View From Arada | May 29,2021

The hectic, narrow streets of Mercato seemed busier last week than the usual. A wave of last-minute shoppers looking to buy supplies for the Timket (Epiphany) holiday festivities may have caused the surge in traffic. Mercato was awash with noise and a flurry of activities around noon on a workday. Thousands of traders had their best goods on display, hoping to attract customers visiting an open market often touted as the largest on the continent. The market and its numerous quarters cater to every need, from clothing and electronics to foodstuffs and agricultural inputs.

Among the flood of shoppers fluttering about on that hot, sunny afternoon was Wendimhun Ginchil. A father of two, he was rushing between stores in Somali Terra, the market section with many traders dealing in spare parts for vehicles. This part of Mercato is also notorious as a graveyard for stolen cars.

Nonetheless, it has long been the destination for drivers, vehicle owners and mechanics in the capital searching for hard-to-find spare parts. Wendimhun was in the neighbourhood searching for a water pump for his Russian-made LADA model. He makes a living driving a blue-and-white taxi, barely hanging on to a trade pushed to the edge by the rapid rise of ride-hailing services. His income has been waning; to make matters worse, his car broke down a couple of weeks ago, leaving him idle.

"I'm barely making enough to support my family," he told Fortune.

The breadwinner in his family, Wendimhun had to visit Somali Terra to replace his faulty water pump. The model he drives is so old that parts are not found in markets elsewhere in the city. He had visited Somali Terra in the days prior but left without buying what he had come for upon hearing the prices quoted by dealers. Unable to find the water pump anywhere else, he had to return.

“People told me the only place I can find spare parts taken from other old cars is here,” he said.

Wendimhun found what he was looking for. To his surprise, the water pump price had jumped an extra 100 Br since his first visit a week earlier. However, he was in a tight bind and agreed to pay 3,600 Br to get his car back on the streets.

"My car is my only source of income," he said.

For tens of thousands of drivers in the transport industry, fuel expenses, servicing, and the cost of spare parts for aged vehicles become unbearable. Not only are prices on the steady rise, but the parts themselves are difficult to find even on dealers' shelves in Somali Terra.

The conundrum is the result of a cocktail of factors. The COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, global logistics disruptions, foreign currency shortages and tax policies are all culprits behind the unprecedented cost to keep vehicles running. Vehicle owners have little choice but to shell out exorbitant amounts of money for spare parts indispensable.

Melaku Moges, who runs a tour and travel business, has an illustrative story. Two months ago, he went shopping for spark plugs (also known as candela) in Teklehaimanot, another area not far from Somali Terra that serves as a hub for spare-parts trading. He bought a pack for a little over 1,000 Br. Melaku returned last week looking for more spark plugs for another vehicle; he was told it would cost him an additional 350 Br.

“The price is outrageous,” Melaku told Fortune. “But I have no choice."

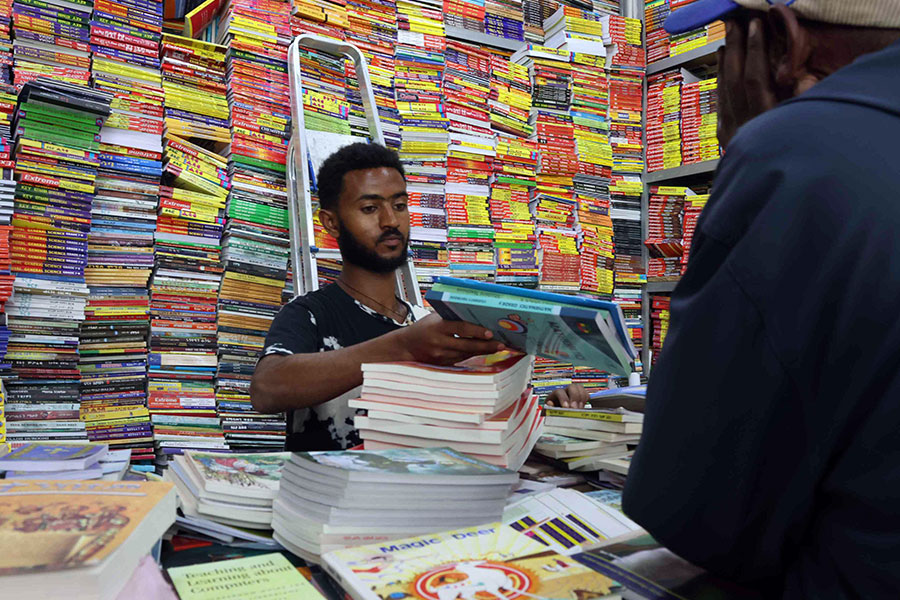

As is evident in the picture above, Toyota remains the leading vehicle brand in the country. A factor behind the popularity of the Japanese car maker is the readily availabile spare parts. Over the past few months, however, even Toyota drivers have been struggling to find the parts they need.

