Commentaries | Jan 26,2019

Federal education officials have issued a stern warning to private colleges, where a large number of institutions are at risk of losing their permits if they fail to meet tough new standards introduced under a 2024 Licensing Re-Registration Directive.

Imposing a tight deadline, officials of the federal Education & Training Authority (ETA) have given colleges six months to comply or face closure.

The crackdown, announced at a press briefing last week at the Ministry of Education, up at Arat Kilo, comes after growing concerns over the quality and regulation of private higher education. According to Hiwot Assefa, CEO of Higher Education Licensing at ETA, the directive was designed to establish a uniform licensing system and ensure that authorities have accurate data on institutions operating in the sector.

The new directive represents a major shift for colleges that, for years, have operated with relatively loose oversight. The changes require private universities to own or rent entire buildings dedicated solely to education. Henceforth, they will no longer be permitted to share facilities with other businesses. Institutions are also required to employ doctoral holders as instructors and administrators, and they should deliver tangible results; at least one-third of students need to pass the national exit exam.

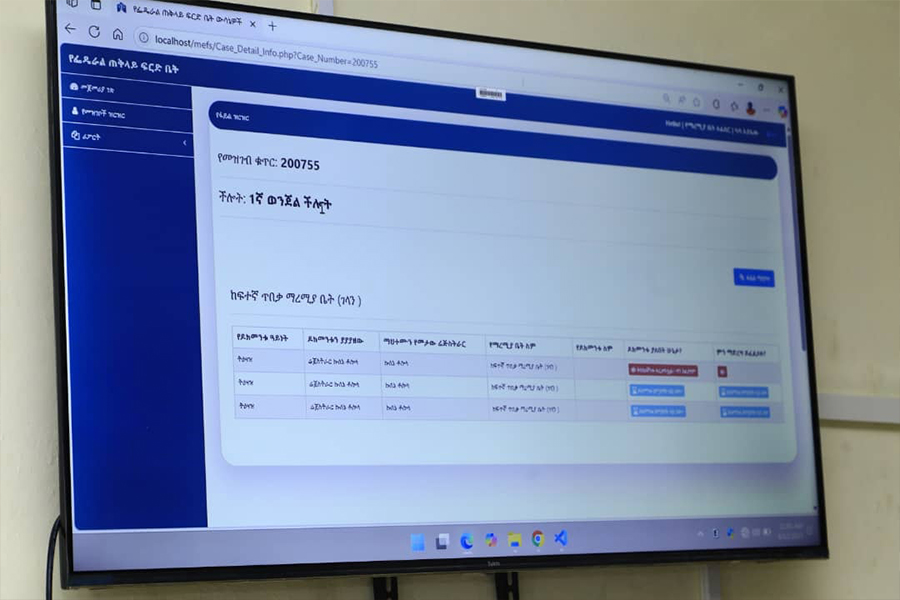

Of the 375 private institutions expected to re-register nationwide, only 290 submitted applications last year, while 85 chose to withdraw from the process altogether, transferring their students to other institutions. In the capital, 75 institutions, 112 campuses, and 556 programs have successfully met the first registration requirement. However, the results of field inspections proved disappointing for regulators. After three rounds of assessments, only three institutions, three campuses, and 17 academic programs were found to meet all the requirements for full accreditation.

"The first round of field evaluation yielded shocking results," Hiwot told reporters. "Many institutions failed to meet even the minimum requirements.”

Consequently, 25 institutions that had made partial progress were granted a one-year grace period to address shortcomings. Another 62 institutions received a six-month extension, but with the caution that non-compliance would result in the loss of their licenses.

Private colleges have pushed back, voicing alarm over what they say are unrealistic deadlines and impractical requirements. According to Tefera Gebeyehu, general manager of the Ethiopian Private Higher Education Institutions Association (EPHEIA), the standards were simply unattainable within the provided time frames. He could find it difficult to see the feasibility of colleges offering health programs, building their own hospitals, which is now a requirement, within a year.

“The directive is unachievable,” he argued. “Some rules do not directly improve teaching quality yet remain mandatory.”

Tefera also criticised the process for its lack of consultation, urging education authorities to reconsider some of the tougher requirements.

