Verbatim | Jun 04,2022

Sep 27 , 2025

By Abdul Mohammed

The United Nations (UN), born in the ashes of the Second World War as a mechanism to prevent catastrophe, now faces an existential question at its 80th anniversary: Can it reclaim its role as the world’s central mediator, or will it drift toward irrelevance as conflict mediation fragments into ad hoc, transactional efforts?

Eighty years after its founding, the United Nations (UN) finds itself at a difficult crossroads. It was set up in the ashes of a world war as a safeguard against disaster, a rules-based system strong enough to restrain the powerful and give voice to the weak.

Dag Hammarskjöld, one of its most respected secretaries-general, captured the spirit of the mission bluntly when he said the UN “was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell.”

But by 2025, the standard for success in too many conflicts has dropped. Now, simply announcing a ceasefire is often treated as a victory, celebrated almost as if it were a genuine peace.

This shift signals more than a mere geopolitical pessimism. It shows that the world’s collective imagination of peace is shrinking. In places like Africa, and especially in the Horn of Africa, proxy rivalries and internal fractures are more visible than ever. Here, the ideals of principled and inclusive mediation through global organisations have been replaced by short-term deals that manage violence but do not resolve the underlying problems.

Against this backdrop, the United Nations at 80 should decide whether to reclaim political mediation as its purpose, or leave the field to fast deals and “performative” peace that barely touches the causes of war.

For decades, multilateral mediation had a reputation for being the “gold standard” of peacemaking. It was transparent, authentic, and fair, and, most importantly, accountable to collective bodies like the UN Security Council or, in Africa, the Peace & Security Council of the African Union (AU). Parties to conflicts could make their case without fear. Mediators were chosen by consensus and earned the trust of all parties. Neutrality was active and principled, not passive or indifferent.

A classic example of this approach was Namibia’s transition from 1978 to 1990. The United Nations supervised the process through steady reporting to the Security Council and a commitment to self-determination, while the UN Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) closely monitored events on the ground. The result was a legitimate and accepted independence.

These early mediations primarily involved states, rather than internal factions. Governments could negotiate, enforce agreements, and deliver. Templates such as armistices, demilitarised zones, and peacekeeping missions often worked. Even when bilateral muscle made a difference, such as in the Egypt-Israel disengagements, the UN’s presence provided legitimacy and a universal frame for settlement.

By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, however, the nature of conflict underwent a significant shift. Civil wars became more common, lasting longer and involving deep identity divides, failed states, and external meddling. Mediation has become more complex, demanding greater patience and skill in building trust.

There are cases where multilateral efforts, often led by the UN, AU, or the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), succeeded in forging difficult agreements. In Mozambique, the Rome General Peace Accords of 1992 ended a brutal civil war. In Sudan, the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement brought together numerous actors to agree on new political arrangements, security structures, and wealth-sharing, paving the way for a monitored transition.

Even at its peak, however, multilateral mediation ran up against hard limits.

The conflict in Darfur from 2004 to 2008 exposed these boundaries. Fragmented rebel groups, a stubborn government, and outside powers working at cross-purposes undermined negotiations. The 2006 peace deal was seen as illegitimate by many.

The lesson was not that multilateralism could never work, but rather that mediation is always a political act, not a simple technical exercise. Success only comes when mediators tackle the root causes and power realities with craft and courage.

Today, the entire system built on multilateralism is under strain. Growing polarisation among both major and middle powers has weakened the Security Council’s authority.

In Africa, the once-promising Peace & Security Architecture has lost its momentum. The Horn of Africa now finds itself part of a broader “Red Sea Arena,” where wealthy Gulf monarchies, Israel, Türkiye, and Egypt throw their weight around with political budgets and security deals.

The new style of diplomacy is transactional in nature. Security pacts, patronage networks, and cash incentives create short periods of quiet at the expense of long-term legitimacy. The result is a fixation on ceasefires for their own sake.

Humanitarian pauses are negotiated and celebrated as though they were lasting solutions, while the hard work of political negotiation is postponed or ignored. Monitoring and verification mechanisms are thin.

In Sudan, which has faced renewed violence since April 2023, a flood of external mediation efforts, including the Jeddah talks, Egyptian initiatives, and AU/IGAD tracks, have mostly focused on achieving brief truces, which belligerents often use as opportunities to rearm and regroup.

The United Nations’ “New Agenda for Peace” recognises many of these problems. It names the dangers of proxy warfare, fragmented actors, and eroding norms. It calls for renewed focus on prevention, inclusion, and political solutions.

But the new agenda is mostly a diagnosis. Without political will and institutional courage, it risks becoming one more well-meaning document, a talking point in briefings, but not a game-changer in the field. The truth is that the model has reached its limits. The rise of complex conflicts, outside patronage, and the breakdown of old norms have outstripped the tools built for an earlier age.

If there is one lesson from the UN’s eight decades, it is that mediation is above all a political task. Technical steps such as ceasefire schedules, disarmament plans, or election timetables are important, but only if they serve a clear political strategy. The rise of “Track Two” efforts, backchannel talks and technical workshops, can be helpful for brainstorming and contact-building, but they become a problem when they substitute for political decision-making.

