Radar | Oct 26,2025

The temperature was almost 30 degrees celsius on a Tuesday afternoon last month. Motorcycles were everywhere, driving across the border between Kenya and Ethiopia but without any restrictions.

Security officers from both countries deployed to patrol the border were, seemingly, unbothered by their presence. Holding a lot of cash on hand, parallel market operators were openly exchanging currencies with buyers and traders who had travelled hundreds of kilometres to buy goods at an affordable price. Unable to withstand the hot temperature, traders sell items in the open air, leaving their shops empty. Almost. Merchandise items that could cost thousands of Birr in nearby towns are available for prices three or four times lower.

Welcome to Gambo, a quiet but active business hub located next to Moyale.

But its silence is odd for those who frequent the town. Abdulkader Ismael, 57, a Kenyan trader engaged in exporting cereals to Ethiopia, is one of them.

"It's a town whose activities were razed by ethnic conflicts," he observed, alluding that the situation is no different in Moyale. "Later, the pandemic disrupted everything."

The business slowdown has also been felt in other areas where cross-border trade among informal traders are the norm.

Farther east, the slowdown is apparent in Togochale, a town bordering Somaliland but locally pronounced as Tog Waajale. It is a cross-border trade hub 230Km from the Port of Berbera and 80Km from Hargeisa, the capital of the self-declared yet-to-be-recognised Somaliland Republic. Livestock, khat and camel milk are the biggest traded items that make their way to neighbouring Somalia, while mainly processed food items such as wheat products, canned fish and edible oil are imported.

Tog Waajale has a reputation as a hotspot for the parallel currency market, almost every bank in Ethiopia has a branch in this small town with a population of a little over 20,000. Residents attribute the fast depreciated Birr to the slowdown in the informal cross-border trade activities there.

Though prime Minister abiy ahmed (phd) and Kenyan president uhuru Kenyatta had inaugurated the Moyale one-Stop Border post in december 2020, it only went operational three months ago.

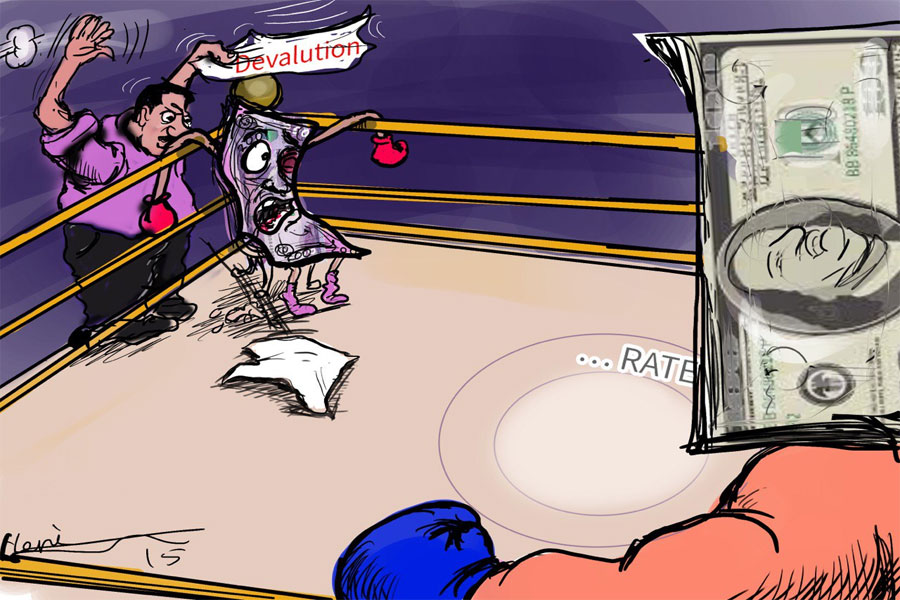

Belay Sisay, a customs officer at Tog Waajale checkpoint, observed that trust lately in Birr among traders of Somaliland has been falling as the currency loses ground against major currencies such as the Dollar, Euro and the Pound Sterling.

"This has impacted the trade activities on the border and Ethiopians who are doing business using Birr," Belay told Fortune.

Henock Shimeles, a businessman in Dire Dawa, 320Km from the border to Djibouti, has observed much the same thing. The state of emergency declared last year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic had disrupted trade, causing prices to spike and leading to a business slowdown. The price of a five-litre bottle of sunflower oil doubled to 500 Br last year.

