Editorial | Oct 30,2022

Apr 1 , 2023.

Teshome Toga, a seasoned public serviceman, now bears the weight of immense responsibility. Having spent years as a diplomat in Kenya, later serving as a Speaker of Parliament, and subsequently returning to diplomacy as an ambassador to France and China, his latest task might be his most challenging. As the head of a delicate political program overseen by the National Rehabilitation Commission, Teshome is tasked with demobilizing and reintegrating nearly a quarter of a million former combatants and soldiers from Ethiopia's seven of the 10 regional states.

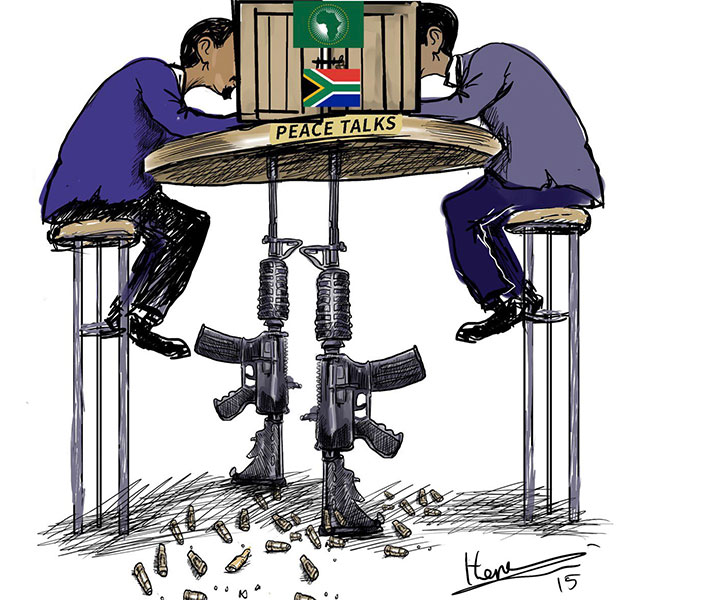

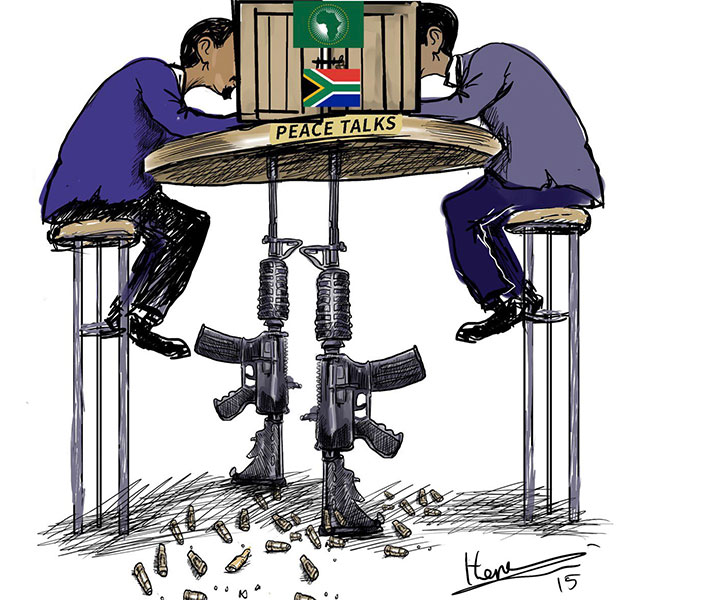

The challenge of reconstruction and addressing the root causes of violence after civil wars is monumental. Central to this challenge is the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of former combatants—a process fraught with contentious issues, potential pitfalls, and questions over responsibilities and successes.

For DDR to succeed, a comprehensive political settlement that addresses the war's root causes and fosters trust among former adversaries is vital. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) provides a cautionary tale of recurring violence and instability in the absence of such a framework. To avoid a similar fate, Teshome and his team, including donors, should prioritize political dialogue and transitional justice alongside DDR initiatives.

Ethiopia recently endured a brutal two-year civil war in Tigray and neighbouring regional states, with the involvement of several foreign actors, primarily Eritrea, complicating the outcome. When Addis Abeba and Meqelle entered into deals in Pretoria and Nairobi to silence the guns, a plethora of post-war issues arose, mainly the disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of combatants.

The federal Parliament legislated the establishment of a national commission to oversee the rehabilitation of affected communities and the reconstruction of war-damaged areas. The crucial task of reintegrating nearly 250,000 former fighters and soldiers carries an estimated cost of 30 billion Br, making it the most expensive DDR program the country has seen.

Ethiopia is no stranger to such programs, with the current initiative being the third in the past 30 years. The first, in the 90s, cost 196 million dollars and demobilized half a million soldiers who had served for 20 years and disabled war veterans. The second, lasting five years until 2005, aided 148,000 soldiers who had fought against Eritrean forces, including 17,000 disabled veterans, at the cost of 174 million dollars, mostly borrowed from the World Bank.

