Editorial | Sep 24,2022

Nov 29 , 2020

By Abu Girma Moges

Ethiopia has a legitimate right to make full use of its natural resources for the benefits of its population. Moreover, a richer and more prosperous Ethiopia is good for Egypt and the world, and the GERD is central to this endeavour, writes Abu Girma Moges (agmoges@gmail.com), associate professor of economics at the University of Tsukuba, Japan.

The advent of major climatic crisis across the vast Sahara region, about seven millennia ago, made the region inhospitable for humans and animals. The crisis triggered a phenomenon that made the Nile River the only lifeline on the eastern corner of the massive landmass. The river waters supported life, agricultural cultivation, fishing, transportation, trade, and eventually served as an anchor to Egyptian and Nubian civilisations.

While generations of Egyptians considered the Nile a gift from God and held that view in veneration, they could not trace the source of this generous river initially. As all things abstract, they cherished the blessings of nature to their gods and gave their offerings to favour them with the annual flows of riches from the upper streams. Despite the vulnerability of the economic foundation to the annual water flows of the Nile, this was a remarkable achievement of adaptation and resilience in the face of adversity.

But the Nile River was also transboundary water body and its basin extends across 11 central and northeast African countries. While repeated attempts and efforts to control the entire basin were unsuccessful, Egyptian rulers used all their leverage to secure uninterrupted and full control of the Nile waters. Protecting this exclusive right has been the most enduring theme of Egyptian politics.

While Egypt might have been successful thus far in pressuring and upholding their hegemonic power over the transboundary water resources, the status quo has become increasingly unsustainable. There is simply too much inequality and unfairness in the way the riches of the Nile waters are utilised among the riparian countries. The legitimate demands for economic development have necessitated the urgency of exploring all options and opportunities to pursue equitable use of water resources. While Egypt and Sudan have enjoyed the benefits of freshwater inflows, they were content to ignore the plights of the people in the upstream countries for development and a better standard of living.

The increasing demand for equitable utilisation of shared natural resources would pose immediate challenges of reform in Egypt and Sudan. While the resistance is understandable and expected, it is time to pursue a new framework for basin-wide development endeavours for inclusive and shared prosperity.

