Over a cup of coffee with a friend, I had a “mathematical” talk. It all started with her elation after her young daughter’s success, a student of medicine now. This was enough to make her elated, one may think. Yet, it was the fact that her daughter had progressed in a field (medicine) that was far enough from a subject that she deeply detested, mathematics.

The mother’s grades in mathematics started out promisingly, only to become elusive as she progressed to high school. She said that it made her hate everything about school. The idea of math tests sounds nightmarish to her now.

That, in its turn, took me back to my high school days. After finishing the eighth grade, we enrolled at Black Lion. It was a year the revolutionary fervour started to subside and many youths returned to school. The small-sized school was forced to go three regular shifts to accommodate the tide of almost all ninth-grade students. Each classroom was crammed to its utmost.

Just as we started the semester, to our dismay, our mathematics teacher gave us a test. The results were grim for many of us. As he finished disclosing the results, based on our address from a list he held, he firmly declared that the overall result corresponded to where we lived. Almost all who did well came from the southern direction of our school. Though dismayed with his assertion at first, it did not take us a while to figure out why exactly those students did better.

It was because they were from Felege Yordanos and Agazian, two private elementary schools nationalised after the Ethiopian revolution. Yet, it was only the ownership that changed hands, not hearts. The two ex-owners were retained as directors of the schools. It was crystal clear that students from these schools had a strong attachment to mathematics. It also built their mindset to follow up with confidence the other subjects.

For the rest of us, it was not that easy. It was no different for me as I had sought to form friendships with backbenchers. It was not easy to win the hearts of back-seating friends, many of them our age seniors.

We were around ten in number from our neighbourhood walking to school together. It was when tea houses were popular in Addis. It was there where we met to go to school, though it was a struggle to find coins for tea and biscuits. We started to meet early first and then to frequent Andinet Tea Room of Senga Tera, which came in handy to tolerate our penny-less group, which assembles with a single obsession – mathematics.

Our start was reminiscent of the rocky mathematical road. It all started well, with Amharic being its instructional medium. In our public school, there was only one qualified teacher. His temper changed as the medium turned to English, as we started to struggle with the additional burden of the language. We had a complete doubt over the relevance of “X” and “Y,” with the slowly but surely creeping Greek and Latin terms in our lives.

Yet, thanks to our patience and perseverance, unlike many of our friends who dropped out, we survived by closing the gap. This, thus, resized our number. Maths was the great in-equaliser. How impressive it was to come to school then – much of our arguments started with mathematics, as it was very easy to reason and prove, then expand to other subjects.

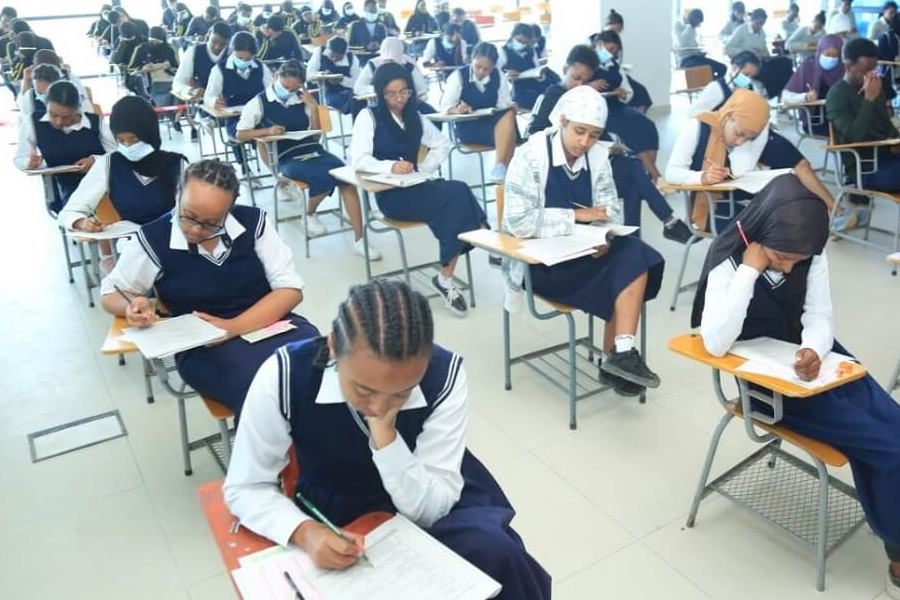

It continues to be hard to convince school kids of mathematics’ relevance in relation to sorting out real-world problems. But the country of tomorrow requires a labour force that can at least read data and categorise and gather insight from patterns. We need students fluent in the “grammar of mathematical discourse,” not just for the sake of creating more engineers but even for the likes of medical students.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 01,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1131]

Radar | Jul 15,2023

Fortune News | May 24,2025

Life Matters | Jun 15,2019

Delicate Number | May 17,2025

Life Matters | Apr 22,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...