Walelegn Tolcha, the owner of the spare parts shop where Melaku bought the plugs, had few comforting words for his customer.

“You can go to any shop in the city and check for yourself; this is the current market price,” he said.

On the same day that Melaku searched for spark plugs in Teklehaimanot, a crowd was queued up inside the compound of one of the Motor & Engineering Company of Ethiopia (MOENCO) branches, an exclusive dealer of Toyota vehicles in Ethiopia. Close to 40 vehicle owners were lined up to buy spare parts at the sales centre at its headquarters near Hayat Hospital in Bole District. The sales staff operating eight windows had little time for a break as customers poured in one after the other.

MOENCO, a subsidiary of Inchcape, a London-based company in the automotive industry, sells Toyota vehicles and provides spare parts. Founded in 1959 with an initial capital of 200,000 Br, MOENCO took over the Toyota franchise business in Ethiopia in 1968.

Haji Abdurahman was among those in line that day, buying a side-view mirror for his Toyota Vitz model. A little over a year ago, he had bought an identical product from Somali Terra for around 1,500 Br. Dealers there have run out of stock, leading Haji to make his way to MOENCO. He ended up paying close to 9,000 Br for the mirror.

“I can’t believe I had to spend that much," he said.

Although the prices of spare parts may vary widely depending on the make, model and year of manufacture, the market has seen blanket increases. Three months ago, a name-brand oil filter (locally known as filtro) cost 350 Br. It has since jumped to 500 Br.

Brake pads of the well-known Asmico brand have seen prices triple to 1,800 Br over the same period, while prices for a high-quality water pump sit near 5,000 Br, up from 3,500 Br. Such a dramatic jump in prices within a short period has come as a shock even to Walelegn, who has been in the spare parts business for the last two decades. He is familiar with the ups and downs of the spare parts market.

“But I've never seen prices shooting up like this,” he said.

Ethiopia imported 13 major automotive spare parts, including brakes, gearboxes, suspension systems and radiators last year. According to data obtained from Customs Commission, it cost the economy close to 13 billion Br in 2021, showing a 12pc growth from the previous year. Much of it, accounting for 33pc of the total value, comes from China. Its neighbour, Japan, follows with a little more than three billion Birr's worth of spare part imports.

In economic parlance, it is known as a balance of payments deficit – the gap between what a country receives in foreign currency and its spending to pay for its imports. Ethiopia's woes in forex crunch have been looming for years. What it offers to the world in goods and services can only cover one-fourth of the 16 billion dollars in import bills, an average over the past five years. Revenues from the exports of goods stood at less than three billion dollars during this period.

Walelegn blames the unavailability of foreign currency for the escalating prices.

Fewer spare parts are making their way into the country, and prices are ascending as a result. Although the figures from the Customs Commission show growth in costs for imported spare parts, they also reveal the volume declined by 11.6pc to nearly 19,000tn last year. The dip in import volumes for spare parts contrasts with the growth in the number of vehicles on the country's roads. The figure had hit 1.3 million by the end of the last year, double what it was in 2014.

The empty shelves in Walelegn's shop are a testament to this.

Located on Tessema Aba Kemaw St., near Teklehaimanot roundabout, his store is no larger than 16sqm. It is a medium-sized store by the neighbourhood standard. Inside, the shelves on both sides of the store were almost empty. Only a few spark plugs packed in small corrugated boxes were scattered around. Half the shelf behind him was filled with original packed brake pads. On the floor near the door, five oil filters lay around.

“I stopped importing a year and a half ago because no forex is available," he told Fortune.

Walelgn blames long waits with the processing of obtaining letters of credit (LC) from commercial banks as part of the reason why he no longer makes an effort to import spare parts. The same issue faces bigger players in the market like MOENCO.

Yonas Wolde, after-sales director at MOENCO, says the long wait time causes the company to face shortfalls in its spare parts stock.

"We're forced to open LCs with up to four banks to get the required forex," he told Fortune.

Fuel pumps, brake pads and oil filters are the parts with the most demand at MOENCO.

The spare parts business is hardly alone in having difficulties accessing forex. Regulators at the central bank have issued directives rationing the meagre forex available among items designated as 'essential' before responding to the demands of importers like Walelegn. They are in the tail of the line.

The disabling forex shortage is pushing spare parts importers out of business. Close to 46 licensed imports were dropped last year from the 292 a year before.

The shortage forces others to look for alternative sources of foreign currency.