"Problems with power outages on the railway have cost many khat traders," said Henock of the stimulant, which remains one of the country's chief export items, bringing in around 400 million dollars last year.

Up north, bordering Ethiopia with Djibouti, is the town of Galafi, a crucial entry to the logistic corridor to mainland Ethiopia. No less than 1,000 trucks, loaded with goods destined for both import and export, pass this route daily. Khat and vegetables such as tomato, onion, as well as fruits, make their way to Djibouti. Clothing, edible oil, and flour are the main items coming the other way through cross-border trading.

"Trade has slowed down since the outbreak of the pandemic," says Kebede Begna, head of the Galafi Customs Office, which collected over 10 million Br in duties last year.

These are incidents far from anecdotal relevance. The fall in informal cross-border trade activities was well documented in an UN-OCHA survey two months ago. Beans exported by informal traders of Ethiopia to Kenya showed a 43pc drop, reaching 2,677tn in the second quarter of this year. During the same period, the survey revealed that close to 34,250 camels were exported to Somalia and Somaliland by traders, representing a 19pc fall.

Abdulkader blames bureaucratic hurdles for the downward spiral of cross-border trade.

Located 774Km south of Addis Abeba, the Moyale One-Stop Border Post (OBSP) is a new development in the area. It started operation last June. Financed mainly by the African Development Bank (AfDB), the border post was expected to facilitate the movement of people and goods across the border, cutting down processing time by as much as 30pc.

The border regulatory officials clearing traffic, cargo and travellers from both Ethiopia and Kenya sit on either side of the border, where they undertake exit and entry formalities collaboratively. It is a much-heralded initiative peculiar to Moyale, which had attracted Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) and President Uhuru Kenyatta when it was inaugurated nine months ago.

However, the venture has yet to fulfil the promise, as witnessed by Abdulkader.

"The computer system is slow, and there's the language barrier," said Abdulkadir. "It's a tiresome difficultly we face on the Ethiopian side."

The cross-border trade is still reeling from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as immigration offices remain closed. Getting items such as cement, chickpeas and leather products with demand in Kenyan has become difficult. The same goes for khat, beans, onions and tomatoes. From the Kenyan side, manufactured goods such as shoe polish, agriculture chemicals, ballpoint pens, paper products, as well as livestock, cereals and produce are not moving at the regular pace.

This is a significant loss for Kenya; the trade balance tilted heavily in its favour. Last year, its exports to Ethiopia were valued at 71.5 million dollars, a positive trade balance of over 63 million dollars. However, the trade between the two countries has been declining for the past three years, consecutively, though this would have shown an improvement if current challenges had been addressed.

Daniel Koyech, a leather and hide products dealer, exporting to Uganda, is disappointed with supply shortages.

"The pause on immigration permits keeps me from reaching suppliers," he told Fortune. "Tariff rates also vary from officer to officer, affecting my business."

Joel Ndege, Moyale station manager of the Kenyan Revenues Authority, shares Daniel's misgivings. According to Joel, the absence of protocols and procedures that would allow small-scale traders to trade across the border legally is holding back potential. The traders active on the border are considered "smugglers" or, at best, "contraband traders."

Nonetheless, informal cross-border trade is a source of income to about 43pc of Africa’s population.

Urgessa Deressa (PhD), a lecturer of global studies and international relations at New Generation University College, believes governments should focus on developing legal frameworks and protocols for small-scale cross-border trade, as it has the potential to enhance relations with neighbouring countries.

"Regional governments should sign agreements to trade with local currencies," he said. "This will result in a significant change in filling the gap in foreign currency."

His view seems to be understood by the authorities.

Abraham Gudeta, the coordinator of international cooperation at the Ethiopian Customs Commission, disclosed that a legal framework to formalise small-scale trade across the border is underway.

“The protocol will be signed next week,” he told Fortune.

It is a piece of good news on the way to the residents of the border town of Moyale.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 10,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1115]

Radar | Oct 26,2025

Advertorials | Apr 08,2024

Agenda | Aug 17,2019

Fortune News | Nov 13,2021

Fortune News | Nov 18,2023

Commentaries | Dec 25,2018

Agenda | Aug 10,2025

Editorial | Dec 17,2022

Life Matters | Nov 20,2021

Fortune News | Mar 05,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...