Bole Airport Area Residents' Idir members gathered at a consumer association cafeteria around Cape Verde St for their monthly meeting. What began as a routine gathering turned into a storm of confusion and concern, as a representative from the Women & Children's Bureau disclosed a directive that would fundamentally change their association. Traditionally a purely social organisation, their Idir would now be integrated into a formal hierarchical structure under the Bureau.

The Chairwoman of the Bole Airport Idir observed the confusion among members. Their 50-year-old Association, comprising over 200 households, faced a different future that requires financial audits and imposes social development responsibilities. This announcement caused a stir among the members, leading to an abrupt end of the meeting.

One attendee, Yetifwork Wolde, a 70-year-old who has been part of the Idir for 40 years, was particularly confused. "I didn't understand anything," she said. "It's as though we are turning into something else." For Yetifwork, joining the Idir was about maintaining social bonds and cohesion. She recalled the support she received during her toughest times, especially after losing close family members. "It's what got me through," she told Fortune.

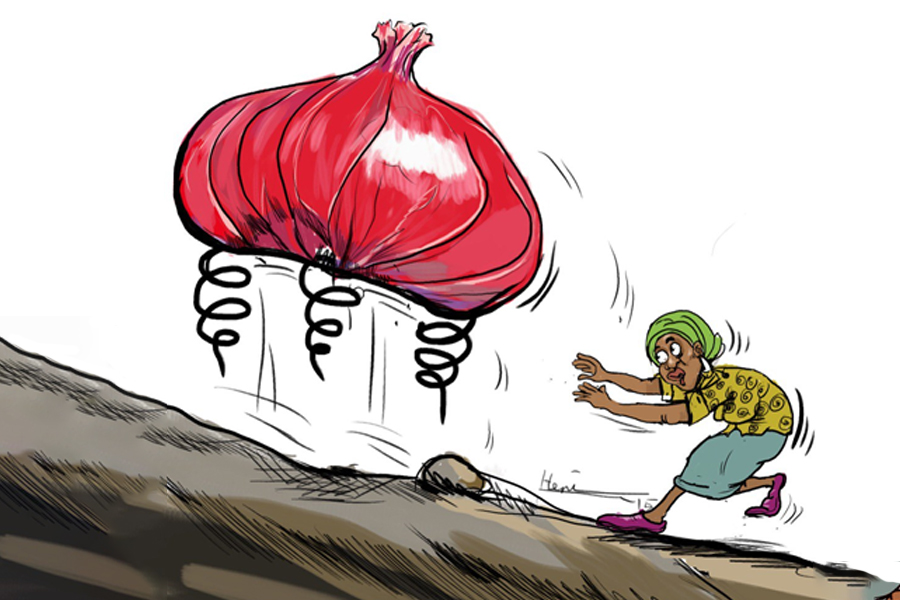

Historically, Idirs have been grassroots social safety nets, primarily providing mutual aid for burials and addressing other community needs. However, their relevance has declined over the years, with the evolving urbanisation and outsourced funeral services in the capital. This decline prompted the Addis Abeba Women, Children, & Social Affairs Bureau to take action.

Signed by Woinshet Zerihun, head of the Bureau, the government has decided to regulate these associations by integrating them into its structure. Officials envisioned forming Idir councils at administrative levels and ensuring regular financial and social activity reports.

According to Genet Kitaw, deputy head of the Bureau, formalising Idirs was not just about control, but about boosting their potential. She believed these associations held major financial resources that could serve a wider range of purposes than solely funding funerals. She said restructuring to improve financial management and ensure the long-term sustainability of these associations for future generations is the goal.

"Gaps in finance management will be addressed," she said.

The vision for the future of Idirs was not simply financial. The Bureau had conducted a two-year assessment of these associations, identifying areas where they could improve their community contributions. Their plans included expanding the roles of Idirs to register births, deaths, marriages, and divorces in cooperation with Civil Service Registration & Residency Service Agency. This new role, Genet believed, would allow Idirs to play a more significant role in the community.

"Real changes can be made," she said.

Her optimism was supported by research conducted by Dejene Aredo. His findings show the reasons behind the enduring popularity of Idirs compared to the insurance system. He identified factors like cultural appropriateness, flexibility, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness as key reasons for their continued appeal. Dejene's research also sheds light on the informal sector's potential evolution into a complex and well-organised financial system. He emphasized the inherent self-adjusting mechanisms Idirs possess, allowing them to adapt to changing circumstances. According to him, these strengths should be acknowledged and supported by government policies to gradually transform these existing traditional financial institutions into modern ones.

