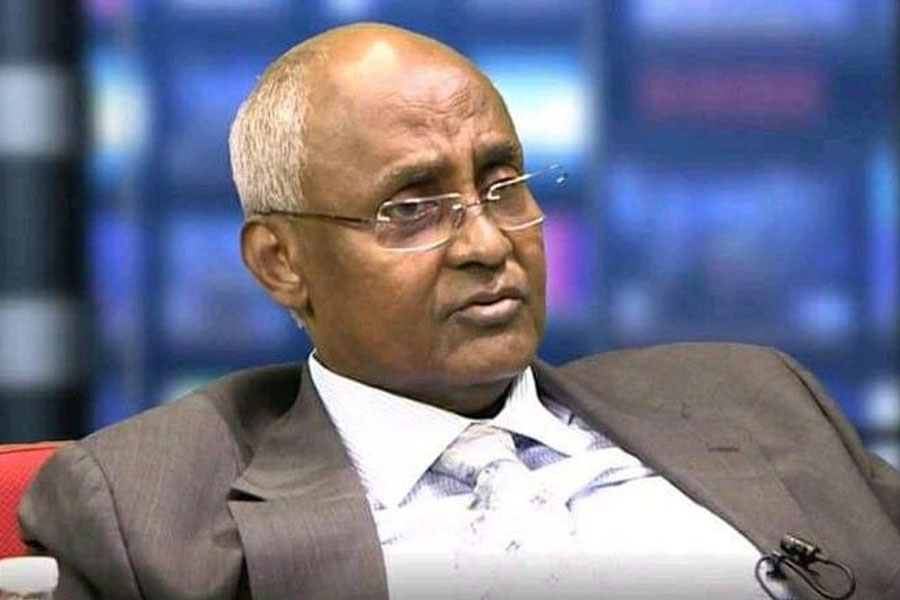

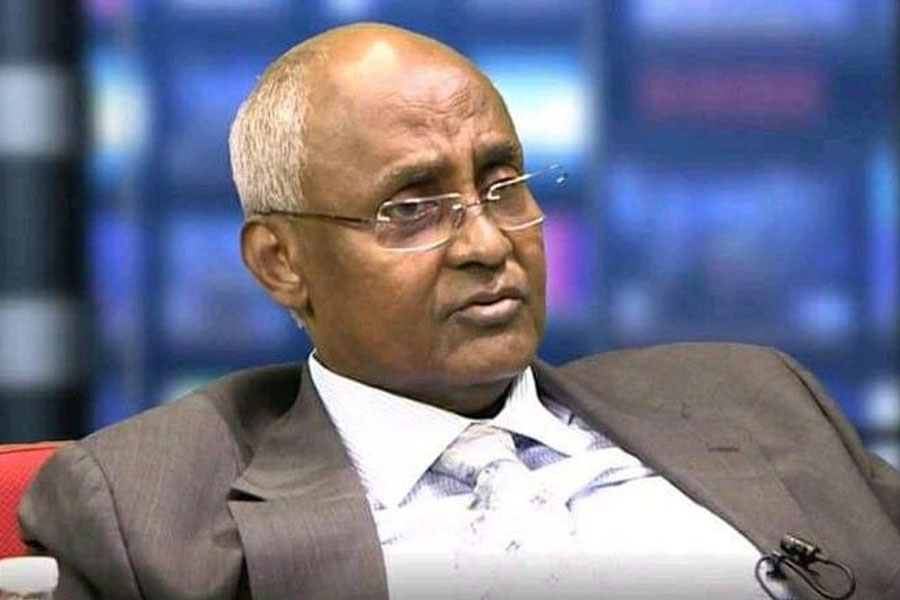

Obituary | Oct 03,2020

Mohammed Idris came to feel like a father figure to many that met him. Most striking was his effect on the younger generation. Part of this was that he had come to be known to many young people through his active engagement with Rotary Ethiopia, a nonprofit engaged in various humanitarian activities.

His passion paralleled that of the flagship project of the organisation, the eradication of polio across Ethiopia. Although he did not become a Rotarian until the last few years of his life, he worked in his personal capacity under the National Polio Plus Committee of the organisation.

“He was a polio warrior and an advocate for children’s immunisation,” World Health Organisation (WHO) Ethiopia stated on its Twitter account.

Mohammed was engaged in the fight against polio from as far back as 1996 when he began working with the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) of the WHO. He was engaged in the initiative when Africa was declared polio-free this year, though bouts of vaccine-derived polio persist on the continent, including in Ethiopia.

Abeselom Samson, a Rotary member, had the same impression and believed the organisation gained immensely from Mohammed’s contribution. Twice, the duo headed to Jigjiga for projects focused on vaccine-derived poliovirus, rare strains of poliovirus that have genetically mutated from the strain contained in the oral polio vaccine. Abeselom was witness to how working with the authorities and officials at health bureaus and NGOs became easier all of a sudden. Everywhere they went, most people recognised him and were eager to help.

“He had a knack for bringing people together,” says Abeselom. “All the doors opened for us. They responded very well to his humanity.”

How easily Mohammed befriended people and got along with them well to strike a lasting impression is typified by the relationship he had with Jemal Mohammed, the managing editor at a consultancy firm. The two met quite by accident. The former was trying to buy a house, and the latter was trying to sell one. They found each other through a middleman. It was only a surprise then that they would go on to become like father and son, in Jemal’s words, within a mere three years.

“My dad died when I was nine. He filled that void for me,” said Jemal, whom Mohammed used to call "my son."

Of note among his humanitarian work was also the school he founded — Daletti Primary School. While such humanitarian projects started only around the 1990s, founding the school was not a mere venture undertaken during the last chapter of his life. Having begun his career as an educator in the 1960s when he was posted in Jimma teaching primary school students, Daletti was his way of emphasising the importance of early childhood.

Mohammed, nonetheless, made his mark on areas outside of education and health. In fact, many recognise him as a journalist, having worked for ETV and catching the eye of nonprofit institutions needing his service as a communications professional.

Notable about Mohammed was also his rather high profile marriage to Bizunesh Bekele before her untimely death in 1990. They met during a social gathering and married despite them both practising different religions. It was a marriage that had been well-regarded for breaking social taboos by those that knew him.

It was thus unsurprising that his passing early this month roused emotions among the admirers of Bizunesh as it did from those in the education, health and humanitarian sectors. It was the breadth of his experiences and the diverse number of influential people that he knew that inspired his closest friends to plead with him to write an autobiography.

“He did not want to,” says his widow, Halima Musa. “He knew other people were going to. He believed so much has already been said."

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 17,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1068]

Obituary | Oct 03,2020

Fortune News | Oct 26,2019

Obituary | Feb 10,2024

Viewpoints | Apr 26,2019

Life Matters | Feb 06,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...