors. Critics argue that before the country wires itself for fintech, it should pave the way for Kaffa and give regions a voice in setting the plan. The hinterlands hide billions in potential output; unlocking it would enlarge, not diminish, the capital’s fortunes.

Over-centralisation is not merely unjust; it is inefficient. Hoarding talent and capital leaves much of the country underused and weakens the base needed for lasting growth. A strategy that channels money beyond the ring road, equips regional schools and hospitals, and lets local leaders set priorities could turn millions of spectators into stakeholders.

The cranes over the capital's skylines could serve as a pathfinder to what the whole country could become. The challenge is to ensure those towers cast light, not shadows, on the lands that sustain them.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 21,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1312]

Photo Gallery | 139545 Views | May 06,2019

My Opinion | 134032 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 130587 Views | Aug 21,2021

Photo Gallery | 129801 Views | Apr 26,2019

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Aug 16 , 2025

A decade ago, a case in the United States (US) jolted Wall Street. An ambulance opera...

Aug 9 , 2025

In the 14th Century, the Egyptian scholar Ibn Khaldun drew a neat curve in the sand....

Aug 2 , 2025

At daybreak on Thursday last week, July 31, 2025, hundreds of thousands of Ethiop...