View From Arada | Sep 06,2020

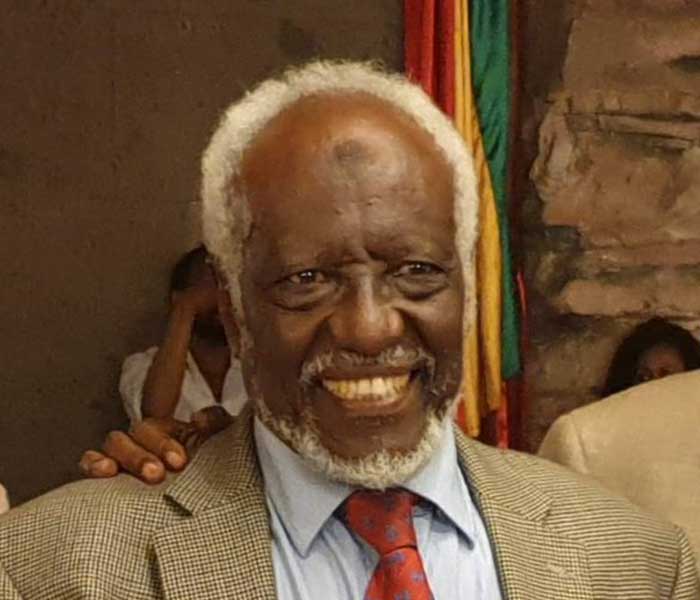

The former Relief & Rehabilitation Commission was an island of sanity in the sea of pandemonium that was Communist-era Ethiopia. Exemplifying this contrast was Teferi Asfaw, who found himself working at the Commission after answering a recruitment call in the mid-1970s.

“Understanding the background is necessary to understand Teferi,” said Girma Kassa, his colleague at the Commission. “It was a time when officials regularly carried weapons when they went to work.”

Teferi, who passed away on July 27, 2020, after a sudden respiratory arrest, and his colleagues were not the gun-carrying type. But they had to contend with a Marxist-Leninist military junta, the Dergue, that was trying to save face while around 100 lives were being lost a day. The time was the early 1980s, and Ethiopia was making a name for itself as the poster-child of famine and hunger.

The Commission had to somehow get around the fact that the military junta was not just incompetent but had also allied itself with the losing side of the Cold War.

The Soviets were competitive with the West in terms of military muscle and even industrial output. Agriculture, on the other hand, was another story. Embarrassingly enough, the Soviets were themselves importing grain from the United States on several occasions. There was little they could do for food starved Ethiopia.

“They once gave us thousands of tonnes of salt in aid,” said Girma.

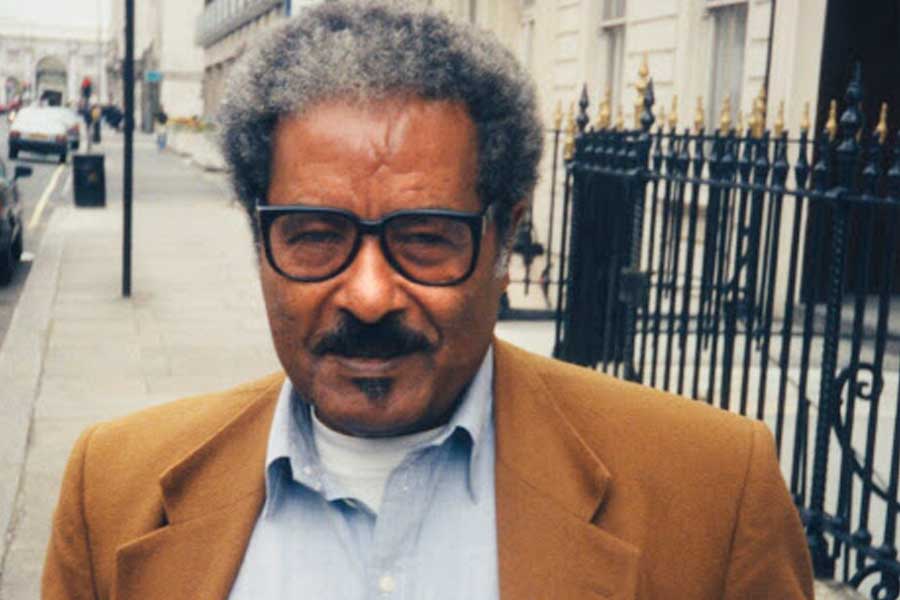

This did not fly with Dawit Woldegiorgis, then head of the Commission, who sent Teferi and his colleagues to the department of the ruling Worker’s Party that was in charge of “ideology,” to explain that the country cannot accept this. Starving people needed food not seasoning. Even if they were to monetise it and then buy the food, many people would starve to death before the humanitarian aid reached them. Time was of the essence.