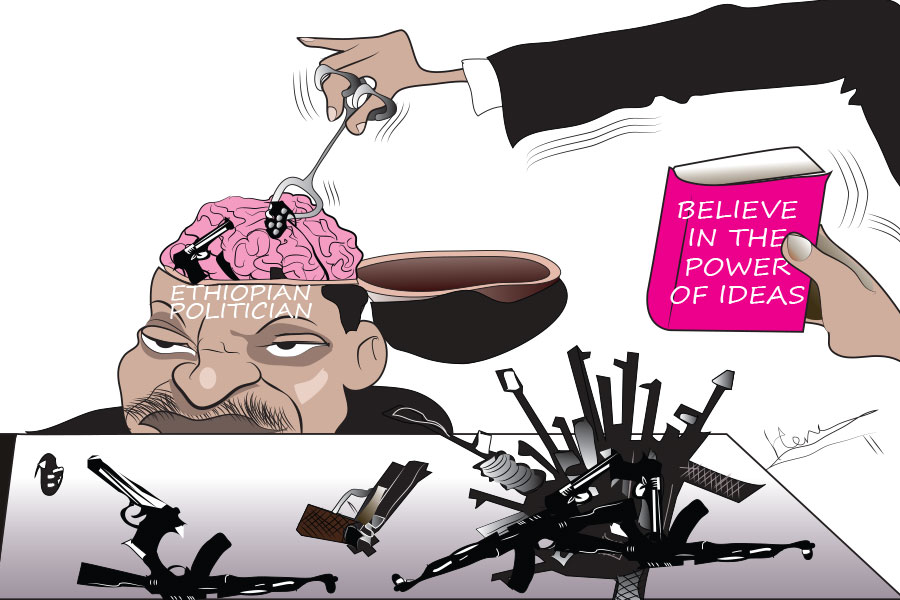

Making a case for this is the fact that the majority of the Ethiopians still live on subsistence agriculture and their life is excessively subject to the vagaries of nature. Despite its long history of civilisation and early initiation on the path to modernisation, Ethiopia remains economically underdeveloped, and its population is one of the poorest on earth. Moreover, misguided economic policies have resulted in long term stagnation and abuse of the natural and human resources of the country. This reality of abject poverty in a country that is blessed with relatively rich natural resource endowments is a brutal fact of life and a consequence of misguided political and economic policy choices.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is a vital infrastructural project with a primary objective to generate hydroelectric power. It has no significant adverse impact on the average annual water flow to downstream countries once the reservoir is filled. Apparently, what Ethiopia is currently attempting to build at the dawn of the 21st century is what Egypt successfully managed to accomplish a century ago in 1902 at Aswan!

While the intention to develop the Blue Nile basin has been actively pursued by generations of Ethiopians, due to lack of financing and quite sophisticated conspiracies against the planned project, it is only now that the country mustered the will to initiate the project by its financial initiative.

The GERD is quite a complicated and costly project relative to the capacity of the domestic economy to bear the necessary financial and technical resources to complete the Dam. The project has faced significant delays, cost overruns, and widespread embezzlement from the meagre funds Ethiopians contributed.

While such problems need timely and just remedial measures, the priority now has to be completing the project as soon as possible and integrating its electricity generation into the electrification effort both within Ethiopia and the regional economies. The GERD has considerable ripple effects and can initiate a sustained structural transformation of the economies in the riparian countries.

Ethiopia and Egypt have somewhat similar population size, and yet Egypt runs a GDP in excess of 250 billion dollars compared to the stunted size of the Ethiopian economy at a third of the scale.

The relative dependence of these economies on agriculture for output and employment is also starkly different. Agriculture, which employs about 24pc of the labour force, contributes about 11pc of Egypt’s total output. In Ethiopia, two-thirds of the total labour force is engaged in the agricultural sector and makes up over a third of GDP.

Extremely low labour productivity in agriculture leaves the Ethiopian economy literally trapped in subsistence with chronic food insecurity. These economic features provide unique contrasts and complementary opportunities for collaboration that could benefit both economies and beyond. The relative economic muscle provides Egypt, should it choose to use it wisely, the opportunity to create a conducive environment for promoting critical investment to the wider regional economies. The overall effect of such endeavours pays significant returns both in sustainable economic growth and economic integration within the region. This is the most promising path to pursue for all the partners within the Nile basin.

On its own merits, Ethiopia has a legitimate right to make full use of its natural resources for the benefit of its population. Moreover, a richer and more prosperous Ethiopia is good for Egypt and the world. Widespread destitution incubates only hopelessness, instability and conflict. Conflict, whatever form it takes, is destructive and hampers development efforts.

Egypt has a mightier economic and military power in the region. And yet it has even more positive power to play a constructive role in mobilising critical investment resources for Nile basin-wide development initiatives. What it can gain by cultivating development affinity is by far better and everlasting than what it hopes to accomplish with military force or violence.

Egypt has hard choices to make. First, it has to carefully reflect on the implications of initiating a conflict with Ethiopia and subsequently depriving itself completely of future opportunities to negotiation on the water resources of the Nile. Second, if Egypt indeed intends to promote the interest of its poor farmers, it should choose mutually beneficial negotiation with Ethiopia.

Egypt will never win an armed conflict with Ethiopia over the Nile River issue. Ethiopians are carefully watching the choices that Egyptians are making regarding the Blue Nile. Any hostile action on the GERD will surely trigger an avalanche of reaction with dire consequences. If the GERD is attacked in one way or another, Ethiopia has all legitimate rights and means to protect its vital national interest.

Should Egypt choose the way of violence, it is bound to pay a significant price. With its strategic location at the source of the mighty Blue Nile River, Ethiopia has natural and extremely powerful leverage. Ethiopia, if it chooses to, has what it takes to inflict significant and long-term damage to downstream countries.

Whatever the level of its economic and military handicap might be, it does not take much treasure and blood to inflict considerable damage against provocative violence. By their strategic geographical advantage, Ethiopians could at least make the fresh waters of the Nile unusable to regional bullies.

