Fortune News | Aug 21,2023

May 31 , 2025

By Kaushik Basu

In mainstream economics, description is routinely treated as secondary to analysis. Labelling a work as "purely descriptive" conveys dismissiveness. Yet, as Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen observed in a seminal 1980 paper, every act of description involves choices. Whether we are describing a historical event, an individual, or a country, what we choose to include and what we leave out can be critical.

Description shapes perception, and perception, in turn, can profoundly influence behaviour. Describing the state of a country's economy is a complicated task. In the past, scholars wrote lengthy volumes debating whether one country was doing better than another. But over time, a single measure has come to dominate the conversation. Gross domestic product (GDP) represents the value of all goods and services produced within a country in a given year.

With some adjustments, it also approximates the population's total income. It is an astonishingly concise metric, often used as shorthand for economic well-being.

As Diane Coyle noted in her 2014 book on the history of GDP, its emergence marked a watershed moment in economic policymaking. Developed by Simon Kuznets in the early 1930s, GDP has brought much-needed rigour to policy debates. Politicians could no longer simply point to tall buildings as evidence of progress (though many still do). Today, assessing a country's economic performance over time means tracking the growth of its GDP.

To be sure, there are other ways to assess national well-being, such as the United Nations' Human Development Index and the World Bank's Shared Prosperity Indicator. But, when it comes to determining whether one economy is outperforming another, GDP (or GDP per capita) remains the default benchmark.

While GDP has undoubtedly played a valuable role in modern economics, its limitations are increasingly difficult to ignore. Over time, it has become an end in itself, enabling politicians to use growth figures as a convenient distraction from persistent social and economic fractures. Growing unease with GDP-centric policy thinking was powerfully articulated in UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterees's 2021 report "Our Common Agenda", which urged global policymakers to embrace a broader set of progress indicators.

As an economic indicator, GDP has three key weaknesses.

By focusing solely on a country's total income, it can create the illusion of widespread prosperity, even when inequality is rising. GDP per capita can rise even as a majority becomes worse off. As Joseph E. Stiglitz put it in his 2010 book "Freefall", "A larger pie does not mean everyone – or even most people – gets a larger slice." But most people may celebrate GDP growth nonetheless, much like they cheer their country's Olympic medal count, without questioning who actually benefits.

This concern was highlighted by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance & Social Progress, which was established in 2008 by then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy and included Stiglitz, Sen, and other prominent economists. Its final report called for incorporating measures such as income distribution and inequality into the GDP.

The other weakness of GDP is that its maximisation often rewards activities that undermine democratic governance. Being super-rich, after all, involves more than simply owning more cars, mansions, planes, and yachts. Extreme wealth, especially in the age of social media and AI, also means having a louder voice and disproportionate influence over how people think.

In traditional societies, when a feudal lord entered a village council meeting, ordinary people who may have been arguing and pleading for change moments earlier would fall silent. That same dynamic is now playing out on a global scale. As wealth becomes concentrated in fewer hands, and as a handful of online platforms shape what billions of internet users see and hear, many are discovering that they are losing their voice, the most essential instrument of democracy.

Clearly, the time has come to develop new measures of national progress that do not strengthen the forces threatening democracy. As US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously warned, "We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both."

Lastly, GDP can be inflated at the expense of future generations. We can and do boost GDP growth by engaging in activities that damage the environment and accelerate climate change, leaving our descendants with a scorched earth.

Given this, merely acknowledging the urgency of climate action is no longer enough. To ensure a sustainable future, we should reform our most prominent measure of economic welfare so that sustainability is central to how we define prosperity.

PUBLISHED ON

May 31,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1309]

Fortune News | Aug 21,2023

Fortune News | Sep 09,2024

Fortune News | Sep 01,2024

Sponsored Contents | Aug 22,2022

Radar | Jul 17,2022

Fortune News | Nov 09,2024

Radar | Dec 29,2018

Commentaries | Mar 19,2022

Agenda | Aug 23,2025

My Opinion | Sep 21,2019

Photo Gallery | 177180 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 167391 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 158014 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136963 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

