Photo Gallery | 157034 Views | May 06,2019

Sep 13 , 2025. By Raid Mohammed Adem ( Raid Mohammed Adem is a public health and development researcher based in Addis Ababa who writes on political economy and development issues in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. He can be reached at (raidmohammedadem@gmail.com) )

The federal government secured over 3.4 billion dollars in foreign exchange reserves after years of support from global lenders and a one-time payment from the Safaricom consortium’s telecom license. However, it covers only 1.6 months of imports, below the three-month safety-net economists recommend. The injection of cash from Safaricom was seen as a game-changer. But, infrastructure projects slowed, setting a new tone for growth in the capital and beyond.

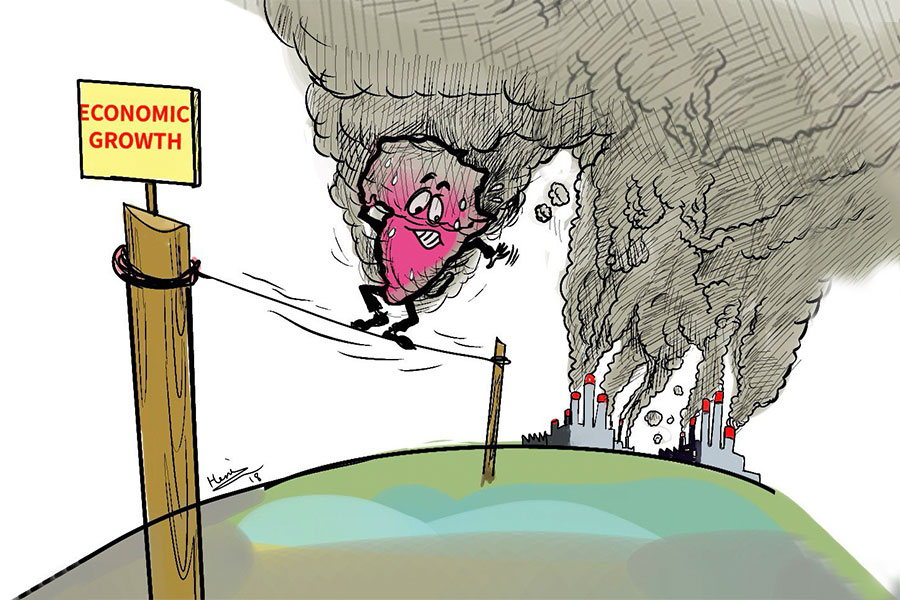

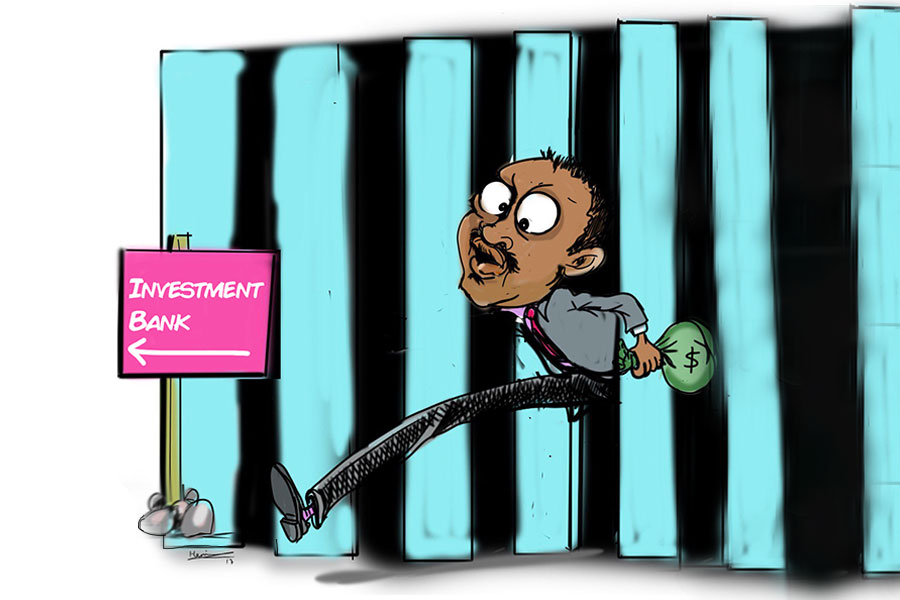

After drawing billions of dollars from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and bilateral lenders, and pocketing a windfall from Safaricom’s telecom license, Ethiopia finds itself on a fragile economic footing, with little fiscal room to manoeuvre and a public worn down by hardship.

