Radar | Sep 19,2020

Mar 28 , 2020

By Shimelis Araya ( Shimelis Araya is a doctoral candidate in economics at the University of Giessen, Germany. He can be reached at araya.gedam@gmail.com. )

Contrary to standard economic theory, behavioural economics outlines paradoxical “errors” we commit in our daily lives.

We have a psychological makeup that leads us to have a higher fear of something, without consideration of how deadly it is, as a result of public panic and media-driven outrage.

We are prone to biases that impact our decisions. Considering the global pandemic of fear that the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has unleashed, we could use a boost to our psychological resiliency based on the findings of behavioural economics.

Many studies have been conducted to understand the psychology behind how we make decisions. The research is fascinating and some of the authors of these studies have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in economics.

Among the ground-breaking books written in this field is Freakonomics, by Stephen Dubner, an award-winning journalist from the New York Times, and Steven Levitt, a young economist at the University of Chicago. It provides a unique way of understanding economics. With its provoking and stunning insights, it shows how we fail to make smart decisions in our daily lives and turns the conventional thinking on its head.

The authors started with uncommon research questions in economics - some concerned life and death situations, which could be utilised to reduce our anxiety about COVID-19.

One of their most interesting illustrations is the following example: Which is more dangerous, a gun or a swimming pool?

A family in the United States has an eight-year-old girl, Molly. She has two friends, Amy and Imani. Molly’s parents know that Amy’s parents own a gun. Hence, they urge their daughter not to go to Amy’s house, leading Molly to spend a great deal of time in Imani’s house, which has a swimming pool. With their “smart” choice, Molly’s parents feel that they are protecting their daughter.

But what they did, statistically speaking, was not smart. A child drowns for every 11,000 swimming pools in the United States. With six million pools, it has been concluded that around 550 children under 10 drown each year, according to the figures the book provides.

The statistics on the death of children with a gun, however, are very small. The probability of a child being killed with a gun is one for every million guns. With an estimated 200 million guns in the country, around 175 children under 10 die annually. Swimming pools are thus more deadly than guns. Molly is in far more danger at Imani’s than at Amy’s, statistically speaking. But most of us will probably make the same error as Molly’s parents did, guided by conventional wisdom.

Similar research has indicated that one in seven Americans is at risk of dying from heart-related illnesses, while death due to a terrorist attack is one in around 46,000 people. The probability of a person being killed in a terrorist attack is far smaller than the chance that they will die because of a heart attack.

Despite this, a new survey conducted in 2016 shows that people are deeply fearful of being killed by terrorists. Media exposure and government policy regarding terrorism increases public outrage despite the lopsided statistics.

Dubner and Levitt have provided an equation to gauge which risks can appear more dangerous to individuals. It is a combination of hazard and outrage.

“The thought of a child being shot in the chest with a gun is horrifying, thus, outrageous,” they state in their book.

However, a child drowning in a pool does not attract public outrage. “When the hazard is high, and outrage is low, people under-react,” and in turn there is less panic.

This is due to the familiarity effect. We are more familiar with swimming in a pool than we are with gunplay. This familiarity phenomenon was further explained by another concept called the mere-exposure effect, a psychological phenomenon where people prefer something simply because they are familiar with it.

It is for these reasons that we should not panic because of COVID-19. It started in China and has now spread to most countries. Everyone is in panic mode at a level that defies logical interpretation. The virus, which originated in China, can be treated, results in mostly mild cases, has a lower fatality rate compared to past outbreaks. There are even patients on the internet sharing how they experienced and recovered from the illness.

We should not be panicking when we consider the data. This, though, does not mean that precautions should not be taken.

We should follow the special hygiene and safety instructions and precautionary measures. Additionally, boosting our immune system through the intake of more Vitamin C-rich foods to fight off the virus is also recommended.

We should act responsibly to curb the transmission of the virus to others. Given the scarcity of resources, we should self-isolate once we show flu-like symptoms and contact the authorities. Social distancing has been shown to be an effective tool for fighting off the virus and keeping it away from those that are especially susceptible, especially elderly people.

