Commentaries | Dec 11,2020

Oct 20 , 2024

By Bjorn Lomborg

Children's educational test scores are a major cause of concern worldwide. Learning plummeted nearly everywhere during the COVID-19 pandemic, and standardised test results for mathematics, science, and reading were heading in the wrong direction even before that.

Education unites parents worldwide, although the level of challenge differs. American and rich world results stagnate at relatively high levels, whereas children in the world's poorer half struggle with even reading a simple sentence or doing basic math. However, after years of experience, it has become clear which policies do not work, even if they have loud backers. Increasing spending for a pupil sounds like a no-brainer, but it can deliver little or no learning if the money is not used wisely.

India showed this when it increased spending per primary school pupil by 71pc over seven years, but reading and math test scores still declined sharply.

The go-to policy for many teacher unions and politicians is making classes smaller. This sounds like it should make a big difference. Teachers can devote more time to individual needs, but analysis finds that reducing class sizes is one of the least cost-effective ways to improve student learning. A 2018 review of 148 reports from 41 countries found smaller classes had "at best a small" effect on reading proficiency and no effect on math.

Another favoured approach is paying teachers more. But even dramatically increasing salaries can have little effect on learning.

Indonesia embraced all these popular policies at once. It doubled education spending to achieve one of the lowest class sizes in the world while doubling teachers' pay. Yet, a landmark randomised controlled study showed "no improvement in student learning."

The awkward truth is that the commonly promoted approaches — increasing teacher salaries, lowering class sizes, and building more schools — are costly and do little or nothing to improve learning. There is, however, a promising policy that comes from an unexpected place.

Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the world, has suffered from overcrowded classrooms, a lack of learning materials, and a shortage of trained teachers. It is not somewhere we might expect to find innovative solutions. Yet it is now embracing an educational policy that shows hope in turning things around, and is even being scaled and adapted elsewhere. When the Copenhagen Consensus Centre [Disclaimer: The author is a founder of the Centre.] and the Malawian National Planning Commission joined forces to identify the most powerful, cost-effective policies to boost Malawi's well-being and growth, one educational policy emerged above all others.

Technology-assisted learning sounds deceptively basic. But it solves an often intractable problem. Almost universally, schools put all nine-year-olds in one grade, 10-year-olds in another, and so on. But, many of the children in each class are either far behind or far ahead. Kids in Malawi now use personalised, adaptive software on a tablet for one hour daily. It first identifies where each child is, then teaches it reading, writing and numeracy at his or her exact level.

Teachers describe how amazed they were to start using the software, and discover that their entire classroom of kids would become fully engaged. Children have described the relief of not worrying about being embarrassed about getting a wrong answer in front of their peers, or being forced to compete for time with the teacher. The policy is incredibly cheap, costing as little as 15 dollars for a pupil annually in Malawi, partly because using the tablet one hour a day means it can be shared among many students.

Extensive studies show that spending one hour each day on a tablet can deliver an astonishing three years of regular learning. Improved learning eventually translates into more skilled adults who will be more productive in the workforce and command a higher wage. Using standard economic estimates, this would mean that one year of children spending one hour a day on a tablet will command a lifetime income increase of roughly 16,000 dollars.

Given that most of this income would arrive decades into the future, the present-day value of that benefit could reach 1,575 dollars. That is a phenomenal 106-fold return on a 15-dollar investment.

Malawi is in the process of scaling up the policy to all its 6,000 primary schools, and encouragingly, costs are proving to be even lower, making the policy even better. Almost 300,000 children work at a tablet one hour a day, intending to reach all 3.8 million children in grades one to four by the end of this decade.

Malawi's determination shows how the entire poorer half of the world could improve learning for nearly half a billion primary school children. Sierra Leone and Tanzania are already working on implementing the same approach.