The money trail starts not with loans but with the war. When the Safaricom consortium paid its license fee, Addis Abeba received a rare injection of foreign exchange. However, the officials chose to allocate a large portion of the forex reserve to pay for mounting military costs. Resources drained away, public services suffered, and growth stalled, setting the stage for another rescue.

By the time Ethiopia sought help from the IMF and the World Bank, the fiscal and reserve positions were battered. The lenders stepped up, but on conditions. The authorities were compelled to float the Birr, widen the tax net, trim public spending, and privatise state assets. The checklist, lifted from a familiar neoliberal manual, was presented as the ticket to modernisation. In reality, it opened new fault lines while leaving old ones intact.

In early 2018, when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) took office, the forex reserve was between 3.36 billion dollars and 3.98 billion dollars. Six years on, several conflicts, multiple loan tranches later, and with the IMF program, as well as support from the World Bank, the amount neared 3.4 billion dollars. Import cover remains stuck at about 1.6 months, well below the three-to-six-month buffer most economists deem prudent. Outside cash averted collapse, but it did little to improve Ethiopia’s ability to pay for imports or defend its currency against shocks.

Institutional credibility has eroded alongside the reserves. Mamo Mihretu, the former governor of the Central Bank, resigned this summer after repeatedly telling lawmakers that the economy was “healthy and stabilising,” even as the cost of living remained stubbornly high, reserves stagnated, and the Birr sagged. His exit unsettled an already wary public. Mamo had been a chief architect and defender of the policies that papered over trouble with borrowed calm.

Currency strategy tops the list of concerns. The Birr was floated before the Central Bank had stockpiled the dollars needed to manage swings. Depreciation quickened, and officials now vow to crack down on dealers in the parallel market. Enforcement may slow speculation, but a flexible rate works only when the Central Bank can back its words with cash.

To meet debt-service bills and satisfy IMF benchmarks, the government has pushed tax collections sharply higher. Small businesses carry the burden of frequent penalties, while audits are choking them out of business. Meanwhile, inflation keeps eroding real wages. In Addis Abeba and other cities, families wrestle with paychecks that lag behind food and rent. The simultaneous squeeze on shops and households is ill-timed for an economy that needs investment and consumption.

Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate economist, in his book titled “Back to Depression Economics”, warns that austerity in a downturn is a recipe for disaster.

Equally troubling is what the state has stopped doing. Before 2018, even a debt-laden government poured money into roads, power lines and railways. The projects created jobs and expanded productive capacity, though they enlarged the debt pile. Today, many big public works have stalled, replaced by cosmetic urban makeovers with marginal economic returns. The opportunity cost is steep, as neglecting productive investment risks locking the economy into a slow-growth trajectory, thereby leading to chronic dependence.

Not acknowledging the wider issue where international loans are not charity, for they reshape domestic policy and affect sovereignty. Ethiopia’s embrace of privatisation, austerity and a floating currency was less a free choice than a condition for fresh credit. Every borrowed dollar narrows the federal government’s freedom to steer its own development path, trading national strategy for external orthodoxy and leaving officials with less room to shelter citizens from hardship.

That trade-off is becoming visible on the street. Retailers complain that higher taxes and shifting exchange rates make pricing impossible. Manufacturers who import machinery are never sure they can secure dollars when payments come due. Parents tallying the family budget watch staples climb from one week to the next. The burden lands hardest on urban wage earners and the small businesses that employ them.

Stability bought with debt at the expense of autonomy is unstable by definition. Ethiopia needs a plan that pairs outside funding with domestic priorities, one that channels scarce foreign exchange into factories, farms and essential services instead of the next military campaign. It means reviving infrastructure that yields long-term returns, loosening the tax vice on entrepreneurs and protecting household purchasing power while inflation is tamed.

Economic policy, after all, is about more than pleasing lenders or balancing spreadsheets. It is about safeguarding livelihoods and building resilience against shocks that will, sooner or later, test the system again. Ethiopia’s leaders often talk of becoming a regional manufacturing hub and a middle-income country. Neither goal will be met if the fiscal foundation rests on borrowed sand.

If the current course persists, the country risks cementing a cycle of debt, dependency and discontent. And with every month that passes, the cost of delay compounds, eroding confidence among investors, partners and citizens the reforms claim to serve. The task now is to trade illusion for real strength, to replace quick fixes with a strategy that puts Ethiopian priorities first, before the picture dissolves completely, with or without the departure of its most visible defenders.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 13,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1324]

Photo Gallery | 157034 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 147325 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 135901 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 135290 Views | Aug 14,2021

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...