But education officials have refused to back down. Minister of Education Berhanu Nega (Prof.) insisted that quality, not protecting underperforming institutions, was his government’s main concern. He claimed that the Ministry had consulted with private schools over the past three years, and those that failed to improve should not expect to stay open.

“From now on, it will not be possible to set up something on a rented floor and call it a college,” he said. “Ethiopia cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past three decades.”

The Minister also dismissed fears that the closures could trigger a national crisis.

“Our concern is that students shouldn't be awarded degrees without receiving proper education,” he said.

The stricter requirements have triggered worries among college leaders, who say the reforms could drive some institutions out of business and limit access to higher education for students in Addis Abeba, where demand is high. Zelealem Belay, representing Yared Industrial, Technology & Business College, found the deadlines too short for most colleges to realistically comply.

“By setting standards that cannot be met, are we not depriving students of the opportunity to learn?” he asked.

Despite pledges by the Minister that public universities would also be held to the same standards and face closure if they failed to comply, for some, the changes seem to set the bar higher than even they can reach.

Samson Zerihun of Zemen Postgraduate College acknowledged the need for re-registration but questioned the practicality of some rules. He is worried that a dean’s office, required to be between 20Sqm and 40Sqm would force many colleges to construct entirely new facilities. He also attributed the challenge of recruiting enough full-time PhD instructors to the small number of qualified professionals in Ethiopia and the reluctance among academics to accept full-time contracts.

Unity University President Arega Yirdaw (PhD) noted another difficult provision. The rule requires that instructors who have been working overseas must be accredited, Arega believes some have found the process difficult.

“This isn't something that can be achieved in one year or even six months,” he said, calling on regulators to be more realistic.

At ETA, officials have responded by defending the new rules and the speed at which they are being applied.

Ahmed Abtew (PhD), the authority’s director general, echoed the Education Minister’s position. He warned that, unlike colleges given one-year extensions, those with six-month deadlines posed more serious risks to quality.

“Let’s change what needs to be changed," Ahmed said. "If it doesn’t work, we'll redirect resources to another sector.”

Woubshet Tadele, ETA’s deputy director general in charge of licensing and quality audit, argued that many requirements had already been relaxed to reduce the burden on colleges. He claimed most standards could be met within six months to a year if schools were serious about making changes, though he left the door open for additional time in special cases. Addressing concerns about the shortage of PhD instructors, Woubshet said schools should either support current staff in obtaining advanced degrees or suspend programs that lack qualified faculty.

“If there are no teachers, there should be no program,” he said. “Standards cannot be compromised.”

This is a voice amplified by Alemayehu Teklemariam (Prof.), a lecturer at Addis Abeba University (AAU). He argued that universities unable to meet the new standards should either change their line of business or suspend specific programs until they can comply.

“If they can't employ PhD-holding instructors, they should stop offering those courses until they can meet the requirements,” he said.

According to education officials, the new directive will soon be applied to public universities, pursuing to improve quality, increase accountability, and set a higher standard for all institutions.

Education experts have largely supported the move. Alemayehu blamed many private colleges for having contributed to declining standards and described the officials' actions as overdue.

“The Authority should have taken this decision earlier," he said.

Alemayehu believes that public universities in peripheral regions have outperformed many private institutions in Addis Abeba on national exit exams. He urged parents to be cautious when selecting colleges, warning that school closures often leave students stranded.

“If a school is forced to shut down, students are left in a difficult situation," he said. "However, it is still better for them to attend classes in a qualified institution rather than continue in one that is unfit.”

One such affected student is Sitra Nasser, a third-year accounting student enrolled at a private university. She was shocked to hear that her college might be closed. She already went through one closure, when Harambe University shut down, forcing her to transfer and scramble to get her documents in order.

“It was so difficult to get my documents on time," she told Fortune. "Without them, I couldn’t even get a student ID card at my new school."

Sitra pleaded for the ETA to consider the plight of students like her.

“Students are the ones who pay the real price,” she said. “It’s frustrating and costly.”

PUBLISHED ON

[ VOL

, NO

]

Commentaries | Jan 26,2019

Agenda | Aug 14,2022

Radar | Dec 15,2024

Fortune News | Aug 17,2025

Sunday with Eden | Aug 25,2024

Fortune News | Apr 28,2024

Radar | Aug 31,2019

Radar | Sep 21,2019

Fortune News | Aug 30,2025

Fortune News | Jul 19,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...