Sponsored Contents | May 02,2023

Sep 1 , 2024

I believe most businesses in the city tend to be imitators, focusing on familiar sectors rather than innovating. The concept of a business plan is foreign, leading to stagnation, while only a few manage to survive the difficulties of the business world, writes Bereket Balcha (bbalcha5@yahoo.com).

Legend has it that James Bruce, a Scottish traveller and writer on a mission to find the source of the Nile River, once expressed his disdain for locals eating raw meat at the imperial palace in Gonder town. It landed him in pitch dark dungeon with a tiny window.

He was offered nothing but raw meat and Tej—a traditional honey-based alcoholic drink, during his banishment. Bruce reportedly shouted, "Bring me some more!" as he began to enjoy the delicacy. He grew so accustomed to the fare that he refused to leave the dungeon even when granted freedom. The monarch, seeing he had learned his lesson, continued serving him the treat, even when Bruce was hosted as a guest in the royal chamber.

For someone passing by the Ayat area, the numerous steak houses which feature raw or partially roasted meat seasoned with spices are hard to miss. For expatriates who have spent enough time in Ethiopia, the locals’ fondness for raw or lightly roasted meat seasoned with mitmita spice and mustard (senafich) is known. While this may shock some visitors, many eventually embrace the local cuisine.

Despite rising meat prices, the lively atmosphere quiets down only during fasting periods. The Roundabout, a major transport hub for railways and taxis, naturally attracts high traffic, making it a prime business location. However, I still find it difficult to fully grasp how so many steak houses thrive, maintaining profitability while offering high-end service by local standards. Another perplexing question is why all these establishments, located end-to-end, engage in the same business within a few blocks, in an area no larger than a square kilometre.

The success of the densely packed steak houses is primarily understood by their owners, who are willing to take the risk despite high rents and costs. Their profitability suggests that there is sufficient demand to sustain the business model, which has proven effective without the need for extensive feasibility studies. As long as enough customers are drawn to the area, the model continues to thrive.

Most businesses in the city prefer models that have already been tested and proven profitable. Few seem willing to innovate or invest in ventures where no one else has gone before. Once a business model proves feasible, similar ones proliferate, copying the same approach. There is no limit to the level of imitation and risk aversion; sometimes, this extends to setting up the same business next door.

It is not just the business model that ensures success, but the location as well.

It is not uncommon to see the same type of business replicated in the same area. Sometimes, I wonder if they are all competing for a share of the same pie, ultimately ending up with meagre profits.

I remember when my brother, a businessman, started his first language and computer classes in a small room with a few PCs and a handful of students. His daring venture began to thrive once his reputation peaked. The people who rented him the first floor of a small building ran a café on the ground floor. However, his success did not go unnoticed by his cunning landlords. After witnessing his business flourish, they devised a plan and asked him to vacate the premises.

It was difficult for my brother to leave, as his budding company was associated with this location, and moving would mean losing his business overnight. As Donald Trump aptly states in his bestseller, The Art of the Deal, it is all about "Location, Location, Location," underscoring that real estate prices can vary widely even for similar properties. The same holds true for other businesses.

He tried to negotiate with the landlords, offering to pay higher rent, but they would not budge—they wanted to expand their café to the second floor. With no other option, my brother had to leave and start anew, attracting clients from scratch. It was an uphill battle at the time, but he eventually grew his business, specialising in computers, real estate, and machinery.

It felt like adding insult to injury—when after a few months, the restaurant owners upstairs started the very same business my brother was doing. More regrettable was their venture failed to take off due to their lack of familiarity with the business. They had evicted my brother, who was running a successful business, for no good reason.

Another business model replicated by numerous shops in the Ayat area is liquor shops. This model also surprises me because there is so much competition in the neighbourhood. Despite the competition, some businesses thrive.

In contrast, boutiques selling clothing and footwear benefit from being located near each other, allowing customers to easily compare options and ensuring a steady flow of buyers. This clustering strategy also applies to shops selling building materials, electronics, and furniture, where having multiple options in one area is advantageous for both buyers and sellers.

I believe most businesses in the city tend to be imitators, focusing on familiar sectors rather than innovating. The concept of a business plan is foreign foremost, leading to stagnation, while only a few imitators manage to survive the challenges of the business world. For innovation to flourish, young people need to be encouraged to create new businesses, embracing risk and reaping the rewards. Entrepreneurship involves setting up a business—quite different from the status quo of risk avoidance and reliance on already saturated sectors.

I recall when "The Apprentice," a show hosted by Donald Trump, featured young entrepreneurs competing for mentorship and funding. It was a model for nurturing entrepreneurship, although it frequently ended on a harsh note with Trump's signature phrase, "You're Fired!" echoing in the boardroom. A similar show aired locally, where young people competed for seed capital with various startup ideas. This shows promise that one day real entrepreneurs will flourish.

The state-owned Entrepreneurship Development Institute (EDI), under the Ministry of Labour & Skills, plans to nurture grassroots entrepreneurship among youth and women, in collaboration with global organisations like the UNDP and the World Bank. If progress continues in the right direction, we may see diverse, innovative solutions that grow into big businesses while addressing societal problems.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 01,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1270]

Sponsored Contents | May 02,2023

Radar | Oct 26,2025

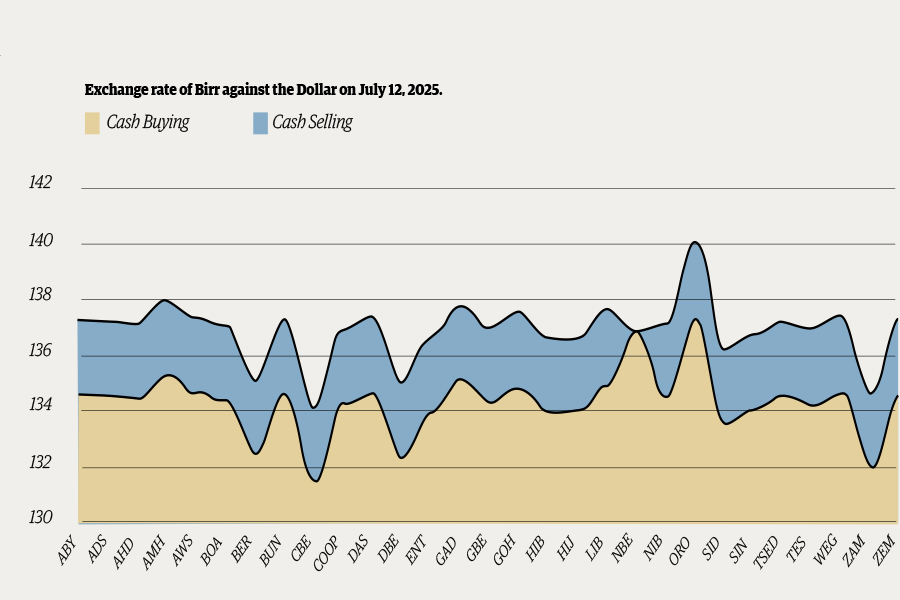

Money Market Watch | Jul 13,2025

Radar | Aug 13,2022

Radar | Oct 18,2025

In-Picture | Jul 14,2025

Radar | Jul 17,2022

Radar | Jun 07,2025

Year In Review | Jan 02,2024

Commentaries | May 31,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...