Despite the compelling arguments for reform, the Bureau's directive wasn't met with universal acceptance. While over 7,150 Idir associations had already registered and received licenses under the new structure, this represented only a portion of the estimated 10,000 associations across the city. There were concerns and resistance, particularly about the level of government involvement.

Idirs have long existed as informal institutions with socially shared rules, sometimes unwritten. The rules are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels. The voluntary association has been the most widespread form of Idir, but its composition, system, approach, and size differ from place to place.

This informality, however, presented challenges for the Bureau's plans. Bole District, for instance, comprises around 600 associations currently in transition. Tarekegn Negasa, a senior expert at the District's Women, Children & Social Affairs Bureau, acknowledged the ongoing struggle to raise awareness among members. He explained that several meetings were being held to address these concerns. Despite these efforts, resistance persisted, particularly regarding the Bureau's control over finances.

"People need time to come to terms," he said.

Arada District seemed to be experiencing more success. Around 250 associations there had been registered in the past few weeks through its weredas. However, challenges remain where residents have been displaced by development projects, further straining their resources.

According to Tesfanesh Besufikad, head of the District's Women, Children & Social Affairs Bureau, discussions with members revealed both potential benefits and lingering doubts. Tesfanesh acknowledged the need to address the financial limitations of some associations as many members belong to the lower economic class.

"Different social activities would be required to help them become financially self-sufficient," she said.

Research provided some insights into how these financial limitations could be addressed. Studies suggested that Idirs, placed in a more supportive environment, could become active partners in promoting social protection and grassroots development. Their strong foundation in the community, built on trust, made them ideal candidates for such collaboration.

Experts believed that by recognising Idirs' potential role as civil society representatives, the government could unlock significant contributions in these areas. However, this vision did not apply uniformly. The financial reality of Idirs differed greatly depending on location. In more affluent neighbourhoods, Idirs possessed substantial funds and operated with their own set of rules, completely independent of government organisations.

The Bureau's directive aimed to encourage all Idirs, regardless of wealth, to embrace new practices. These included saving money, investing, and even engaging in income-generating businesses. Addis International Bank has been at the forefront of this initiative since its inception 14 years ago, with over three percent of its shareholders constituting Idirs.

Social ties are another area that worries members.

Meseret Yitube, chairwoman of the Lebu Sisters' Idir Association, understood the potential of Idirs to foster solidarity and community. Her 14-member association, comprised of households around Garment, served as a financial safety net during difficult times, particularly for funerals. However, Meseret worried that the pandemic had already weakened these connections, and she feared further strain if Idirs became too bureaucratic.

"It was one way to bring us together," she said, reflecting on the pre-pandemic closeness. She was unsure if the new structure would strengthen or dilute this social bond.

Meseret's concerns resonated with many Idir members. While acknowledging the potential benefits of expanding Idirs' roles, she also expressed a common fear: a loss of the association's core social function. This apprehension was further highlighted by Mekdes Mamo, chairperson of another Idir association nearby. Mekdes' association, with 45 members, had been around for over a decade, and she believed their purpose extended beyond just funerals. However, she worried that increased financial requirements under the new structure could discourage participation.

A past membership fee increase from 30 Br to 100 Br had already caused friction, and Mekdes feared that becoming a government entity could lead to a loss of the association's autonomy and its heart.

"I am afraid things won't be the same," she said, echoing the anxieties of many members.

Despite the anxieties, experts saw promise in the Bureau's initiative. Kibur Engidawork (PhD), a sociologist, recognised the long-standing role Idirs played as a safety net during challenging times. He emphasised the trust these associations held within communities, showing their potential to make contributions to social development projects beyond funerals. He recalled their crucial role 20 years ago in mitigating the spread of HIV through educational campaigns.

Kibur supported the idea of regulation to prevent misappropriation of funds, given the substantial capital some Idirs possessed. However, he cautioned against excessive government control, which could lead to resistance and a decline in participation. He advocated for open communication and awareness campaigns before enforcing stricter regulations.

"They will need help to evolve into viable organs," he said.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 21,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1264]

Fortune News | Aug 06,2022

Life Matters | Aug 25,2024

Radar | Apr 15,2023

Fortune News | Mar 16,2024

Viewpoints | May 31,2025

Verbatim | May 06,2023

Advertorials | Aug 02,2025

Fortune News | May 27,2023

View From Arada | Aug 13,2022

Editorial | Sep 16,2023

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...