Radar | Dec 05,2018

May 23 , 2020

By Mesay Shemsu

Leiden, a city in the Netherlands, has managed to create streets that are first and foremost for the people as opposed to vehicles, something Addis Abeba has not managed to do for its residents. An important aspect in this regard is the separation of people from that of motorised traffic, which will, in turn, facilitate the design of good public spaces, writes Mesay Shemsu (reachmesay@gmail.com), lecturer at the Addis Abeba Institute of Technology and a professional civil engineer specialising in transportation.

Adear friend showed me around the streets of the city of Leiden in the Netherlands in March 2019. The city was very beautiful. The streets were alive. By day, people were out and about on the streets; one could see markets, street musicians and wide public spaces that host fine cafes. By night, vibrant activity from chic jazz bars and college fraternity and sorority houses spilt out onto the streets.

That night, as I sat in one of the bars, I had a nostalgic moment. My mind wandered thousands of miles away to Addis Abeba. It is my home – the one place on earth I would not trade for anywhere. I was then slightly upset that the streets of Addis were not like the streets of Leiden.

In Addis, there are wide roads on which cars swoosh past. Pedestrians are confined to narrow walkways. Oftentimes, these walkways are encroached upon by street vendors - themselves rightful contenders of the space - and outdoor cafes or extended enclosures related to construction activities.

I began contemplating what Leiden has that is missing in Addis to create a city that is first and foremost for the people as opposed to vehicles. An important aspect in this regard is the separation of movement of people from that of motorised traffic, made possible by well-designed public spaces. On Leiden’s streets, the pedestrian enjoys immense protection from motorised traffic on several fronts.

Primarily, the difference belongs to design and engineering. Because of longstanding cycling culture, the Dutch have developed an elaborate design guide to create pedestrian- and bike-friendly streets. Speed limits, speed bumps, sensor-based traffic lights and car-free streets are the armour that protect the Dutch cyclists and pedestrians. The low speeds of biking and walking, in turn, make for safe adjacent public spaces in ways motorised transport can never guarantee.

Then there is legislation. When a pedestrian or cyclist ventures onto the streets, they are small, fragile and vulnerable. Meanwhile, drivers are protected by their vehicles. In a city for people, legislation favours vulnerable people over motorised traffic by imposing many restrictions and penalties on motor vehicles. Such provisions are abundant in Dutch traffic law.

Just as important is the economics of the system. Enrique Peñalosa, the mayor of Bogota between 1998 and 2001, vividly described the fierce opposition he once faced in his bid to transform his city into a more people-friendly place.

Tough opposition came from shop owners who used to have their customers park on the side of the street. The shops feared they would lose business if these parking spots were sacrificed in favour of more public space. Instead, studies showed profits increased.

This mostly had to do with the fact that more customers walked to do their shopping than was estimated. The hassle of finding parking spots in the city centre was also quite a nuisance to shoppers. These reasons are indeed applicable to Leiden’s infamous shopping streets. On top of the health and environmental benefits of non-motorised transport, the above makes an excellent economic argument for a city like Leiden to favour non-motorised transport.

Finally, and perhaps more importantly, there is public movement and political will aiding a system that puts people before motorised vehicles.

If one studies how the Netherlands became friendly to non-motorised transport in the 20th century, it becomes apparent that traffic is, in fact, one of the most political issues in a city. In the aftermath of WWII, people saw more money in their pockets, giving them the ability to afford cars. Like the unethical commercials that advertise sugar-filled sodas to little children, the car was then advertised to the public as a chariot of speed and status.

The number of cars and car trips increased so much that by the 1970s the share of trips in Amsterdam made by bicycles declined to just above 20pc, a share four times smaller than was recorded in the 1950s. It was not long before people began to witness shocking statistics of car accidents, particularly on children. This gave rise to the Stop de Kindermoord - Stop the Child Murder, in English - movement against unsafe road infrastructure that favours the car.

Although some politicians took public appeals to heart, decisive action was not taken until a global oil crisis dealt the motor industry a huge blow, persuading Dutch politicians and policymakers to favour non-motorised transport in infrastructure design and investment. Now, Dutch streets are protected by politicians that acknowledge the benefits of cities fundamentally aimed at the people themselves, and a public aware of the need to organise and toil to realise cities that are primarily for the people.

In Addis, different studies estimate that private cars are used for five to 15pc of trips. As far as trip distances go, the average distance covered by a vehicle is 3.3Km, according to the latest data. This makes Addis a city that screams for street design that is friendly for non-motorised transport. Only a minority of the population uses cars and typically for distances that could be walked or cycled.

What, then, is Addis missing?

The experts needed to create a usable cycling network and equitable street spaces for the city are definitely here. So are the design experiences from other countries to learn from. And yet, dedicated infrastructure for cycling and adequate walkways are nowhere to be found. A number of reasons could be behind this.

First and foremost, this is explained by the inertia of the common way of doing things - roads are always designed for cars. A breakaway from tradition is required to set new trends in infrastructure design that benefit the majority. Some argue here that there is not enough walking and cycling culture in Addis to warrant alternative street designs.