With such precautions in place, the low fatality rate, most cases being mild and high numbers of recovery, there is no reason for complete doom and gloom.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 28,2020 [ VOL

20 , NO

1039]

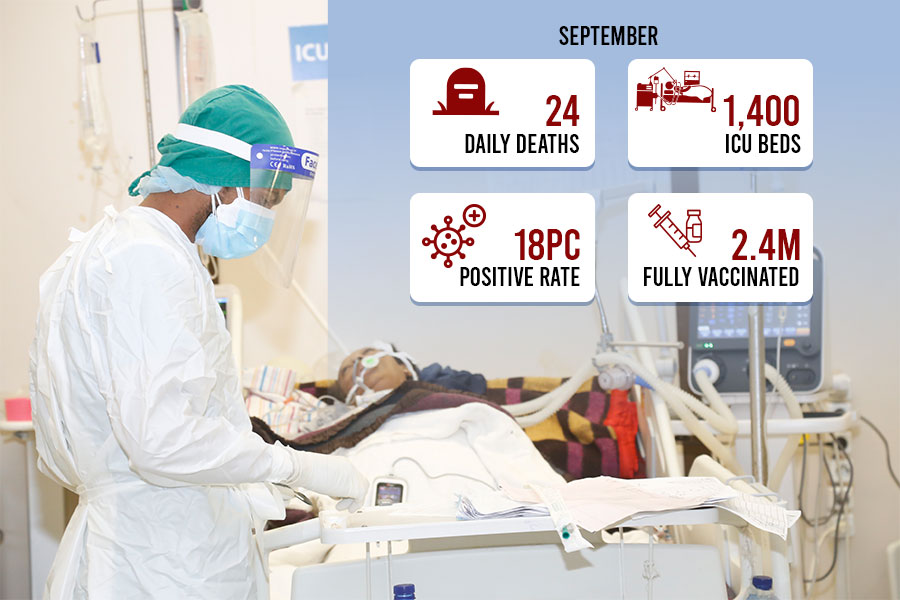

Radar | Sep 19,2020

My Opinion | Feb 23,2019

Fortune News | Jun 11,2022

Radar | Dec 24,2022

News Analysis | Jan 05,2020

Radar | Sep 10,2023

My Opinion | Oct 12,2019

Fortune News | Sep 18,2021

Editorial | Jan 25,2020

Commentaries | Jan 29,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

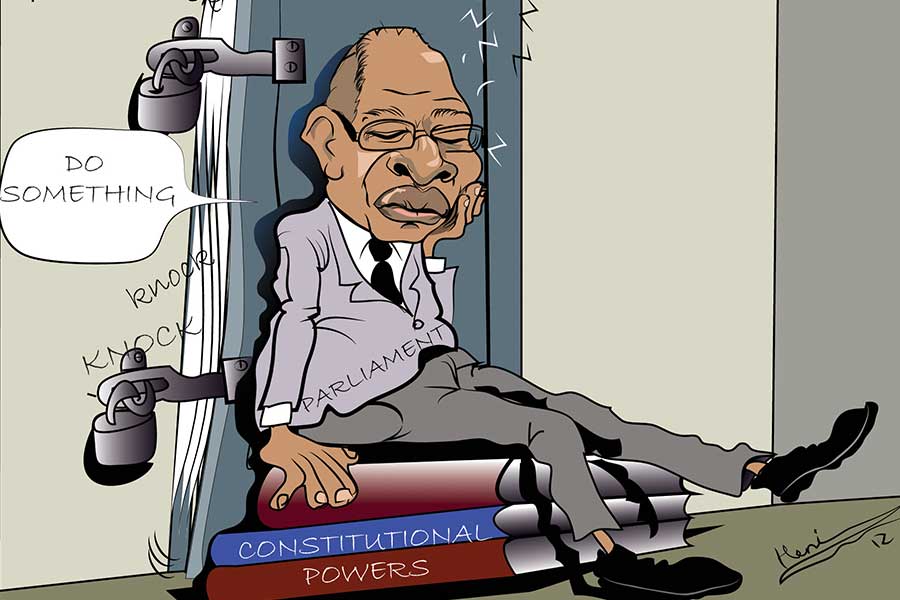

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...