Fortune News | Jan 01,2022

Established over two decades ago when a handful of businesspeople were interested in joining the construction industry, Afro-Tsion Construction Plc started a business with a capital of 50,000 Br. Today, this won't buy a high definition 55-inch television, let alone run a grade-one construction company.

As time went by, Afro-Tsion became a company to be reckoned with in an industry that turned out to be the fastest-growing segment of the economy, contributing nearly a fifth of the country's GDP. It was a remarkable growth from the mid-1990s when the construction industry's share of the GDP was just a mere five percent. Courtesy of the industry's impressive growth in the last decade, Afro-Tsion had been one of the major players, recognised by those at the top echelons of government, who rarely missed inaugural events.

Founded by its major shareholder, Sisay Desta, the firm recorded 201 million Br in capital when it was reentered into the registry in 2012.

Despite enjoying decades of success and praise, however, the last three years have been all but gratifying for the construction firm, which currently handles 25 projects with a total value of nearly 11 billion Br.

The war in Tigray Regional State has forced it to suspend operations there, where Afro-Tsion has four projects and properties estimated to be worth half a billion Birr. The construction industry has been experiencing a slowdown following the outbreak of COVID-19. Afro-Tsion received termination notices for four of its projects in Addis Abeba and Adama, while an additional three projects have received serious warnings. The remaining are dragging along at a snail's pace.

"Undeniably, we are in trouble," Laychluh Mechegiaw, general manager, admits.

So are the financial institutions providing guarantee bonds to the construction companies in the deep water. Coupled with years of failed and incomplete construction works, the unexpected fall of construction companies, especially those with grade one licenses, has brought what could very well be a substantial risk to banks and insurance firms.

Afro-Tsion has recently placed four commercial banks in hot water. The Federal Government Building Construction Project Office has claimed 451.5 million Br from Wegagen and Berhan banks for guarantee bonds issued for public projects plucked from under the company's feet. Bunna and Enat banks are also in a squeeze for bonds they made out to Afro-Tsion to construct an Ethio telecom office in Adama (Nazareth) and Bole General Hospital, a project under the Addis Abeba City Health Bureau.

These projects have a combined cost of a little over two billion Birr.

Afro-Tsion is hardly alone in this, a trying time for the construction industry. The Project Office has also terminated contracts with Tekleberhan Ambaye Construction Plc (TACON) and Beha Construction Plc for projects in the capital, again exposing Enat and Berhan banks to over a quarter of a billion Birr in advance payment guarantee bonds.

These are part of the 15 major public projects whose contracts terminated out of around 794 commissioned by the state.

Several commercial banks headquarters are under construction in the neighbourhood of Senga Tera, Addis Abeba, giving the area its new moniker: the "Financial District."

Project owners, which usually shell out to contractors advance payments amounting to 20pc and 30pc of the total project cost, have justifications for lodging claims on the financial institutions. They provide guarantee bonds pledging that they would make the payment upfront if the contractor fails "on the client's first notice, irrespective of anything."

The financial institutions are tempted to take such a daring risk for the 1.5pc commission they collect to provide the guarantee, a seemingly small amount compared to the trouble facing them now. It is customary though, for grade one contractors to work on projects that might have a combined cost of 12 billion Br at a time.

Ermias Andarge, president of Enat Bank, concedes that most banks do not find assets to take as collateral in exchange for advance payment guarantee bonds, which could reach three billion Birr. Nevertheless, the contractors manage to receive bonds from banks and insurance companies. Their reputation, volume of works, the magnitude of projects they win, and previous experiences are what the banks consider before they issue bonds. However, they overlook contractors` expertise, financial and managerial capacity, record in completing projects, and the project's feasibility, according to a senior bank executive.

“Their focus is revenue-driven," says this executive. "The banks write guarantee bonds to anyone who asks them without measuring risk. They are themselves liable for whatever follows.”

Hardly any of the risk considerations, investigation, and collateral used in loan provision is employed with guarantee bonds. Insurance companies are also guilty of these oversights. They were in crisis in the mid-2000s for a series of defaults from clients who took "unconditional guarantee bonds" until authorities at the central bank brought an end to the practice, with the stroke of a pen.

Kassa Lisanework has been the CEO of Tsehay Insurance for over seven years. He admitted that the mishandling of guarantee bonds in the financial sector and acknowledged the irregularities his firm has faced. Tsehay was one of a handful of companies delisted by the Ethiopian Roads Authority (ERA) after defaulting on 40 million Br for guarantee bonds issued on two contractors' behalf.

“We don't demand collateral from grade one and grade two contractors; it's their reputation and profile we check,” Kassa told Fortune. “It's mainly the business linkage we aspire to leverage as providing guarantees would give us a competitive edge to cover other properties.”

It appears that the insurance companies are facing less risk, however, for their risk is often shared with reinsurers.

The conundrum, according to many in the industry, does not stop here. The public procurement policies and regulatory work are as much problem, leading to many public projects stalled.

Mesfin Negewo, director-general of the Construction Works Regulatory Authority, attributed many of these contracts to "improper awards made three years ago."

What lays behind this "improper" practice is the government preference for the "least bidder is the winner" policy, says Abebe Dinku (PhD), professor of civil engineering and board chairperson of Zemen Bank. Instead of selecting the most responsible and competent bidder, this policy encourages cutthroat competition in the industry.

"This should be checked and changed,” Abebe told Fortune.

