Fortune News | Jun 24,2023

The Addis Abeba Trade Bureau is piloting a digital tracking system to tighten surveillance over the distribution of essential commodities whose prices are subsidised by the state.

Steered in two weredas of Kolfe Keraniyo District, city officials hope the system can help allay disruptions and shortages burdening consumers. The federal government began making essential consumer items such as wheat flour, cooking oil, and sugar directly available to consumers in 2011. The regional trade bureaus have been distributing the commodities at subsidised prices through consumer unions comprising cooperatives.

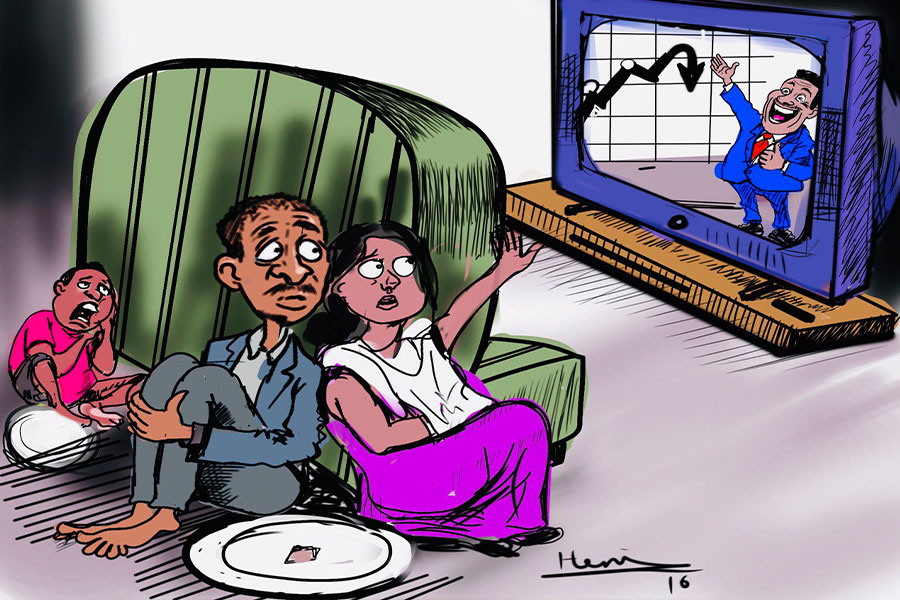

There are 11 unions in Addis Abeba with 140 cooperatives, selling 1.4 million quintals of sugar, 1.9 million quintals of flour, and 90 million litres of edible oil annually. Households are allotted up to five kilos of sugar and five litres of cooking oil a month. The distribution process has, however, remained woefully inefficient despite murky explanations. The inadequacies become more transparent as the cost of living continues to spiral, leaving millions of residents more dependent on the subsidised goods.

According to the Ethiopian Statistics Service, year-on-year headline inflation registered at 33.6pc in February, above the 30pc mark for the seventh month in a row. Food items saw 41.9pc in consumer price index compared to the preceding February 2021, as cereals including teff, wheat and maize exhibited significant price jumps.

