In-Picture | Aug 11,2024

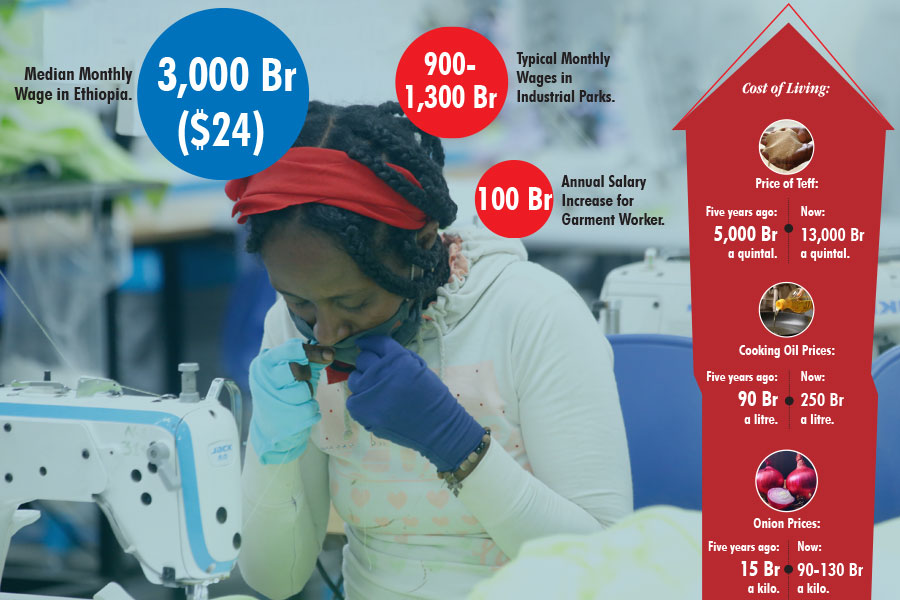

The quest for better livelihoods has driven hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians to venture to the Middle East in hopes of better jobs. However, their journeys are often marred with abuse, maltreatment, and exploitation. Despite the hardships faced by Ethiopians abroad, the drive to migrate persists, fuelled by economic hardship and hope for a better life. While measures are being taken to regulate and improve conditions, undocumented migration remains pervasive. Reports suggest that only 40pc of Ethiopian migrants possess legal documents.

A returnee, Sara Markos now works at “Egna-Legna”, a non-profit offering skills training for returning women like her. A reflection of many such stories, Sara’s tells the plight of the 132,000 immigrants that have made the reverse journey in the past two years. A 2017 study by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) highlighted the pernicious conditions most Ethiopian migrant workers endure, particularly those ensnared by the “Kafala” sponsorship system—a framework used in Gulf countries to manage migrant workers. The system amplifies their vulnerability, leading to forced labour, withheld salaries, passport confiscations, and restricted rights to negotiate wages or switch employers. Migrant workers suffer from health problems, exacerbated by their limited access to medical care.

Federal authorities claim to have been trying to aid stranded migrants, with programmes to ensure the migrants' reintegration into society. They speak of plans to extend support to repatriating migrants to other African countries. Yet, the drive for foreign earnings continues, with an agreement between Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia set to send a fresh wave of "trained workers" to the Middle East. The focus has been on equipping women, the primary demographic seeking employment as housemaids, with basic skills and certifications. However, this has not been devoid of criticism. While it provides a respite for the foreign exchange-strapped Ethiopia, remittance income, experts argue, is a short-term solution often used for consumption rather than investment. As Tadele Ferede, former president of the Ethiopian Economics Association, put it, remittance is a "pain killer, not a cure". Experts argue the focus should shift to boosting agriculture, manufacturing, and domestic investments.

You can read the full story here

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 29,2023 [ VOL

24 , NO

1213]

In-Picture | Aug 11,2024

Letter To Editor | Aug 19,2024

Sunday with Eden | Jun 01,2024

Editorial | Jul 29,2023

In-Picture | Apr 19,2025

My Opinion | Apr 03,2021

Fortune News | Dec 15,2024

Fortune News | Aug 18,2024

Fortune News | May 04,2024

Fortune News | Sep 07,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...