Fortune News | Nov 14,2019

Sep 27 , 2025

By Gabriel Mekbib

A decade ago, Addis Abeba hosted a United Nations summit that brought together world leaders, finance ministers, and development experts. The resulting “Addis Abeba Action Agenda” sought to move global investment for development from “billions to trillions.” Nonetheless, for many, the funds never arrived as hoped, writes Gabriel Mekbib (gabriel@projectstarling.org), who worked for over a decade with international development and policy organisations, such as UNESCO, covering Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, and Zambia, before joining Project Starling.

Ten years ago, Ethiopia hosted a major United Nations conference on financing for development, with global leaders gathering in Addis Abeba to sign what became known as the "Addis Abeba Action Agenda." At the time, the agreement was viewed as a milestone, with many hoping it would attract substantial private investment and help countries achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The talk focused on unlocking a flow of money, moving from “billions to trillions,” particularly for countries in the Global South.

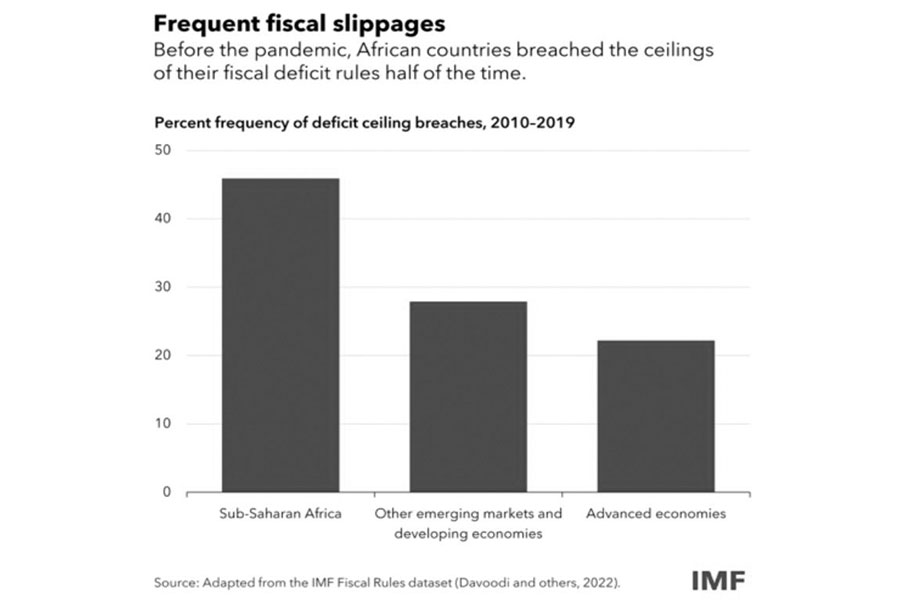

But a decade later, the results have been mixed. The Addis Abeba agreement did not set off the expected wave of private capital. As the Global Policy Forum has pointed out, the agreement did achieve some progress, particularly in encouraging countries to focus on international tax cooperation and raising more revenue domestically. Still, for many African countries, including Ethiopia, the core problems of financing development persist.

Ethiopia’s own experience has mirrored these challenges, with the country facing a steep 30pc currency devaluation in July 2024 and heavy debt repayments, both of which have become familiar stories across the continent.

It was with a mix of urgency and scepticism that African leaders approached the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, which took place in Seville, Spain, from June 30 to July 3, 2025. Out of that meeting came a new agreement, known as the Compromiso de Sevilla, or the Seville Commitment. Kenya’s President William Ruto described it as “a renewed, if not hard-won, commitment to multilateralism and equitable development.”

The question now is what new tools African countries can use, based on the outcome document of Seville and its related Platform for Action, to improve their financial situation.

One of the biggest worries for African governments is the debt trap. In more than half of Africa’s countries, the cost of repaying debts is now greater than the amount spent on healthcare, according to calculations by the ONE Campaign, which used data from the World Bank, UNESCO, WHO, and IMF. Botswana’s Vice-President, Ndaba Gaolathe, called it “not just a debt crisis; it is a justice crisis.” The Seville agreement tries to address this problem in several ways.

First, it establishes a United Nations-led process to shift debt talks away from closed groups, such as the Paris Club, and into more inclusive UN forums. It also launches a Borrowers’ Forum under the United Nations Conference on Trade & Development (UNCTAD), which is meant to help countries negotiate together rather than separately. A Global Debt Registry, managed by the World Bank, will consolidate debt information from various sources to enhance transparency and accountability. The Platform for Action features a Global Hub for Debt Swaps for Development, backed by Spain with a three-million-euro investment, as well as a provision that enables countries to temporarily suspend debt payments during crises.

These steps may help resolve an old issue of creditors usually coordinating closely, while debtor countries are left to bargain alone.

The new Borrowers’ Forum could help African governments share ideas and strengthen their negotiating power. However, for many in Africa, these measures are insufficient. The Seville agreement fell short of establishing a legally binding process for debt relief, a goal many countries sought, particularly following the African Union (AU) Conference on Debt in May 2025.And while the agreement calls for increasing developing countries’ voting power in international financial institutions, this goal faces likely resistance from the current United States administration, which was not a signatory.

