Fortune News | Jan 22,2022

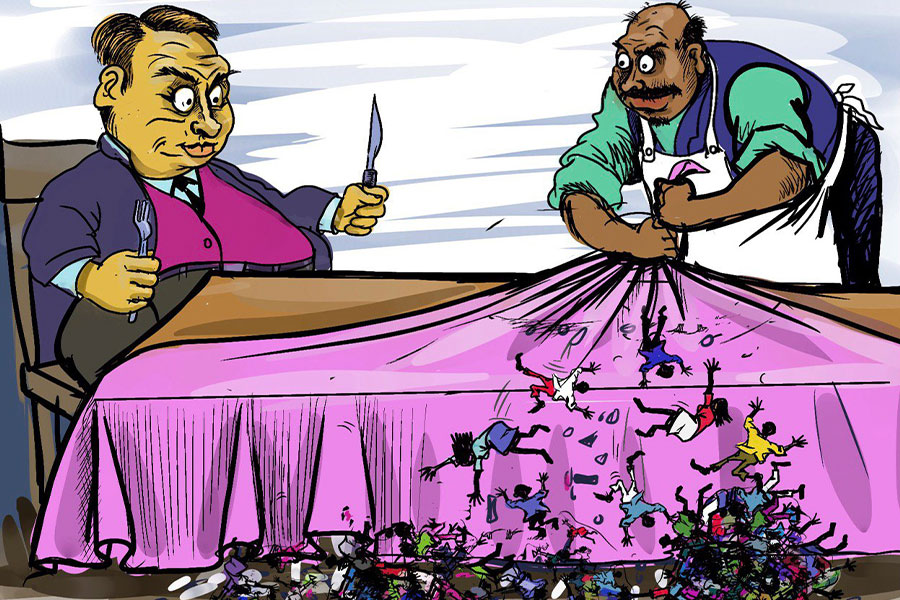

The past two years have seen more than their fair share of tribulation. A global pandemic, desert locust invasions, economic stagnation, political instability, runaway inflation and a full-blown civil war are only a few of the talking points on the list of calamities plaguing Ethiopia.

The issues have been the centre of conversation in Addis Abeba. But for Abdul Farah, 73, a resident of Gode Wereda in the Somali Regional State's Shabelle Zone, they are passing thoughts. He and his 13 children are caught in a much more pressing problem. With the public's eye fixated on the militarised conflict that has been raging in the country's north for almost a year and a half, a catastrophic drought in the east and south has gone largely overlooked.

Seasonal rains between October and December have failed. The unprecedented three-season drought sequence is taking a heavy toll in the Somali and Oromia regional states. Several areas have seen almost no rainfall for two years. Livestock, essential to the largely pastoral areas affected, are dying each day. But at the heart of the draught are close to four million people like Abdul.

Two years ago, Abdul had a herd of more than 60 goats, cattle and camels. The animals were a lifeline for Abdul and his family, who depend on them for nutrition and income. However, three consecutive seasons without rainfall have wasted the herd. Only nine survive today. Even the survivors are not healthy enough to sell.

"Not even to eat," said Abdul.

Before the drought, one of his cows would have fetched 27,000 Br in local markets. Abdul cannot get a buyer for 1,800 Br now. The plight has made him send six of his children to stay with relatives in Jigjiga, a seat of the regional administration.

Shabelle Zone is one of nine severely affected in the Somali Regional State, putting the lives of 3.2 million people at risk. Half a dozen zones, including East and West Hararghe, in the neighbouring Oromia Regional State, suffer from drought, endangering over half a million lives. Conditions in these areas are worsening by the day as food and water become more scarce. Children have had to drop out of school while many choose to leave.

"For the first time in 4 decades, Ethiopia is experiencing a prolonged drought with three poor rainy seasons in a row," reads a tweet from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA).

Most of the population in the vast semi-desert plains of eastern and southern Ethiopia are pastoralists, raising livestock on land otherwise unsuitable for agriculture. Like its arid neighbours in the Horn of Africa, the eastern part of Ethiopia has become measurably drier and increasingly hotter. Over the past two decades, four severe droughts have wreaked havoc in the area, a rapid succession of calamities that has pushed millions to the edge of survival.

The drought cycles are becoming more frequent in the Horn of Africa due to temperature changes in the Indian Ocean, says Eyasu Mekonnen, who pursues a doctoral study in climate-smart agriculture and biodiversity conservation at Haramaya University.

“Drought is a vicious cycle, and people are going from one crisis to another with very little breathing room to take stock,” he said.

The Shebelle, the main river in the central Somali Regional State, is having its water volume reduced. Untold numbers of pastoralist households like Abdul's used to flock to the river banks to fetch water for their homes and livestock. Some would trek on foot for hours to find water on the Shebelle River. Eventually, it got so bad that fetching water from the river was close to impossible without the help of water pumps.

The drought has killed over 1.4 million heads of livestock in the Somali Regional State alone.

Many are unable to afford to buy pumps.

“We live on the edge,” said Abdul.

The lack of water has been disastrous for the pastoralists' most valuable asset: livestock. Herders report losses of more than 70pc of their animals, and the death toll has surpassed 1.4 million heads of livestock in the Somali Regional State, disclosed Abdulfatah Mohammed, deputy head of the regional state's bureau for disaster prevention and preparedness.