But have we designed adequate, safe and comfortable streets for the cities of Bahir Dar, Meqelle or Awassa, where people cycle often and where our national bicycling champions most often hail from?

Another missing link is legislation. In this regard, walking is common in Addis and the legislation regarding pedestrians and their interactions with cars seems up to par. It favours the pedestrian when it comes to assigning blame for an accident. However, since bicycles and bike infrastructure are rare in Addis, legislation regarding the use and rules of biking is non-existent.

In general, the arguments for the positive environmental and health benefits of biking and walking are also no different in Addis. However, rigorous studies haven’t been made to show policymakers when and how they must invest in making the city spaces friendly for non-motorised transport.

If we want to precisely quantify the benefits of a certain investment we can use surveys to know how many people would shift to walking, cycling or both as a result of newly built bike routes and walkways. Then, the city will benefit from using fewer cars, suffering less congestion and pollution, enjoying previously wasted urban spaces, and experiencing fewer casualties due to poor road safety.

The Dutch case has shown that willingness and cooperation are necessary between the government and the public to achieve equity on the streets, that is, proper allocation of the available street space between different modes of transportation in a manner that is proportional to the total number of trips each mode is responsible for.

On this front, a lot remains to be done. People have yet to organise around the agenda for equitable city space. Most of the measures related to road use, safety and equity are coming from the top. It is indeed quite commendable that the Addis Abeba City Government is experimenting with what works for the city regarding non-motorised transport and implementing it.

But what happens when citizens do not own these initiatives as their own, or worse, when citizens do not even think of spatial equity as a personal right and responsibility?

Interestingly enough, people will not defend against the encroachment of cars onto designated walking, biking or even public transit spaces. The recently built bicycle paths around Lebu area and the pioneering trials of the bus rapid transit lines are good examples; there, unless traffic police spot them, drivers feel free to violate car-free spaces.

This shows that the people-friendly city is a co-emergent phenomenon that requires a conscious public and a responsible government - responsible not just for infrastructural investment but also for the awareness of the public regarding spatial equity. Indeed, I see the last front as the most important igniter of change in Addis Abeba. Citizens must, therefore, get on board and be brought on board in the fight for equitable streets - taking it on as a personal goal and a collective outcome.

PUBLISHED ON

May 23,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1047]

Radar | Dec 05,2018

Fortune News | Jul 26,2025

Agenda | Jun 15,2025

Radar | Aug 26,2023

Fortune News | Jul 13,2025

Fortune News | Nov 27,2022

Radar | Feb 02,2019

Agenda | Feb 09,2019

Radar | Jun 27,2020

Featured | Jan 05,2020

Photo Gallery | 150461 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 140728 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 134731 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 131303 Views | Aug 21,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

Aug 16 , 2025

A decade ago, a case in the United States (US) jolted Wall Street. An ambulance opera...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

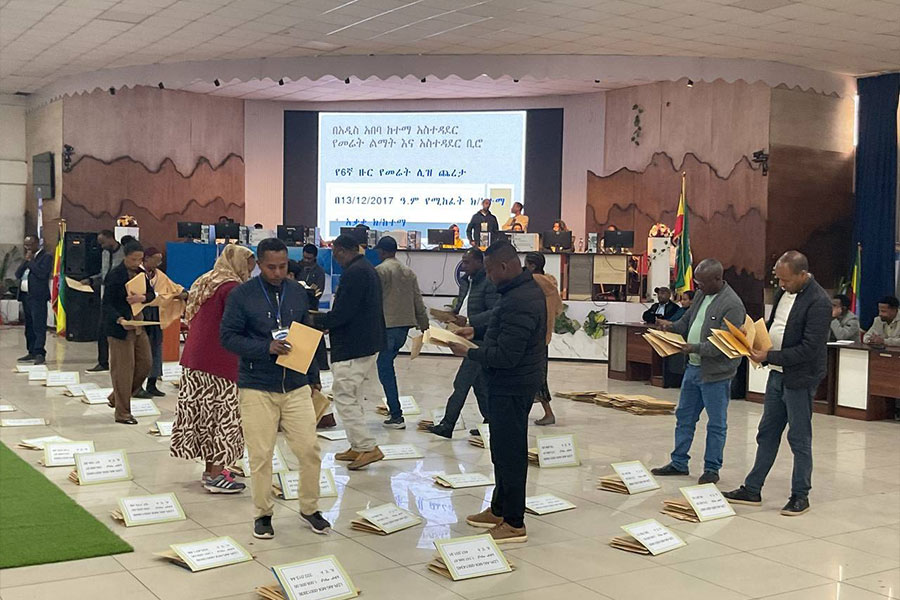

Addis Abeba's sixth public land lease auctions after a five-year pause delivered mixe...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Brook Taye (PhD), the chief executive of the Ethiopian Investment Holdings (EIH), is...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

For decades, Shemiz Tera in the Addis Ketema District of Atena tera has been a thrivi...

Sep 7 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A dream of affordable homeownership has dissolved into a courtroom showdown for hundr...