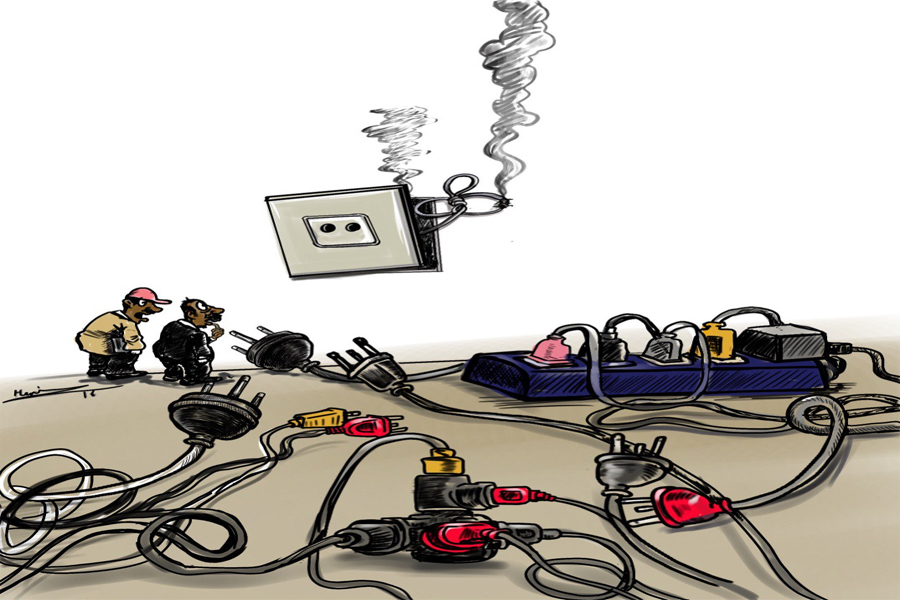

Sugar and cooking oil have disappeared from shelves as the market is overwhelmed by a slew of challenges, from inflation and the ever-present forex crunch to the COVID-19 pandemic and political instability. The war in Eastern Europe has exacerbated the situation, driving up international prices for crude oil, fertiliser and wheat, essential items imported to Ethiopia.

City officials sought a digital solution for the problems.

Daniel Mieassa, director of public relations for the Addis Abeba Trade Bureau, sees the inefficient distribution system as a major factor behind the shortages, besides the imbalance between demand and supply. He disclosed the administration had been challenged in ascertaining whether commodities make it into the hands of consumers.

The problem is not new. The Bureau had introduced a coupon-based system two years ago, hoping to modernise distribution systems and fight illicit trading. The coupons have had little impact. The Director blamed diversions of commodities from the formal distribution channels and sold elsewhere.

The Bureau has chosen Makiba General Trading Plc to deploy the digital tracking system. The company was selected after it submitted a proposal last year.

Incorporated four years ago with 16,000 Br in capital, Makiba Trading has previously supplied sanitary products and other items to cooperatives. It has been monitoring the gaps in the distribution channel for the last three years, according to Awash Mohammed, general manager.

The company has developed mobile applications in-house to facilitate registration, delivery and payment under the pilot programme. Development and deployment have thus far cost the company 5.2 million Br, according to Awash. Makiba makes use of Agelgel, a delivery company operating under it, to deliver the food items door-to-door using an app. Since the pilot project kicked off four months ago, it has registered close to 14,000 users in its database, delivering sugar and cooking oil to close to 6,000 consumers.

Experts such as Tewodros Tadesse, chief executive officer (CEO) of xHub Addis, a startup incubator, applaud the initiative to turn to digital to solve problems. But he warns that this won't be enough to subdue the trouble.

"Improving agricultural productivity is essential to deal with the shortages," said Tewodros.

City officials blame illicit trade for the widespread shortages observed in the supply chain.

"Illegal traders create artificial shortages to drive prices up and benefit from it," said Daniel.

An assessment conducted by Makiba two months ago revealed that clumsy distribution is more to blame for the shortages than supply-side problems. The company identified 6,000 consumers as beneficiaries in one of the weredas, though cooperatives claimed the number is closer to 9,000. The company had to return nearly half of the 400qtl of sugar it had received for distribution, according to Awash.

Makiba receives a kilo of sugar for 33.68 Br, selling to consumers for 35 Br. It has hired 25 employees to facilitate its door-to-door delivery service.

Among the 1.2 million Addis Abeba residents eligible to buy essential goods at subsidised prices is Nigist Afework, a mother of three. Since its inception, she has been dependent on the subsidy scheme but has struggled to buy essential goods lately. Makiba staff deliver commodities to her.

“Although the commodities are available sometimes, it's difficult to buy due to the long queues,” she told Fortune.

Last week, Nigist had five kilos of sugar delivered to her door.

For now, consumers like her are limited to paying in cash or through PoS machines for the commodities. This will change soon when negotiations with private banks are concluded, disclosed Awash.

The Trade Bureau will decide to deploy the system entirely after the pilot project is concluded in the coming May.

“If the system proves successful, it'll be deployed in the remaining districts,” Daniel told Fortune.

PUBLISHED ON

[ VOL

, NO

]

Fortune News | Jun 24,2023

Radar | Jul 07,2024

Radar | Dec 12,2020

Fortune News | May 15,2021

Fortune News | Jul 15,2023

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transportin...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

The cracks in Ethiopia's higher education system were laid bare during a synthesis re...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Construction authorities have unveiled a price adjustment implementation manual for s...

Jul 13 , 2024

The banking industry is experiencing a transformative period under the oversight of N...

Jul 20 , 2024

In a volatile economic environment, sudden policy reversals leave businesses reeling...

Jul 13 , 2024

Policymakers are walking a tightrope, struggling to generate growth and create millio...

Jul 7 , 2024

The federal budget has crossed a symbolic threshold, approaching the one trillion Bir...

Jun 29 , 2024

In a spirited bid for autonomy, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), under its younge...