Mesfin admits that the "least bidder is the winner" has many flaws, including substandard works and failure to take into account cost escalations during the project's life.

“We're counting on different solutions such as subcontracting projects, adjustment on prices to ease cost escalation, and making regulatory changes,” Mesfin told Fortune.

It was not like this until the construction procurement policies changed a decade and a half ago. Back then, a bidder would have been automatically dismissed if offered 20pc lower or higher than the project cost made by the consulting firm.

The government hopes to see the construction industry create 3.3 million jobs in the next decade. But it is an industry besieged by a web of constraints such as cost escalation, forex shortage, lack of financing, and cash flow problems. However, contractors' self-imposed problems such as maladministration and incapacity in project management play a part, according to Aisha Mohammed, minister of Urban Development & Construction, speaking at a conference last year.

Besides contractors offering the lowest bids in their desperation to win contracts, discipline in using advance payments for the intended purpose is lacking. Many of the construction companies have side businesses such as real estate that are poorly managed. Contractors often use advance payments made for new projects to pay for outstanding bills on previous contracts. When new contracts dry up, ongoing projects suffer. For many, it is a circular process.

Haben Abraha, a construction engineer with over a decade of experience, has observed a common practice in the construction industry. He believes it is not healthy and does damage the reputation of an industry where the domestic firms are poorly represented.

“Payments from one project should never be used for other purposes,” said Haben. "Contractors need to have a strong financial management system."

Mismanaging project payments and funds is a major issue, Laychluh of Afro-Tsion Construction admits.

The incapacity, poor project managment and maladministration in the construction industry are harming those in the financial sector.

The President of Enat Bank sees the growing malaise as a "national problem" poisoning the broader economy. If the banks and insurance firms go down, so will the macroeconomy tatters.

"A government bailout can be considered an option,” Ermias of Enat Bank told Fortune.

For Abdulmenan Mohammed, a financial analyst based in London, government intervention should depend on the size and significance of the institutions at risk.

“If the bonds issued are much bigger than their financial capacity, the matter might entail the intervention of the government in the form of bailout or other means,” Abdulmenan said.

Others in and outside of the financial sector disagree.

“I don’t think bailing them out should be an option," said the senior bank executive who spoke to Fortune. "The banks should be made to pay and learn from their mistakes. This should serve as a wake-up call for all the banks, even for those that are not affected.”

According to Abebe, forcing the banks and insurance companies to make the payments is the right course of action. He believes the financial institutions are a major part of the problem in providing guarantee bonds without holding collateral.

There is hardly a consensus on the way forward. From Abebe's recommendation to limit advance payment to 10pc of the project cost at a time to Abdulmenan's advice for the central bank to conduct investigations over allegations of malpractice, suggestions abound.

No less than six of the 19 banks have their executives in discussion with officials of the Construction Works Regulatory Authority, while insurance firms await approval from the central bank of a threshold rate for bond and guarantee policies – a measure which they hope will fix the mess.

Regulators at the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) have yet to take any serious measures, leaving the issue in the hands of the banks.

Using their own terms and conditions, the banks should make the contractors liable for the bonds they issued, according to Frezer Ayalew, director of banking supervision of the NBE. It seems inevitable Afro-Tsion's managers would hear from their banks and insurance companies soon.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 11,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1106]

Fortune News | Jan 01,2022

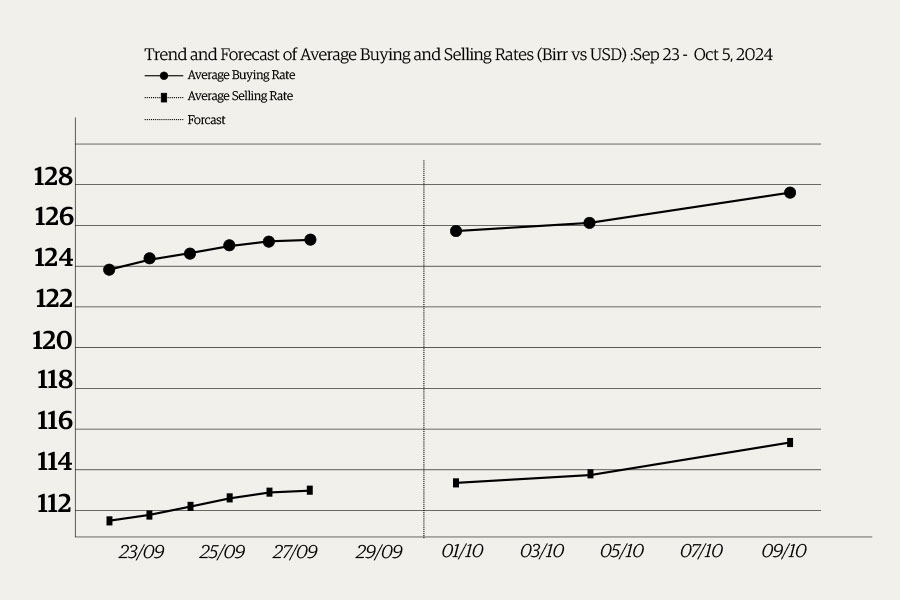

Money Market Watch | Sep 28,2024

Sunday with Eden | Dec 19,2021

Fortune News | Aug 20,2022

Radar | Nov 03,2024

Radar | Jun 19,2021

Fortune News | May 26,2021

Fortune News | Aug 28,2021

Fortune News | Nov 06,2021

Fortune News | Jul 13,2019

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...