Our analysis shows that across the poorer half of the world, an educational investment of 10 billion dollars in delivering this approach would deliver more than 600 billion dollars in benefits annually, boosting future productivity. This approach could also be helpful in rich countries, with early evidence from trials in the United Kingdom (UK) looking promising. Parents worldwide are desperate for policies and approaches that could turn around poor test scores and ensure that kids are better equipped for the challenges of tomorrow. Tablets to teach at each student's level offer a powerful way forward.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 20,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1277]

Commentaries | Dec 11,2020

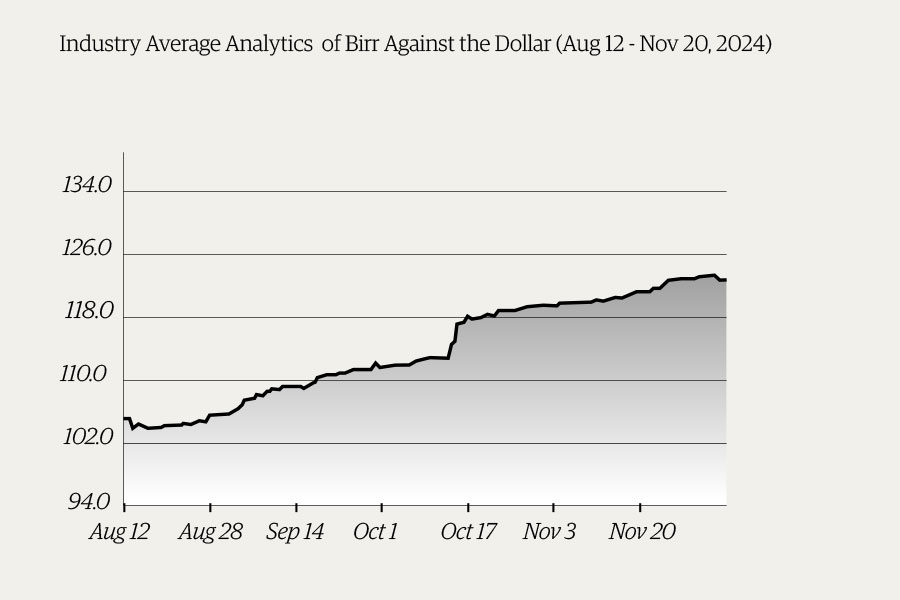

Money Market Watch | Dec 08,2024

Featured | Sep 08,2019

Fortune News | Jun 23,2019

Viewpoints | Aug 23,2025

Fortune News | Nov 16,2019

Commentaries | Jul 31,2021

My Opinion | Sep 10,2023

Editorial | Jan 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155081 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 145354 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 135156 Views | Aug 14,2021

Photo Gallery | 133829 Views | Oct 06,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

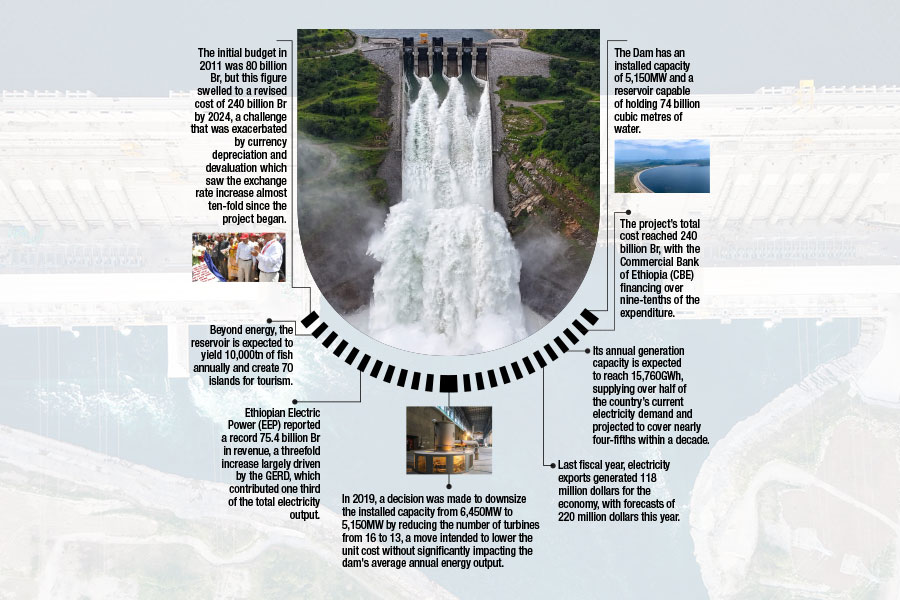

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric power proj...

Sep 13 , 2025

The initial budget in 2011 was 80 billion Br, but this figure swelled to a revised cost of 240 billion Br by 2024, a challenge that was exac...

Sep 13 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Banks are facing growing pressure to make sustainability central to their operations as regulators and in...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Cabinet has enacted a landmark reform to its long-contentious setback regulations, a...