They would implore, supplicate and beg, always with apprehension - unsure of just what would tick off the military guys. There were times when they would have to wait for an hour – without even an invitation to sit – outside the office of some higher-level cadre. All of this merely because the Party could not be bothered to refuse its ideological ally barely useful aid.

Teferi, who had grown up in a middle-class family and was roughly introduced to the inequities of hunger and deprivation, was on the front line of the fight as a logistics information officer. They were trying to save lives. The regime was convinced that the Commission was out to give them a bad name.

In the end, Teferi would lose this fight, and Ethiopia accepted the refined salt, which was then sold in the market. It was later found that it was past its expiration date.

Teferi was lucid under such abysmal circumstances. He maintained a composure that earned him the name “shock observer.” There were threats to his and his colleagues' lives, perhaps not uttered directly but implicitly. Teferi himself was locked up several months not long after the Dergue took power. They would get calls from Legesse Asfaw, one of the most senior officials of the military junta, and visits at their headquarters from Mengistu Hailemariam, Ethiopia’s ruler until 1991.

“They didn't trust us,” said Girma, who worked at the Commission with Teferi. “Still Teferi was never afraid. He remained calm and collected.”

It is not like he did not have much to worry about. The oldest child, born to a family that made its income in the coffee trade, he had to shoulder familial responsibilities when he was 17 years old after the death of his father. His siblings called him Gashie.

“[He was] a devoted professional who was born rich but worked harder than the poor,” said his siblings, writing jointly about Teferi who is survived by his wife and son.

There was much to juggle during his time as an undergraduate at Adds Abeba University, then Haile Selassie I University. He left school without finishing.

“He was unlike most other students – mature and careful,” said Shibeshi Lema, colleague and friend, who was a housemaster at the University.

It was after leaving school that he would begin a decades-long excursion into public service. His first stint was at the Ethiopian Statistical Authority, but he soon left to serve as disaster management supervisor in what was then known as Wollo Province in the northern part of the country. It was during that time he ran afoul of the authorities and was sent to jail.

He came back to Addis Abeba in the late 1970s to work at the headquarters of the Commission, where he would stay for over a quarter of a century serving under various titles. He would get reacquainted here with his housemaster from the University, Shibeshi, and remain colleagues with him even after joining the Addis Abeba Chamber of Commerce & Sectoral Association.

It was Shibeshi who, as a senior, vouched for Teferi when he asked permission from the Commission to go back to school and finish his bachelor’s degree in foreign language and literature.

“He didn't make me regret it one bit,” said Shibeshi. “He went to school during the day but did not skimp on his duties at the Commission.”

Decades later, after Teferi had joined the City Chamber upon Shibeshi’s recommendation, who was already working there, the language major and longtime public servant would rise through the ranks and become deputy secretary-general.

Shibeshi pulled Teferi to the side soon after his promotion and reminded him of what a good boss he was to him and for the thoughtfulness to be reciprocated now that the tables had turned.

“It’s going to be performance-based,” quipped Teferi. “As long as you perform well, you'll be fine.”

He left the Chamber in the early 2010s when he reached retirement age. It was a healthier environment but not without its challenges.

Soon after he was hired there as head of public relations, he organised Miret Addis, a discussion platform for contending political parties and individuals during the 2000 general election. He hoped that candidates would discuss policy recommendations relevant to the business community.

The authorities were suspicious. They asked what Addiswas supposed to reference, which meant "new" in English.

Was Miret Addis intended to mean “choose new?" Choose anyone but the incumbents?

Teferi kept a straight face when he insisted that “Addis” was a reference to the Chamber.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 08,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1058]

View From Arada | Sep 06,2020

Featured | Oct 27,2024

Obituary | Mar 14,2020

Radar | Dec 08,2024

Fortune News | Oct 15,2022

Obituary | Oct 17,2020

Fortune News | Feb 05,2022

Obituary | Oct 11,2020

Fortune News | Nov 14,2020

Obituary | Nov 29,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...