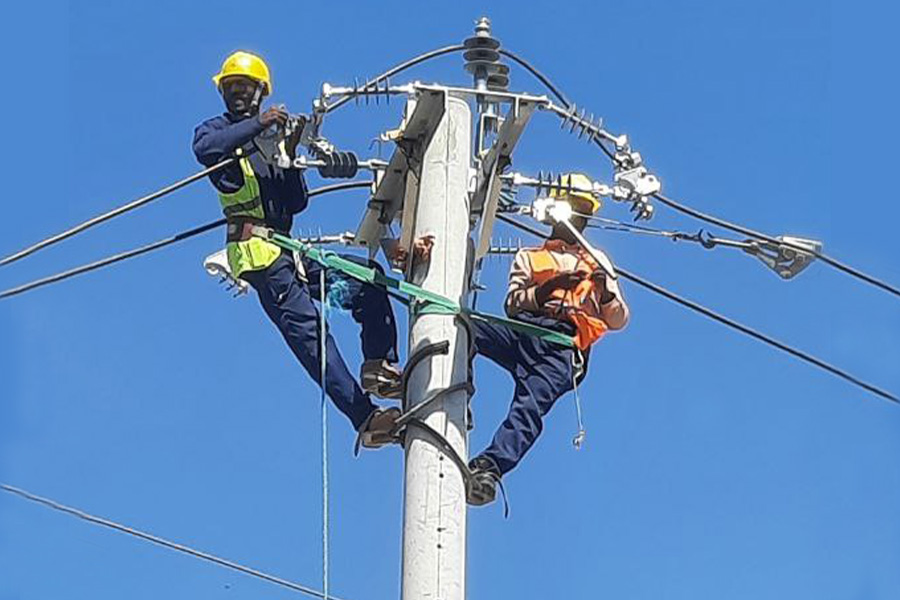

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

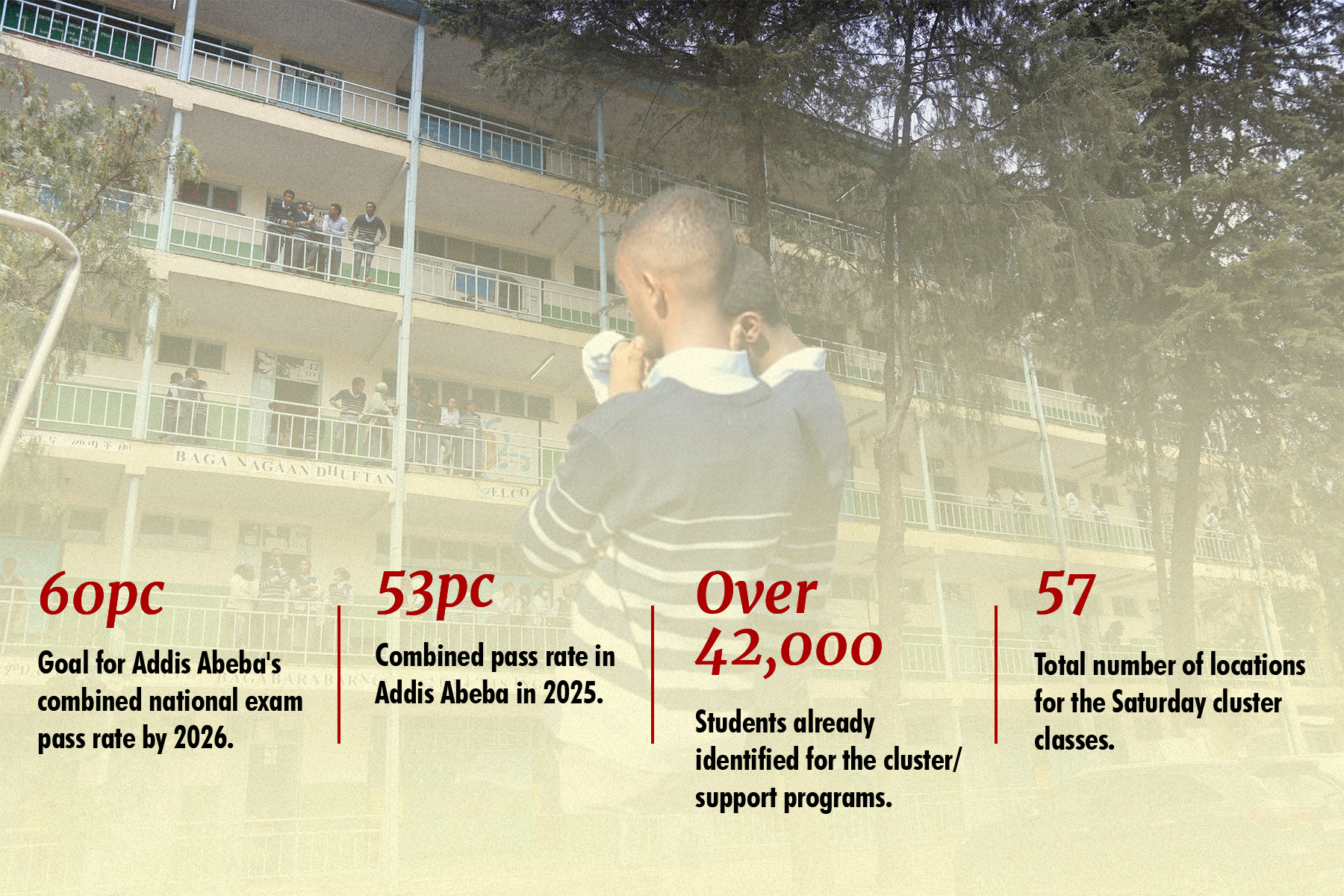

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...