Editorial | Nov 11,2023

Oct 25 , 2025

By Abdul Mohammed

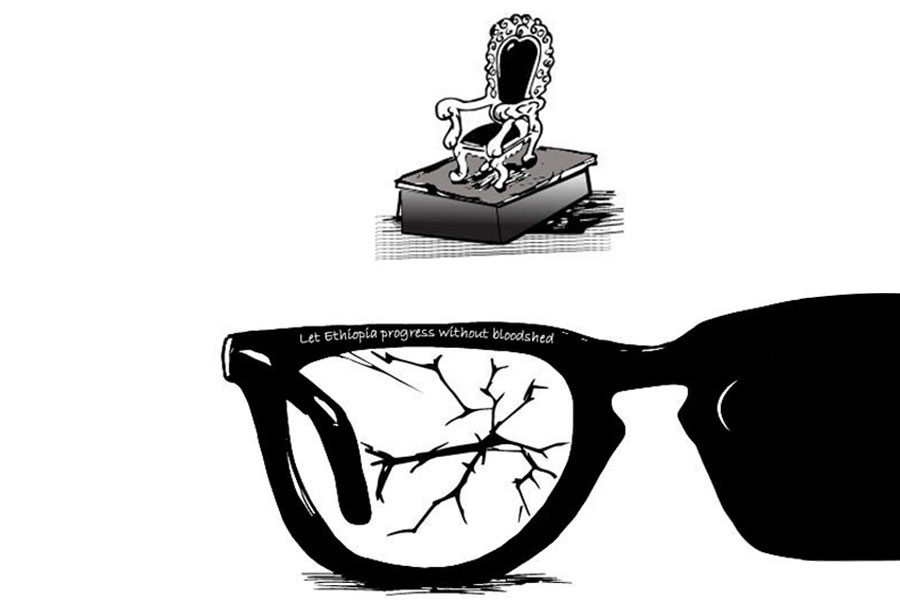

Sixty-two years after the African Union’s founding, its original vision of collective security faces new challenges. In today’s fragmented diplomatic arena, regional unity and early conflict prevention are increasingly sidelined, raising questions about the future of multilateral peacemaking.

In today’s conflicts, the announcement of a ceasefire is often celebrated as if it were peace itself. But these pauses in fighting - fragile, temporary, and often immediately violated – rarely resolve the disputes that caused the war in the first place.

From Gaza to Sudan to the Thai-Cambodian border, ceasefires have become the default endpoint of international diplomacy, rather than the first step in a sustained peace process. This is not only a symptom of our pessimistic political era. It should also be seen as a warning that the very idea of peace as a just and durable settlement is slipping out of the global imagination.

The Horn of Africa, one of the world’s most volatile regions, offers a revealing case study of this transformation, showing how principled and inclusive mediation has been displaced by transactional, interest-driven deals that manage conflict but do not resolve it.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of optimism followed the end of the Cold War. The United Nations (UN), regional bodies, and major powers pursued a 'liberal peace' model, seeking to end wars through democracy, inclusion, and the rule of law. African-led institutions such as the African Union (AU) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) embraced this approach, building mediation frameworks that treated peace as much more than the absence of violence.

The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in Sudan was emblematic of this era. Brokered by IGAD with AU and international backing, it combined security arrangements, power- and wealth-sharing, and democratic transition in a process that sought national ownership and international legitimacy. Though imperfect, it was rooted in the belief that peace required addressing political grievances, not merely silencing the guns.

Two decades later, that model seems a remote aspiration. Globally, the appetite for ambitious peacebuilding has waned. In their place, ceasefires have proliferated with short-term truces, humanitarian pauses, and ad hoc security understandings. But they are rarely linked to sustained political negotiations.

Under President Donald Trump, the United States has abandoned painstaking negotiation in favour of rapid bargaining, centring on a combination of commercial deals, strong-arming concessions, and a high-profile event at which the contending leaders shake hands and nominate Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize. This plutocratic and populist peacemaking did not spring from nowhere. Trump’s style accentuates an existing trend.

A recent example of a ceasefire elevated as an end in itself is the Gaza Agreement. The global outcry to stop the unfolding genocide was urgent and universal, demanding immediate action. Yet what emerged, shaped around U.S. President Donald Trump’s twenty-point peace plan, proved telling: only the ceasefire provision was pursued with vigour. The rest—particularly the political roadmap and the promise of Palestinian self-determination—remained vague, lacking both substance and commitment. Once again, a truce became the measure of success, while justice and lasting peace were quietly postponed.

The transactional turn has been evident in the Horn of Africa for a decade. In 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) and Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki made a pact that bypassed the UN, AU and Ethiopia’s own institutions. Presented to the world as a bold peace initiative, the deal ultimately led to other wars and triggered severe regional instability.

And the agreement that ended the fighting in Tigray Regional State in 2022 is a ‘Permanent Cessation of Hostilities’ and not a comprehensive political settlement, with vague commitments to human rights, democracy, or redressing the roots of the war.

