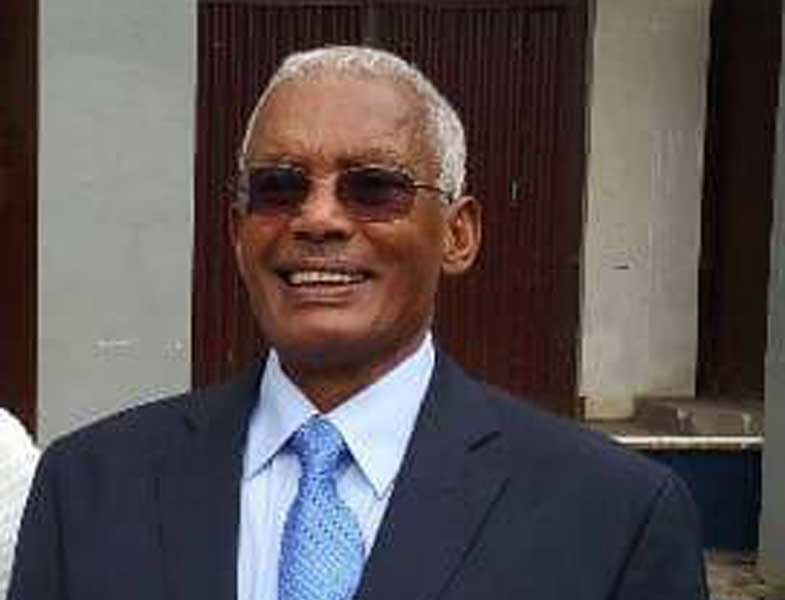

Obituary | Nov 29,2020

Sultan Hanfare Alimirah was not one to stand back when political issues arose. Just as in 1991, he was attentive and aware of the changes that were to lead to the new administration that brought Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) to power.

Still, he did not become oblivious as the years went on, and he became unable to serve the political movements with the same energy and force. He said as much in an interview he gave in 2016 to ESAT TV as anti-government protests were raging in the Oromia and Amhara regional states.

“I may not have the energy to run in the fields with you, but my heart is with you,” he said. “But neither would I stand by. Stay strong.”

He even offered some advice, which seemed to hint at how to get attention for anti-government protests. He said this was in relation to Afar Regional State, his birthplace and the centre of the Aussa Sultanate.

“Afar is positioned strategically. What happens in Afar reverberates in Addis Abeba,” he said. “What happens in Addis Abeba is heard globally.”

Indeed, Hanfare - who passed away on September 20, 2020, and was laid to rest a day later - lived a life rich with political activism. Having been born within an aristocratic family within the historic Aussa Sultanate, he may not have had a choice of whether to engage with politics to begin with. But to characterise him as a mere product of his ancestral background and upbringing would be to miss how politically conscious he remained throughout his 74 years.

“He was bold and politically oriented, which is one of the reasons he succeeded his father,” says Mohamuda Gaas, a childhood friend who later became state minister at various government agencies.

Mohamuda should know. He was with Hanfare, now survived by seven children, when they first became acquainted with injustice and embarked on activism. It was during the Imperial era when they met each other because of the student association they were a part of.

The establishment of the Awash Valley Authority formed the impetus for their political activism. The Authority’s mandate was administration and development of the natural resources of the Valley.

A big part of this was to be the “the development of commercial agriculture considered to have considerable scope for rapid production growth, and thus immediate impact on the entire economy,” as a paper by the Authority indicated.

Hanfare and Mohamuda believed that this was being effected through land concessions to investors that displaced farmers in the Awash valley.

“We decided to stand together for what we believed was an injustice against our people,” says Mohamuda.

But the political activities they were performing as students would gain greater urgency with the deposition of Emperor Haileselassie in 1974 and the rise to power of the Dergue. Relations between the new central government in Addis Abeba and the then Sultan, the long time ruler Alimirah Hanfare, also the founder of the Afar Liberation Front, began to sour because of the latter’s known sympathies for the deposed emperor.

The Sultan went into exile, as did Hanfare, who believed in the core questions of the Student Movement: land to the tiller, democracy and the equality of nations and nationalities.

During the Dergueyears, Hanfare became the chairperson of the newly formed Afar National Liberation Movement, joined by Mohamuda, who was political commissar.

“He was a nationalist, no doubt about it,” says Mohamuda, who describes his old friend as honest and daring.

Hanfare fit in with the nationalist rebel groups fighting against the Dergue. As the regime lost more and more of its grip on power, and when it agreed to participate at the famous US-mediated talks in London, Hanfare was there. In fact, for well over a decade, he seemed to have found common ground with the Ethiopian state since he took the mantra of the Student Movement during the Emperor’s reign.

For a year after Ethiopia became a federal republic and the Afar Regional State was established, Hanfare served as regional president and later as an ambassador to Kuwait. Arguably, his biggest claim to fame is his rise as head of the Aussa Sultanate, which is considered to have historical, traditional and spiritual significance to many residents of the Afar Regional State.

Although he succeeded his father as Sultan in 2011, the deterioration of his relationship with the government, a slow process that began in the early 2000s, meant that he had spent most of his time as Sultan outside of Ethiopia.

His support for anti-government protests by 2016, as described by him, was the end of a long process of political questions as to whether the people of the Afar region had been one of the most politically and economically disadvantaged groups in the country.

“The people of Afar didn’t benefit at all [during the past 27 years],” he told OBN, the state broadcaster, in an interview.

His body was laid to rest in Assaita city of Afar Regional State, with the presence of Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh, Tagesse Chafo, speaker of the parliament and Adem Farah, speaker of the House of Federation.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 03,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1066]

Obituary | Nov 29,2020

Obituary | Dec 19,2020

Fortune News | Oct 10,2019

Obituary | Apr 03,2023

Viewpoints | May 01,2020

Obituary | Jul 11,2021

Films Review | May 02,2020

Radar | Apr 29,2023

Obituary | May 23,2020

Films Review | Sep 19,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...