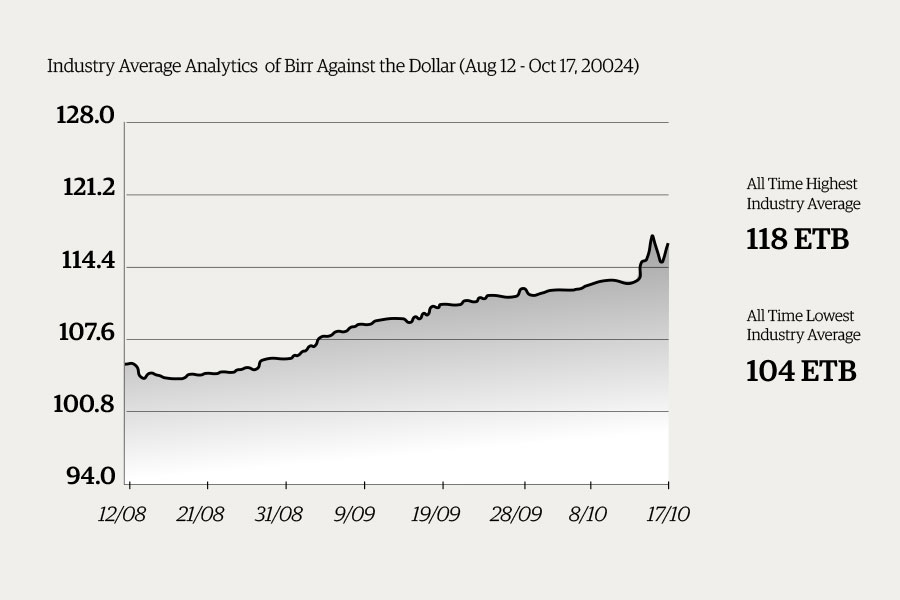

Desalegn Tesfaye, an importer and owner of Desu Spare Parts store in the Qera area, appears to be determined to stay on for now. However, his decision has come at a high cost. He mainly imports suspension systems for Toyota Vitz models. The latest shipment he ordered, two containers, arrived two weeks ago but cost 30pc higher than what he would have paid previously. The exchange rate of Birr against the Dollar, which hovered around 44 Br last July, surpassed the 50 Br mark in the final days of 2021.

This has pushed the import bill even higher.

Ethiopia spent around 612,000 Br to import a tonne of spare parts two years ago, a value increased by 62,000 Br the following year.

A global shipping crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic is also part of the problem. As lockdowns and restrictions began to take hold across the world in early 2020, factories in China, which produced nearly a third of all manufactured goods and recorded exports of almost three trillion dollars, shut down. The impacts were immediate.

E-commerce saw a boom as more people stayed home doing their shopping, bringing with it great demands for logistics and shipping services. When Chinese factories resumed operations, they had a backlog of orders to meet. Shipping giants like the Denmark-based Maersk began charging more than five times the pre-pandemic fees to ship containers to the United States or Europe from China. The price of shipping a single container to these markets surpassed 20,000 dollars, up from 4,000 dollars two years ago.

Businesses in Ethiopia were not insulated from this global choke on the logistics industry.

The state-owned Ethiopian Shipping & Logistics Services Enterprise (ESLSE) quadrupled its freight tariffs last May, attributing its decision to running short of shipping containers. Shipping a 40ft container from ports in China to Djibouti costs an importer around 10,000 dollars.

The abrupt rise in prices has played a part in the falling volume of spare part imports. But policy frameworks such as the newly-revised import duty tariffs have also had an impact. Last August, the federal government revised customs duties for close to 6,000 imported products, including a five-percentage point increase to the 25pc imposed on vehicle spare parts.

The revision is intended to encourage domestic industries, according to officials at the Commission.

The authorities slashed import tariffs for domestic companies that assemble vehicles, mobile phones and television sets. Raw materials importers for local manufacturing also received duty cuts. Although the government expects the revision to usher in a significant change in the manufacturing industry, its effects have been detrimental to the vehicle spare parts market.

Desalegn is among the businesspeople who finds himself on the receiving end of the tariff increase. But he learned about the changes after he had ordered the parts from China.

When the sudden and rapid rise of costs will stabilise remains unclear. For now, cab drivers like Wendimhun have their hands tied.

“I can’t afford to be out of work anymore," he said. "My family depends on it."

Ironically, the amount he paid for the water pump in Somali Terra last week consumes more than two weeks of his income. The family would see less of what the LADA taxi used to bring home.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 22,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1134]

View From Arada | May 29,2021

Radar | Aug 23,2025

Fortune News | Jul 17,2022

Fortune News | Jun 29,2025

Advertorials | Jan 02,2020

Viewpoints | Jan 05,2019

Money Market Watch | Oct 20,2024

Radar | Sep 04,2021

Sunday with Eden | Apr 22,2023

Agenda | Oct 05,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...