Gulf and Middle Eastern states have since filled mediation roles once dominated by multilateral organisations. Backed by deep financial resources and security leverage, these actors favour elite bargains and security pacts over inclusive national dialogues. Their goals are to stabilise allies, secure strategic interests, and contain threats, not to transform the political relationships that drive conflict.

After the 2019 peaceful revolution in Sudan, negotiations to establish a new government were brokered by the U.S., Britain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, with the AU envoy providing a public face. Before long, the Arab states were clearly in the driving seat. When Sudan’s current war broke out in April 2023, talks convened by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia aspired only to a ceasefire. The AU and IGAD have been sidelined, and the UN has lowered its ambitions to pushing for humanitarian access.

We see similar patterns in South Sudan and Somalia, negotiations to scale back on the fighting without formulating lasting solutions. This is the ‘negative peace’ trap, silencing the guns but not listening to the voices of the people who demand more.

Most agreements to cease hostilities are neither written down nor permanent. More formalised ceasefires and humanitarian pauses are the most likely to be followed by renewed violence. Best practice for a ceasefire, as laid out for example in the handbooks for the UN’s mediation support unit, includes third-party monitoring, mechanisms for handling complaints, steps towards consolidating the end to violence, such as exchanging prisoners of war and hostages or withdrawing heavy weapons to designated zones, and building confidence for political talks.

Without this, and especially without a credible political process, a truce may be a breathing space for combatants to regroup, rearm, and reposition.

By definition, belligerents believe the worst of each other. Ending a war requires building trust. The mediator tries to do this by facilitating direct communication between the warring leaders and by establishing robust mechanisms for monitoring, verification, and enforcement. For as long as the two sides continue to distrust each other, they need to have confidence in a reliable third-party mechanism.

And if peace is to last, the causes of the war and the grievances that accumulated during the fighting must be addressed.

The United Nations’ New Agenda for Peace and the African Union’s Peace & Security Architecture were designed with these goals in mind, along with early action to prevent armed conflict from breaking out in the first place.

Ad hoc transactional peacemaking has discarded these hard-learned lessons and bypassed the mechanisms that made them work. To be clear, multilateral peacemaking was always imperfect. It seemed time-consuming and cumbersome, and large UN peacekeeping operations were expensive and often ineffective. But the alternative of fragmented mediation initiatives, floated by rival powers candidly pursuing their own particular interests, without the apparatus for monitoring and verification, has a far worse record.

Most worrying is that peace without democracy and human rights, which legitimises and rewards those who led the fighting, is not sustainable. Some leaders may wish to return to the era when princes could sign pacts to divide countries and decide the fate of the people who lived there, as though citizens were mere tenants who could be served an eviction order. We have seen this in the Horn of Africa, and it is a future that does not work.

The Horn of Africa might seem the toughest place to reverse the current trend towards fast, transactional and performative peace. It has complex conflicts that take deeper root with every cycle of violence, and outsiders who meddle for cynical gain. By the same token, there is an unparalleled experience in peacemaking in the region, with a generation of diplomats and peace organisations. We know what works and what does not. The international context may have changed, but the basic formula for peace endures.

At the heart of peace is legitimacy. Peacemaking repudiates the mantra that might is right. Every state in the Horn of Africa is a member of the African Union, and, upon joining the Union, it committed itself to democracy, human rights, and the inclusion of diverse groups within its state. Since the African continental organisation was founded 62 years ago, its raison d’être has been cooperation. Africa rises together or falls together.

And by working together, in accordance with the agreed principles, and by developing and applying a growing toolbox for conflict resolution, democratisation, and transitional justice, Africa has shown that it can end wars. Its mediators understand local political cultures. They can integrate their efforts with the UN, European Union, the Arab League, and others, reducing duplication and competition. They know that mechanisms such as national dialogue can move a post-conflict country towards democracy. When the African Union shows unity and resolve, it can make outside powers follow.

Today’s preference for ceasefires over settlements reflects a loss of confidence in real peace. Such despair has no historical basis. Even the most intractable conflicts can be transformed when inclusive, principled mediation is backed by political will.

The Horn of Africa stands at the front line of this struggle. Its fate will be a test not only of African multilateralism but of whether the world can remember that the end of war is not the absence of fighting but a collective effort to right wrongs and build more just and inclusive societies. What is needed is a restored moral ambition. Peace with justice should remain the goal, even in a world sceptical of grand settlements.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 25,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1330]

Editorial | Nov 11,2023

Editorial | Dec 19,2020

Agenda | Jun 18,2022

News Analysis | Jan 19,2024

Fortune News | Jan 07,2022

Commentaries | Dec 21,2019

Editorial | Jan 14,2023

My Opinion | Nov 20,2021

View From Arada | Sep 16,2023

Viewpoints | Jun 07,2025

Photo Gallery | 178342 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 168543 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159332 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137067 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...