For over a week now, social media platforms have been flooded by posts and news about the protests taking place across the United States. Sparked by the death of George Floyd, an unarmed African American male killed in police custody on May 25, 2020, protests and riots have raged across the US amid the nationwide Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and curfews in some cities.

The nationwide protests are no longer contained within the United States. Global outrage has grown in the last few days with anti-racism and anti-police brutality protests taking place across Europe. On Tuesday, the streets of Paris were marred with tension as thousands of protesters took to the streets and clashed with police.

Watching images of people bearing “Black Lives Matter” signs during these protests, it is hard not to contextualise from the perspective of the de facto political capital of Africa what this movement means for those of us living here.

Last week, from Addis Abeba, Moussa Faki Mahamat, chairperson of the African Union (AU) Commission, released a letter strongly condemning the death of George Floyd, which he described as an act of murder.

In his statement, he reiterated a resolution adopted in 1964 by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the AU, which rejects “the continuing discriminatory practices against black citizens of the United States of America.”

The chairperson’s statement was echoed by other African officials such as the President of Ghana, Nana Akufo-Addo.

For over a week now, social media platforms have been flooded by posts and news about the protests taking place across the United States.

“Black people, the world over, are shocked and distraught” by Floyd's killing, said the President in his Facebook post.

The long history of racism against black people in the United States is in no way limited to African Americans but also includes people of colour.

Back in 1999, Amadou Diallo, a 23-year-old Guinean immigrant, was shot and killed by four police officers in New York City. Diallo, who was supposedly mistaken for a serial rapist, was shot at 41 times and was killed after 19 of those bullets struck him. Wrongfully killed and a victim of police brutality, Diallo’s case was a reminder that whether Guinean or African American, black people in the US were subjects of systemic racism.

Do Ethiopians understand what their country signifies and continues to mean to black identity and black nationalism?

Ethiopia, serving as the headquarters of the AU, is one of only two non-colonised nations in Africa. The country was a source of black pride and Pan-Africanism for those living under colonial and white subjugation. It is not a matter of coincidence that many African nations, following their decolonisation, adopted national flags with the colours green, yellow and red.

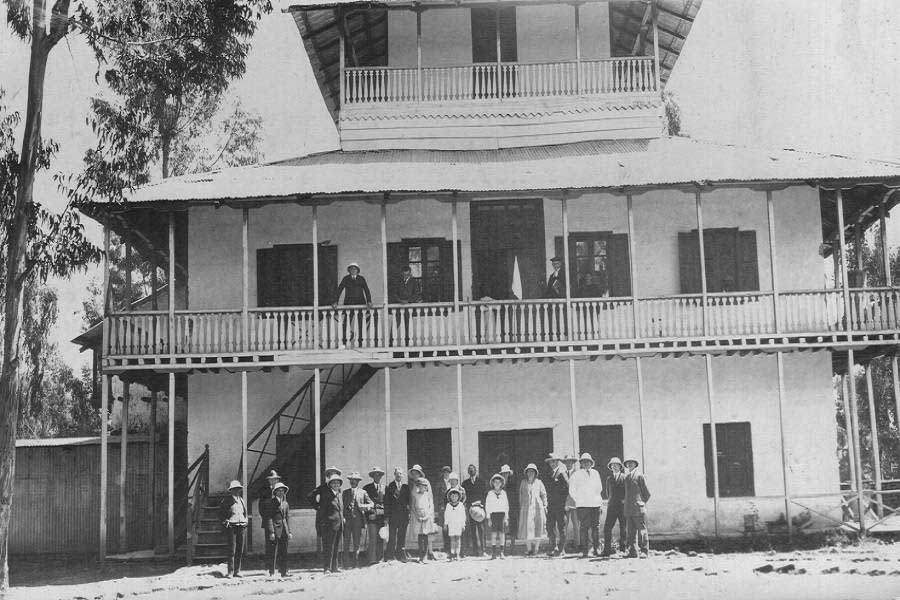

With the exception of the five-year Italian occupation, a consequence of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Ethiopia maintained its independence in the face of colonial conquests. The country served as a beacon of hope, keeping the anti-colonial ideal in the hearts and minds of blacks the world over.

After decolonisation, many African countries and pan-African groups used the Ethiopian colours for the flags of their newly independent nations.

Black nationalism and Ethiopia, however, go beyond the never-colonised rhetoric. It is important to remember and highlight the global black solidarity that took place in support of Ethiopia and Ethiopians during Italy’s second attempt at colonisation.

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War made it so that “common factors of oppression and resistance shaped Ethiopia’s association with Africa or people’s of African descent,” writes Fikru Gebrekidan.

In response to the invasion, African Americans rallied for domestic and international support for Ethiopians. Between 1935 and 1936, newspapers and publications were populated by news of the Italo-Ethiopian war. Unfortunately, there is not much acknowledgement of the African-American involvement during the war.

Across the United States, African-Americans worked immensely to gather assistance for the Ethiopian cause.

“To keep the black public informed on the Italo-Ethiopia issue, the Urban League and especially the [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] NAACP published pro-Ethiopian editorials and articles in the pages of their official publications,” as William Scott, professor at Wellesley College, reminds us in his journal article, “Black Nationalism and the Italo-Ethiopian Conflict.”

Groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) also carried out diplomatic missions in which they pushed, albeit unsuccessfully, what was then the League of Nations to “restrain Italian aggression in Ethiopia.”

For a nation that was seen as the bastion of black power, our relationship with our black identity is at best confusing. Many Ethiopians do not identify as being black. We tend to draw a separation line between our identity as an Ethiopian and our identity as black. At times, that departure, sadly, tends to border on racial arrogance.

Ethiopia’s political complexities make it challenging to now insert black identity in the overarching conversation surrounding identity politics. Furthermore, perhaps it is not the best time to confront the issue. Ethiopia currently has its fair share of domestic and international issues that require the government’s full attention. We may need to pick our battles.

It is absolutely necessary to reflect upon what the current global outcry means to us as a people and as a country, which has stood and continues to be a symbol of freedom and black pride. It is imperative to think about what this situation means to the young diaspora living in the United States today. It is essential to remember that in a racialised world, it does not matter much if one is Ethiopian or African-American. Amadou Diallo was not African-American.

“Our problem is your problem. It is neither a black problem nor a specifically American problem. It is a global problem, a problem that involves all of humanity. It is not a civil rights problem, but a human rights problem,” Malcolm X said during the 1964 OAU conference in Cairo.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 07,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1050]

Fortune News | May 04,2019

Exclusive Interviews | Apr 19,2025

View From Arada | Aug 07,2021

Radar | Nov 02,2019

Covid-19 | May 31,2020

Exclusive Interviews | Dec 12,2020

View From Arada | Apr 16,2022

Fortune News | Oct 25,2025

Featured | Jun 29,2025

Sunday with Eden | Dec 31,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...