These programs were considered to have reasonable success.

DDR programs are most successful when tailored to each post-conflict context and responsive to the specific needs and characteristics of affected communities, including vulnerable groups like women and children. One-size-fits-all approaches are doomed to fail. The programs should go beyond mere disarmament and demobilization, encompassing psychological, educational, and vocational assistance to facilitate the reintegration of former combatants into society.

Collaboration among regional states, international donors, and non-governmental organizations is crucial for effective DDR processes. Aligning efforts and resources can improve the efficiency and sustainability of such initiatives. However, success requires a long-term commitment and investment to address the complex needs of former combatants and support their transition to civilian life. Colombia, Sierra Leone, and Liberia provide valuable insights into achieving lasting peace and stability following successful DDR processes.

Teshome and his team would benefit from seeking the expertise of individuals like Dawit Weldegiorgis (Major), who has gained extensive knowledge and experience leading UN DDR programs in Liberia and Rwanda. He was a chief of Ethiopia's relief and rehabilitation agency back in the 80s during the height of the "Great Famine". Mulugeta Gebrehiwot's, a.k.a Chaltu, impressive experience in demobilising half a million soldiers in the mid-90s, including his dissertation on Ethiopia's DDR experience, could also prove valuable.

Reading the works of these individuals ascertain that the path to lasting peace is fraught with complications. Policymakers and practitioners must learn from past experiences and incorporate best practices into DDR initiatives. Regular monitoring and evaluation to identify shortcomings and areas for improvement are necessary for successful programs. Policymakers can make evidence-based decisions and allocate resources more effectively by tracking progress and assessing intervention impacts.

Conflicts often have regional dimensions, with armed groups operating across borders or receiving support from neighbouring countries. DDR programs should consider these factors, fostering regional cooperation and collaboration to promote stability and reduce the risk of conflict spillover. Eritrea's role during the war and influence in the post-conflict engagement cannot be ignored; excluding its leaders from the delicate process could undermine Teshome's efforts, though appeasing Asmara may be beyond his remit.

Domestic actors, such as community leaders and grassroots organizations, play a crucial role in the success of Teshome's commission. Empowering them to lead the DDR program from design to implementation will result in more contextually relevant and sustainable initiatives in the long term.

While instrumental in stabilizing post-conflict societies, DDR programs must be complemented by efforts to address the root causes of conflicts, such as political grievances, social inequalities, and resource competition. Policymakers can help prevent the resurgence of violence by addressing these underlying issues and creating a more resilient foundation for peace.

Since the 80s, DDR initiatives have been implemented in post-conflict societies from Angola, DRC, and Uganda to Bosnia, Cambodia, and Nicaragua. However, Liberia's experience is a stark reminder of the failure of DDR programs undertaken without political settlement and accountability for wartime atrocities.

Liberia experienced two brutal civil wars between 1989 and 2003, which claimed the lives of a quarter of a million people and displaced millions more. The international community and the Liberian government embarked on a DDR program to address armed groups and foster national reconciliation following the end of the second civil war in 2003.

Despite initial successes, the program failed to address the root causes of the civil war. It did not engage in inclusive political dialogue or transitional justice mechanisms, leading to the re-emergence of tensions and violence. The exclusion of marginalized communities and the lack of genuine political reforms fueled resentment and mistrust among different factions, undermining the program's long-term effectiveness. The Truth & Reconciliation Commission (TRC), established in 2005, was unable to fulfil its mandate, and the absence of a robust transitional justice process impeded the successful implementation of the program.

The failure of the DDR process in post-conflict Liberia highlights the necessity of addressing the root causes of civil wars through political settlements and transitional justice mechanisms. Ignoring these crucial components can re-emerge tensions and violence, threatening the prospects for lasting peace and stability. It would be tragic for Ethiopia to require a fourth DDR program; Teshome and his team must do it right this time around.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 01,2023 [ VOL

23 , NO

1196]

Editorial | Oct 30,2022

Fortune News | Dec 26,2020

Advertorials | Mar 06,2023

Radar | Dec 01,2024

View From Arada | Mar 20,2021

Viewpoints | Mar 26,2022

In-Picture | Sep 29,2024

Fortune News | Apr 06,2019

Commentaries | Dec 11,2021

Featured | Sep 04,2021

Photo Gallery | 179903 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170099 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161083 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137228 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 2 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has scrapped the credit-growth ceiling that had s...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

The burgeoning data mining industry is struggling with mounting concerns following th...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Berhan Bank has chosen a different route in its pursuit of a new headquarters, opting for a transitional building instea...

Nov 2 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Nib International Bank S.C. has found itself at the epicentre of a severe governance...