Ethiopians have always been patriotic and would defend their sovereignty at any cost. All the same, Ethiopia can win the war over the Nile waters without shooting a single bullet. Reason and justice should remain the guiding principle of settling the competing claims of the stakeholders in the region.

No doubt, the current generation of Egyptians would muster the wisdom of their ancestors and seek the ways of peace with their neighbours in Ethiopia. Recognising the legitimate aspirations of its fellow Africans and a modest token of solidarity would go a long way to create mutual trust and friendship among the peoples of the region who had a long history of peaceful coexistence.

Conflict jeopardises the very objective of securing the equitable and shared use of the waters of the Nile. It is prudent and more sustainable to shift the perspective from rivalry to collaborative engagement that optimises the contribution of the GERD to the regional demand for energy and creating ripple effects on the rest of the economic sectors.

Ethiopia should focus all its effort in completing the GERD and start in earnest to address the more pressing problems of chronic poverty, unemployment and bad governance. Provocations and threats against the dam may trigger popular demands for a strong reaction. Just as this may be, restraint is necessary and prudent. In that spirit, Ethiopia should continue its stance of magnanimity towards its neighbours and endeavour to explain its position clearly to the international community. There is still considerable scope for collective development and mutual progress in the Nile basin, and all opportunities should be used to realise such rich and deep potential.

Apparently, both the falcon and the lion have their unique natural and innate ways and characteristics that humans cherish and fear at the same time. Taming the natural urges of the falcon and the lion, though challenging and not politically instinctive, is critically important for the sake of peaceful coexistence and survival in such a challenged region of the world.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 29,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1074]

Editorial | Sep 24,2022

Commentaries | Jul 03,2021

Agenda | Dec 05,2018

Viewpoints | Aug 01,2020

Editorial | Sep 23,2023

Commentaries | Sep 11,2020

Featured | Jan 02,2021

Editorial | Jun 29,2019

Commentaries | Aug 16,2020

Viewpoints | Aug 13,2022

Photo Gallery | 157365 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 147652 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 136248 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 135306 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

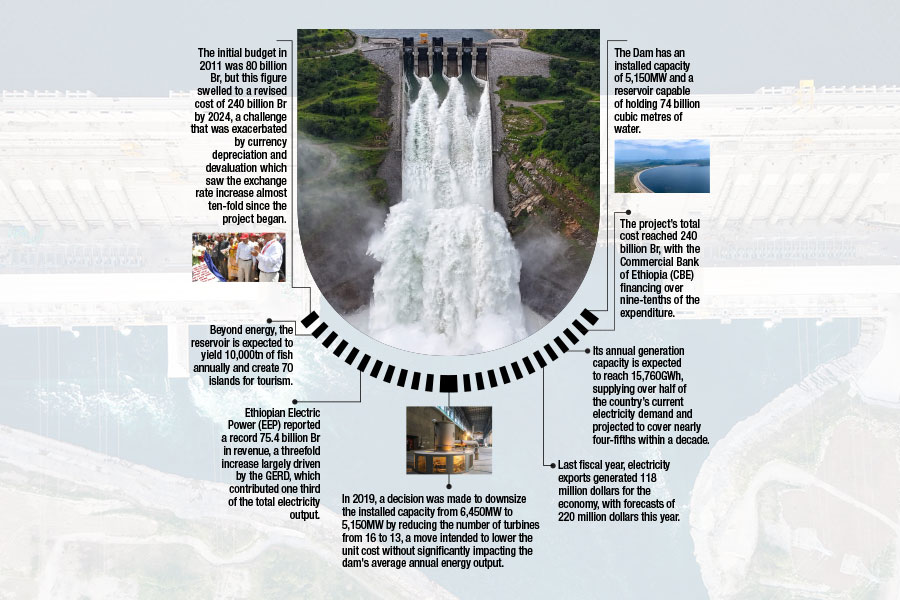

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric power proj...

Sep 13 , 2025

The initial budget in 2011 was 80 billion Br, but this figure swelled to a revised cost of 240 billion Br by 2024, a challenge that was exac...

Banks are facing growing pressure to make sustainability central to their operations as regulators and in...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Cabinet has enacted a landmark reform to its long-contentious setback regulations, a...