Central African Republic's Finance Minister, Hervé Ndoba, underlined the issue when he said, “Africa, with its 1.5 billion residents, has the same voting rights as countries of fewer than 100 million.”

Another key issue is how credit rating agencies judge African economies. Many African leaders argue that these agencies, which include Moody’s and S&P, often exaggerate the risks of investing in Africa, which makes borrowing more expensive. Sierra Leone’s Chief Minister, David Moinina Sengeh, said that current ratings “frequently fail to reflect our reform trajectories.”

The AU has backed a homegrown alternative, the African Credit Rating Agency (ACRA), but the Seville Commitment goes further by creating annual meetings between countries, rating agencies, and regulators. The goal is to promote greater transparency in the rating decision process, require agencies to clearly explain their criteria, and ensure that progress on reforms is taken into account. While this does not solve the problem overnight, it gives African governments a seat at the table and an opportunity to demand greater accountability.

At the same time, Seville reaffirmed the need for countries to strengthen their own finances by boosting domestic revenue. Many African countries lose funds to illicit financial flows, which are money that is illegally transferred out of the continent. Nigeria’s Foreign Minister, Yusuf Tuggar, noted, “Illicit financial flows drain Africa of 88.6 billion dollars every year,” matching the total amount of official aid Africa receives, according to UNCTAD estimates.

The Compromiso de Sevilla includes a promise to double support for domestic resource mobilisation by 2030, with practical steps like improving e-filing systems, expanding the value-added tax, and modernising customs. It also maintains momentum behind the idea of a United Nations Tax Convention to combat tax avoidance by international companies. A new coalition has also been launched in Seville, with countries such as Kenya, Somalia, Benin, and Sierra Leone endorsing a plan to raise money by imposing a levy on premium air travel, with the proceeds to be used for combating climate change.

However, some gaps remain. Despite its potential to raise Africa’s GDP by USD 450 billion by 2035, the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (ACFTA) was not mentioned in the Seville document, missing an opportunity to connect a crucial African policy with global financing efforts.

Still, the Seville meeting introduced some new tools, including the Borrowers’ Forum, meetings with rating agencies, and more substantial support for generating additional revenue at home. These address real challenges, fragmented debtor groups, unclear credit ratings, and weak government finances, even if they fall short of more sweeping change. As Sierra Leone’s Vice-President, Mohamed Juldeh Jalloh, said, the real goal is to “shift the conversation from dependence to dignity.”

After a decade of big promises and slow progress, the challenge is to turn these new agreements into tangible results.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 27,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1326]

Fortune News | Nov 14,2019

My Opinion | Jul 25,2020

Radar | Apr 24,2021

Agenda | Nov 04,2023

Sunday with Eden | Oct 31,2020

Commentaries | Sep 07,2019

Radar | Sep 18,2022

Commentaries | Feb 06,2021

Radar | Feb 01,2020

Commentaries | Sep 30,2023

Photo Gallery | 175937 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 166152 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 156564 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136853 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

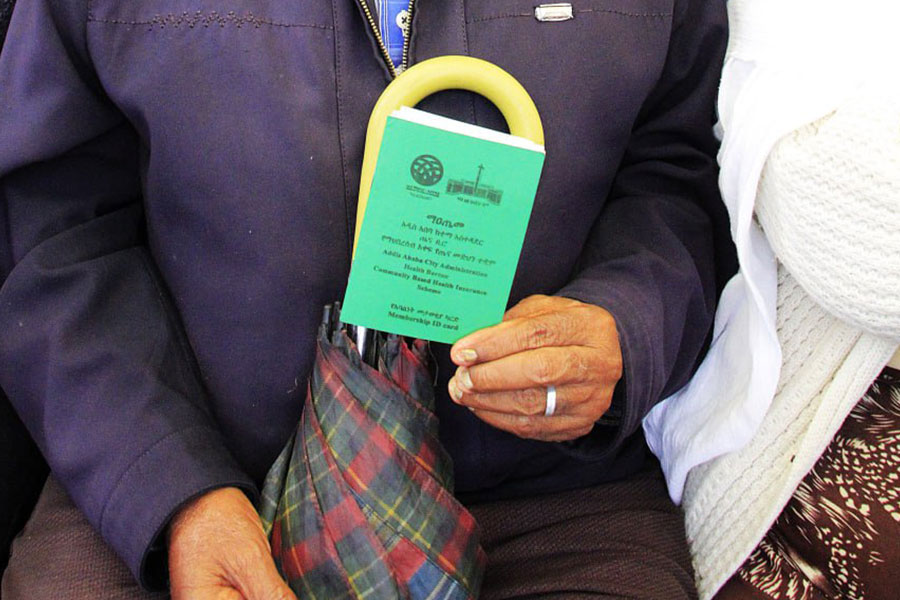

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...