I have a German friend who is my age. She lived in Addis Abeba in the early years of the Ethiopian revolution with her family, the 1970s. Thanks to her family’s enthusiasm for literature and art, she had a chance to meet with some of the day’s prominent painters and writers. Among them was Dagnachew Worku. She has a copy of one of his books as a souvenir, as a gift from the writer himself. It was the fruit of being acquainted with him in those feverish days.

She knew him long after copies of his epic book “Adefris” were collected from book stores by himself and piled up in one of the rooms of his house. It was so because there was no way he could resist the concerted campaign of the potboilers of the day on the daily papers to criticise his work.

Sure, there were some concerns about the choice of his words in his writing, which makes his book difficult to read without an Amharic dictionary – hardly available then and if even available also hard to refer just for the meaning of a word – close by at hand.

Yet, the man who pioneered creative writing, with a promise of so much more to offer, refused to duel with his many rivals' ill-natured comments. Consequently, he distanced himself from the literary scene. It was unfortunate for Ethiopia’s thriving literary world of the time and the potential it had.

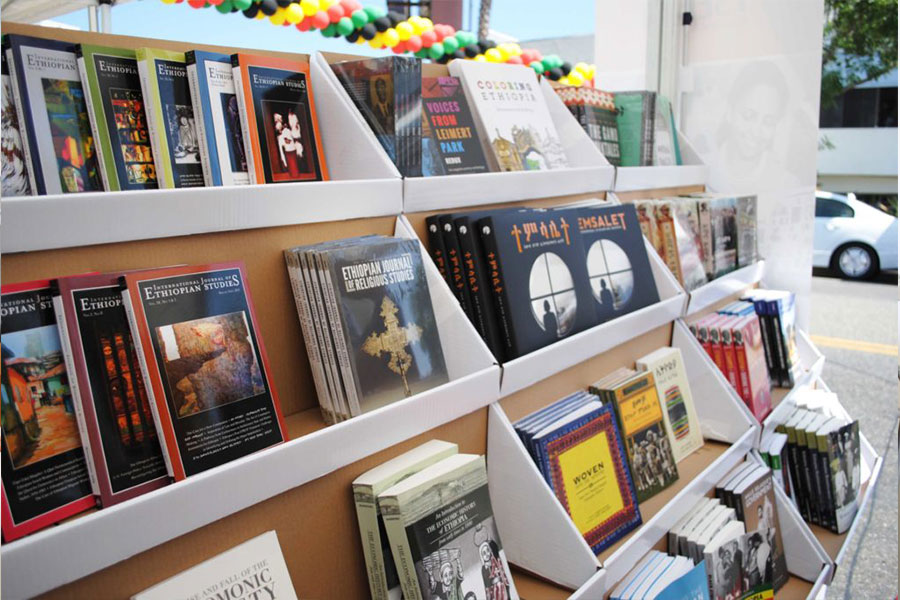

I was reminiscing about this as I was packing some of his books from my collections to donate to Zagol book bank. This was after watching the commendable bank’s effort to nurture the culture of reading in the country, which I learned about from a promotion available on a YouTube channel. It distributes the collections to book clubs established all over the country. It is inspiring that such initiatives exist, giving the literary scene a fighting chance.

A similar effort is Walya Bookstore’s invitation of household name writers to face their audience, breathing further life to their stories as they shed light on what they may have behind the stories. It is equally fascinating to watch that many youngsters gather to have a closer look at their writing heroes, bringing amazing details as conversation openers as questions. They sometimes make ironic comments on books and at times come up with sweeping remarks about writing in the country in general.

There are also the likes of Teraki podcast app, which make publicly accessible audiobooks over their platforms.

It is interesting to witness by following the literary scene closely that writing a book in Ethiopia is never a full-time endeavour. As writers engage themselves in other works for a living, time for research on a given story is rarely available, which definitely has been impacting writing. Initiatives such as the book bank, wh ich I will definitely be a part of, is instrumental in promoting reading and creating an industry and ecosystem that allows writers to thrive as a career.

This is not to mention that a book is written to be read and what good reason is there to remain a bibliotaph, someone who hoards books, keeping them under lock and key? Would it not instead be enriching to be a cause for the next generation of bibliobibuli, the book worms?

Books are prized for what is in them and the work that goes into it and the effort shown by Walya and Zagol promotes reading. Hopefully, this translates to incentivising writing everything worth being on paper, broadening interpretive thinking in our society and discouraging superfluousness.

This helps the next Dagnachew to have our eyes early and give us all one is capable to offer.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 23,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1121]

Sunday with Eden | Jul 24,2021

Radar | May 16,2020

Fortune News | Jan 09,2021

Radar | Mar 06,2021

Featured | Jan 05,2020

Featured | Jan 05,2020

Radar | Jun 19,2021

View From Arada | Jul 09,2022

Fortune News | Jun 14,2020

Radar | Sep 02,2023

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...