Former South African President Thabo Mbeki, who led mediation efforts in Sudan, argued that the mediator’s first job is to define the problem. Only by helping parties see their dispute as political, rather than as an identity or grievance, can mediators guide them to find common ground.

Political competence — knowing history, mapping power, and understanding when a “payroll peace” merely entrenches the war economy — is the vital skill for mediators. Recognising when a quick deal will fall apart due to a lack of legitimacy, and designing credible enforcement mechanisms, are essential.

Ultimately, societies themselves, not only their leaders, should be brought back into the political process, to restore respect for politics as the art of managing public affairs.

One challenge is that today’s mediators are often selected for their bureaucratic caution rather than political courage. Some avoid dealing with history and complexity. Others confuse neutrality with siding with the strongest party.

In Sudan, for example, rotating envoys and competing mediation formats have added to the confusion. In Somalia, anti-terror operations overshadowed the long-term coalition-building necessary for a political solution. A generation ago, the exclusion of the Islamic Courts movement from talks helped sow the seeds of continued insurgency.

Ethiopia, too, offers a warning about “performative” peace and the dangers of excluding key players from negotiations.

Mbeki’s point remains relevant that “Mediation is hard to initiate, harder to sustain, and hardest of all to implement.” Each stage requires political courage, strong institutional support, and patience for a process that moves slower than the news cycle.

Choosing, supporting, and protecting mediators with these qualities is not a luxury. It is the only real strategy.

Restoring effective multilateral mediation does not mean wishing for a return to a simpler, unipolar world. It means clarifying roles and rebuilding legitimacy where it matters most. Ceasefires should be seen as starting points, not endpoints. Robust monitoring, effective complaint systems, and sequenced confidence-building measures should lead the way to real political talks.

International and regional organisations, such as the UN, AU, and IGAD, should stop serving as messengers for short-term deals and instead anchor national dialogues in universal principles and inclusive processes. Where external financiers cannot be avoided, their involvement should be transparent, and subject to clear rules and verification.

Above all, mediators need to be chosen for their political skill, courage, and willingness to listen, not for their aversion to risk. Investing in the independence and training of mediators is essential.

Normative confidence should also be rebuilt. Prevention, human rights, humanitarian access, inclusion, and constitutional pathways are not luxuries. They are the load-bearing walls of lasting peace.

Hammarskjöld’s words are a sober guide for today’s unruly world. The United Nations was never meant to bring us to heaven. Its job is to keep us from hell, not by stacking up headlines about ceasefires, but by linking the end of violence to the beginning of legitimate politics.

The Horn of Africa offers a cautionary tale of how quickly “performative” peacemaking can devolve into negative peace and how easily norms are eroded when transactional logic prevails. However, it also demonstrates that with experience, strong institutions, and courageous mediators, change remains possible.

At 80, the UN faces a defining choice to be a bystander in the marketplace of politics, or to lead in forging political settlements. The outcome depends on whether international leadership can put politics back in charge, reject quick fixes, and insist that every ceasefire is a bridge to real, just, and lasting peace.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 27,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1326]

Verbatim | Jun 04,2022

Verbatim | Jun 24,2023

Viewpoints | Nov 23,2024

Sunday with Eden | Feb 25,2023

Radar | Aug 13,2022

Editorial | Jan 29,2022

Radar | Dec 19,2020

Agenda | Nov 16,2024

Commentaries | Jan 16,2021

Editorial | Jun 27,2020

Photo Gallery | 175911 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 166127 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 156537 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136852 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

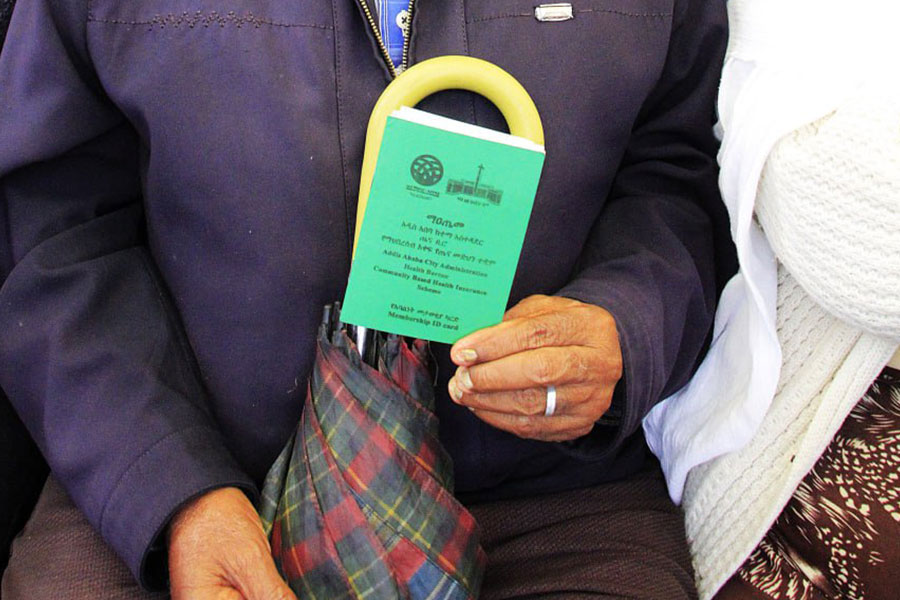

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...