“The carcasses of dead animals are piled up in the streets,” Abdul told Fortune.

Nearly three-quarters of the livestock in Abdul’s village have died. In Shabelle Zone, drought has killed at least 45,000 cattle, goats and camels.

Neither have government response efforts been very encouraging. Adem Ahmed, the administrator of Shabelle Zone, says 17 trucks have been assigned to distribute water to the residents of his jurisdiction.

However, the emergency humanitarian provisions are but a drop in the bucket. Eyasu, who has also taught at the School of Natural Resources Management & Environmental Science at Haramaya University for the last 13 years, argues that a better understanding of what the future may hold will help people living in arid areas cope with the consequences of climate change.

“Enhancing irrigation schemes and diversifying rural livelihoods through social protection and introducing cash-transfer programmes can be useful tools," he said.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) echoed similar thoughts during his visit to Jigjiga last week.

“We'll scale up the provision of water trucks, food, animal feed and essential medicines," he said during the visit. "We will accelerate the small dam projects we've embarked upon to support water management in lowland areas as a pathway to circumventing future droughts.”

It is a message that comes too late for Ibrahim Alefe, a resident of Shekosh Wereda in Korahe Zone, one of the worst affected in the Somali Regional State. He and his family, with 12 children, had a herd of 90 well-fed and watered goats a little over a year ago. Only six of them have survived.

Ibrahim says the worst loss has been that of his camels. He once owned a herd of 65, more than enough to sustain his family. Nearly all of them have died over the past year. The toll on these drought enduring mammals illustrates how dire the situation has been. Close to 27,000 heads of livestock have died in Korahe alone.

“It’s unheard of,” says Ibrahim, “I have never known them to die like this.”

Close to 400,000 people in 10 weredas of Korahe need emergency relief assistance. However, only three are receiving aid, according to Abdulnasir Hassen, early warning and response coordinator for the Zone.

“The assistance we're receiving is insufficient," he told Fortune. "We're prioritising the most affected areas.”

The lack of aid and the decimation of herds forced Ibrahim, his children and two wives to leave Korahe a month ago in search of food and water. They are among 4,000 displaced from the area and 220,000 in the regional state. Ibrahim and his family are taking refuge in one of the 35 temporary shelters to house internally displaced persons (IDPs).

“We're only receiving enough to sustain our lives here,” he said. "I'm hoping for a miracle at this stage."

The situation in Southeastern Oromia Regional State is no different.

Mechi Korecha, 26, a father of one, lives in Arero Wereda of the Borena Zone. His herd of 100 sheep and goats has dwindled to 15 over the past couple of years. Nothing can grow on the 2.5ht of land he farms. However, his chief concern is the safety and health of his child, who is already malnourished.

“All I can think about is my child’s future,” he told Fortune.

Malnutrition cases are doubling in Oromia Regional State. Incidents of diarrheal cases among children under the age of five are increasing, according to a report from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Authorities at the regional and federal levels are struggling to cope with the scale of the emergency.

The Somali Regional State cabinet has approved 200 million Br to pay for emergency relief. Its counterpart in the Oromia Regional State has stamped half a billion Birr for the response efforts. These are funds nowhere near enough to overcome the drought's grim impact on the population.

“It's impossible to assist all affected people,” said Adem, the head administrator of Shabelle Zone.

The federal government has supplied close to 5,000 quintals of rice and nutritious food items to the Somali Regional State.

International aid organisations are on the scene, but they too are struggling to cope with the sheer size of the disaster. The World Food Programme (WFP), whose director for Africa had visited Jigjiga two weeks ago, has supplied 1.1 million quintals of food aid. The federal government has appealed to the organisation to provide an additional million quintals of rice and nutritious food to the Somali Regional State, according to persons close to the matter.

There are mounting fears that even higher numbers of people will be exposed to the drought as the next dry season approaches.

“If the drought continues like this, livestock populations will plummet to almost zero,” Abdul fears.

Beyond anxiety, the management of droughts needs a paradigm shift, says Eyasu, the climate expert.

“Governments of poor countries should recognise the traditional approach of mitigating drought is no longer viable," he said.

Eyasu urges officials consider resettlement programmes in response.

"The relocation of herds and the use of special reserved areas can be useful strategies,” he said.

Pastoralists like Abdul and Ibrahim have little choice but to hope for rain or outside help in the meantime. Nonetheless, help is not coming in time or in sufficient amounts.

Humanitarian organisations face deep budget constraints for their operations in Ethiopia, while the number of people in need of emergency assistance grows to record highs. A UN report published last month estimated 22 million Ethiopians would require emergency humanitarian assistance worth 1.4 billion dollars this year. Close to 900 million dollars in funding has yet to be raised.

Urgent action is needed to reverse deepening drought impacts in southern and eastern Ethiopia, reads the report. Although the report authors chose to describe the alarming situation as a "continuous drought-like condition," they see what is unfolding in southern Oromia and Somali regions with "particular concern.”

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 29,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1135]

Fortune News | Jan 22,2022

Radar | Dec 02,2023

Fortune News | Sep 30,2021

Editorial | May 31,2025

Radar | Feb 19,2022

Fortune News | May 23,2021

Radar | May 25,2019

Radar | Apr 09,2022

Fortune News | Feb 18,2023

Radar | Dec 10,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...