Editorial | Oct 11,2025

May 15 , 2021

By Brook Kebede

Throughout history, political campaigns have evolved around the advancing technologies available at the time. As technology develops, politicians can deploy them to disseminate their views. In Ethiopia, even though internet penetration and access to social media are in their infancy, they are fast becoming a tool for social movements. It is becoming popular among politicians and their organisations to broadcast political messages and build networks of support. For instance, in the past half a decade, African elections witnessed a massive rise in social media use during election campaigns by key political figures, parties and civil society organisations.

Social media provides significant benefits in a democratic election, allowing politicians to connect directly with the electorate. Unfortunately, it also can be used to threaten and undermine the integrity of the electoral process as activities are shifted from the regulated offline space to the less regulated online world. In this respect, the prospects and threats of social media in political communication across the globe cannot be overstressed.

The ultimate aim of a political campaign is to influence people’s perception and, consequently, voters' electoral decisions. In this regard, Facebook and Twitter could be used as an alternative to the mainstream media. This is a phenomenon peculiar to Ethiopian political experiences, which have been highly dependent on legacy media.

This has changed now. Social media, especially Facebook, may play a significant role in political mobilisation in the upcoming June elections. It will be used for active campaigning. For instance, politicians may utilise regular live streaming on Facebook as a way to interact with voters. The livestream may be used to keep voters informed about the policies and strategies of parties. This would especially be powerful for smaller, local politicians who need to address issues that might not be receiving mainstream news coverage. Social media may also be put to good use by regulatory bodies. The National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) has been using it to communicate information to voters and political parties.

This has provided new ways to stimulate citizens’ engagement in political life, where elections and electoral campaigns have a central role. It provided the means of connecting politicians and their parties, bringing party activities close to the electorate.

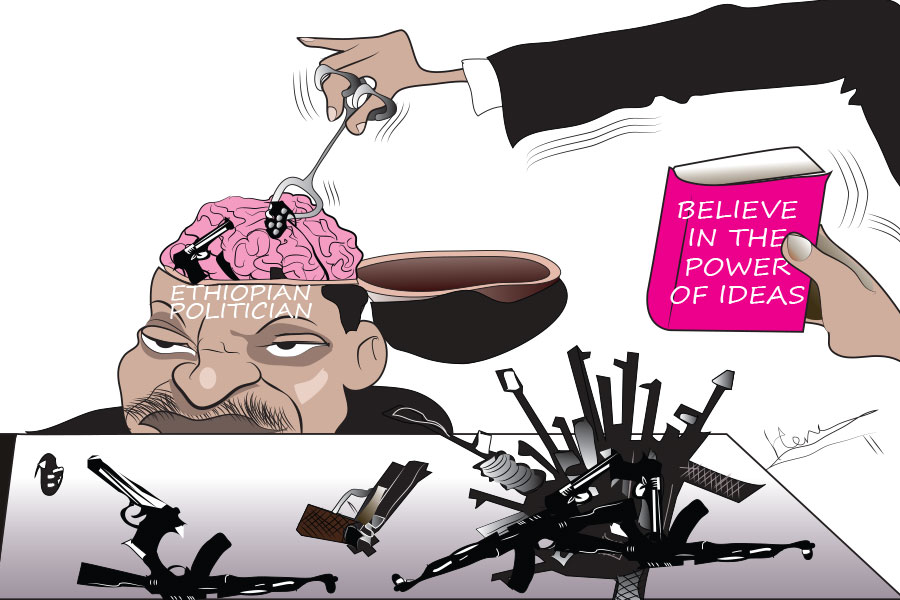

Indeed with the official start of the political election campaign, the activities of the political parties, candidates and their supporters have intensified and the discussions have heated up in Ethiopia. The input of social media into this has been questionable. It has come to contribute very little in terms of parties’ and candidates’ profiles, programs and positions, all of which are necessary for voters to make informed decisions.

Posts and messages on policy positions and political objectives are dominated mainly by discussions on which candidate is pulling the bigger crowds, personal attacks and ridicule, and all kinds of rumours and allegations of misconduct, manipulation and interference.

The nature of the discourse is not doing any good to Ethiopia’s political woes. Combined with the threat of disinformation, it can thwart the basic constitutional principles upon which democracy could be built. Whereas disinformation produces general harm that preys on the credulity of its audience, electoral disinformation’s harm is potentially more severe with implications for democratic principles and electoral integrity. It harms the voter’s ability to make an informed vote and participate in political debates.

It is not just in Ethiopia. The impact of disinformation and hate speech on the development of democratic systems of government, on the electoral process, and on social harmony are becoming evident in both developed and developing countries. The difficulty in tracing the sources of information and the extraterritorial feature of the technology further allows the dissemination of political campaign by foreign or domestic sources in violation of election rules much more problematic.

It is commendable that there have been some attempts at safeguarding against the harms of social media. One important law, which unfortunately has been barely utilised, is the Political Parties Registration and Electoral Code of Conduct. It provides standards that should be followed by candidates and supporters, members, agents, and officials of political parties during the election campaign, voting, and after results are announced. It requires candidates and political parties to conduct campaigns peacefully, respect the rights of competitors, respect the secrecy of ballots and cooperate with election officials and observers, and recognise and accept elections as expressions of the free and legitimate decision of voters.

However, the emergence of social media-related electoral campaign has challenged the capacity of the legal regime to further its intended goals. Indeed, a hate speech law had been enacted in the past year but its enforcement against something that offers an unprecedented amount of privacy and anonymity has hardly been effective.

Helpful in this regard is perhaps improved oversight from social media companies themselves. Facebook has, for instance, announced plans to increase accountability over social issues, elections and political advertisements in Ethiopia. It has adopted measures to keep users safe against misinformation and prevent abuse of its platform by removing accounts created to mislead people. There will be strict enforcement of its Community Standards to guard against incidences of inciting violence, hate speech, and harassment. It also invites citizens to use its reporting tools to flag any incidences that violate Facebook.

This is laudable. But it also needs to be mixed with increased vigilance, patience and discipline from the side of the public to minimise incidences of unrest and violence as a result of things that are said or shown on social media.

PUBLISHED ON

May 15,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1098]

Editorial | Oct 11,2025

Fortune News | Jul 13,2020

Viewpoints | Dec 08,2024

Radar | Nov 06,2021

Editorial | Jun 29,2019

Commentaries | Sep 19,2020

Sunday with Eden | Jul 08,2023

Advertorials | Aug 05,2025

Viewpoints | Mar 16,2019

Fortune News | Sep 21,2025

Photo Gallery | 175779 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165997 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 156397 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136844 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...