Radar | Nov 04,2023

Aug 14 , 2021

By Christian Tesfaye

It has been an interesting week for the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). It sent out a message to all commercial banks that is consequential, to say the least. It ordered all collateral-based bank loans, even those loans that have been approved before it sent out the message on August 11, 2021, to be frozen.

How long it will last and why it did as such is not entirely clear, but “economic sabotage” has been suggested. It may well have to do with the sudden uptick of the black market value of the dollar, which has been selling for up to 70 Br, from just below 60 Br a few weeks ago. Banks are currently selling the dollar for under 46 Br. While there has always been a marked difference between exchange rates over the two markets – which is natural in economies without a flexible exchange rate regime – this one is different.

It is entirely possible that it is a consequence of an attempt to fly out a large amount of capital from the country. Although it could have significant impacts upon the economy if loans are frozen for too long, the central bank's decision is understandable if they are attempting to fight a sudden rush of capital flight.

The episode offers an interesting case study of what would happen if Ethiopia removed capital controls and floated the currency. The black market serves as a flexible exchange rate regime without central control. The market sets the prices. Thus, when there is a sudden spike in demand for dollars, the value of the Birr falls as many people cash out. Floating the Birr amounts to this but in the official market without the cost of operating informally added. Removing capital controls will precipitate this even more.

What makes a flexible exchange rate market dangerous is speculation. Asian countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines learned this the hard way in the late 1990s when governments' inability to support their currencies led to massive capital flight. Speculators noticed and began shorting currencies such as the Thai Baht. A simple way to do this would have been to take out loans from local banks in the Baht, knowing that by the time it is paid back the currency would have likely been floated and its value depreciated to the extent that the borrower would be making a profit even when interest rates are figured into the equation.

A country that managed the crisis well was China. Capital controls were effective as foreign investment was mostly on tangible goods. A non-flexible exchange market allowed the Chinese government to maintain the peg without much speculation in the economy.

This contrast between the likes of Thailand and China is not the end of the debate on whether or not to open up the economy, especially its financial markets. But it provides a clue on what policies best suit a country in the face of uncertainty and speculative investments and trading.

More importantly, it is about the proactiveness of the central bank. Decisions made under such circumstances are highly complex. It is almost the case that it is near impossible to choose correctly. For instance, increasing interest rates is usually a popular monetary policy for arresting inflation. But it could also harm the economy by discouraging borrowing, which reduces investments and bogs down economic activity.

Analysing and feeling out the economy is necessary and proactiveness crucial. An assertive central bank takes charge when investors and savers are uncertain and confused. It also knows when to let go, when it sees productive potential that can be unleashed when markets are freed up.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 14,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1111]

Radar | Nov 04,2023

Sunday with Eden | Sep 28,2019

My Opinion | Feb 12,2022

Fortune News | Nov 25,2023

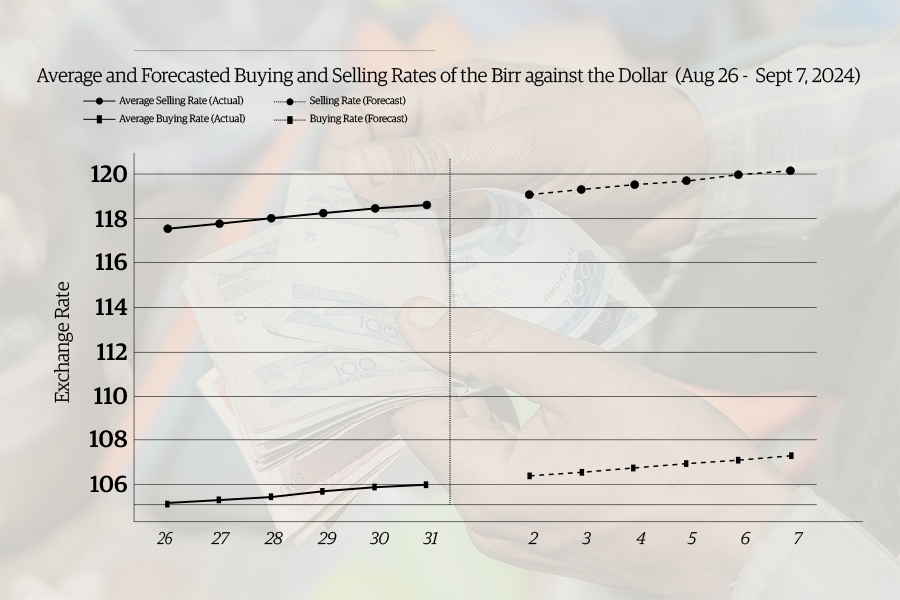

Money Market Watch | Sep 01,2024

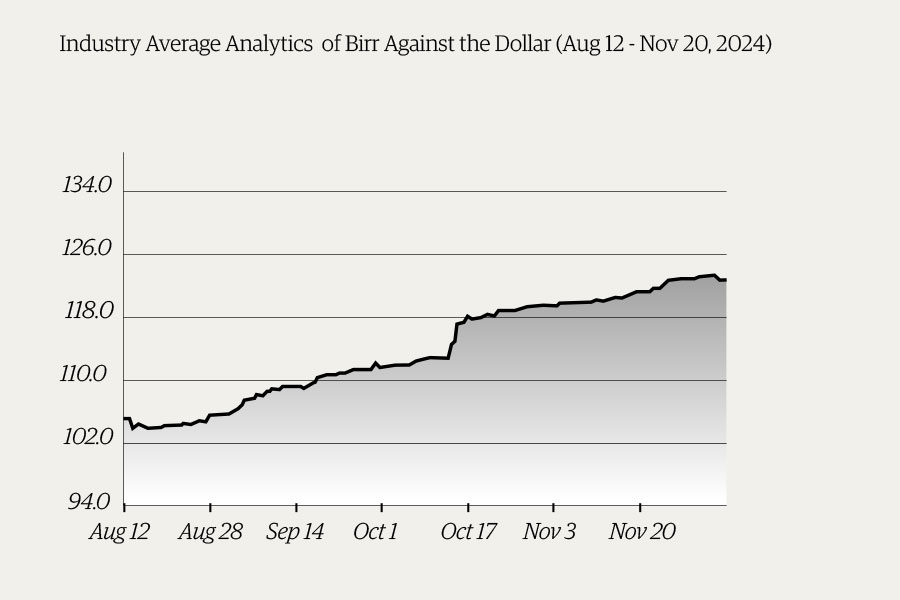

Money Market Watch | Dec 08,2024

Agenda | Oct 12,2019

Radar | Jun 30,2024

Radar | Jun 07,2020

Radar | Dec 02,2023

Photo Gallery | 172638 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 162866 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 152689 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136382 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In Meqelle, a name long associated with industrial grit and regional pride is undergo...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is set to roll out a new "motor vehicle circulation tax" in th...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The Bank of Abyssinia is wrestling with the loss of a prime plot of land once leased...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The Customs Commission has introduced new tariffs on a wide range of imported goods i...