Sep 13 , 2025. By Abdul Mohammed ( Abdul Mohammed (bati101@gmail.com) is a former senior AU and UN official with extensive experience in mediation in the Horn of Africa, particularly in Sudan and South Sudan. He served as Chief of Staff and senior political adviser to the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel for Sudan, South Sudan, and the Horn of Africa, chaired by former President Thabo Mbeki, and most recently as Head of Office of the UN Special Envoy for Sudan. This article first appeared on www.boell.de and is republished here with the author's consent. )

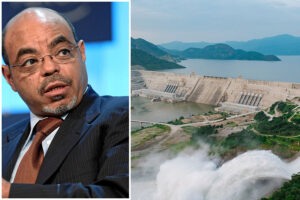

Meles Zenawi, who died in 2012, never saw the turbines spin. However, his vision of a dam built on the Nile River outlived him. Successive leaders, including Hailemariam Desalegn and Abiy Ahmed (PhD), carried the project through a period marked by unrest and shifting alliances. Their persistence should serve as a sign of a rare thread of policy continuity in a region where abrupt change is the rule, not the exception.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) stands today as a wall of concrete, steel and national determination, an enterprise so audacious that many outsiders once doubted it would ever rise from the Blue Nile’s remote canyon. However, rise it did, and the giant reservoir it creates, with tens of millions of cubic meters of fresh water spreading across a highland frontier, offers a potent reminder that the political will of a single leader can redraw the landscape and expectations.

That leader was Meles Zenawi. Without his covert planning, relentless persuasion and stubbornness not to accept foreign vetoes, there would be no turbines spinning today and no lake waiting for an official name. In word and in deed, Ethiopians would welcome a decision to name the reservoir "Lake Meles Zenawi," honouring the man who first dared to pull the Blue Nile into the country's economic bloodstream.

Every Ethiopian ruler since Emperor Haileselassie spoke of taming the Nile’s upstream power. It was only Meles who succeeded. Egypt, dependent on the River for agriculture and drinking water, long declared the Nile its “private preserve,” pressuring lenders such as the World Bank and USAID to steer clear of any Ethiopian design that might siphon a drop. Meles met that resistance with stealth. Detailed blueprints were drafted in-house, on a need-to-know basis, to keep hostile eyes at bay.

When Western capital predictably stayed away, he turned to millions of ordinary citizens, asking them to fund the project through bond purchases and voluntary salary deductions. It was an unabashedly patriotic appeal, and it worked. From villagers to civil servants and diaspora entrepreneurs, millions of Ethiopians bought stakes in a dam they had never seen, convinced that self-reliance was the surest insurance against meddling.

Meles also crafted a diplomatic frame that cast the project as a gain for all three major Nile riparians. To Sudan, he pointed to moderated flows that would end the seasonal floods wrecking irrigation canals and fields; Khartoum could dream of reclaiming vast stretches of arable land and becoming, in his words, “the breadbasket of the region.” Egypt, he argued, would lose less water to evaporation once the Nile exited the highlands in a steadier and calmer stream.

“Predictability,” he told visiting delegates, “is security.” That logic resonated beyond the Nile Basin. The African Union (AU) later placed the Dam on its flagship Agenda 2063 list, branding it evidence that Africans could finance and manage transformative infrastructure on their own terms.

The story, of course, did not end with Meles’s death in 2012.

Former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn inherited a half-built dam and a restive political climate, yet kept construction crews on schedule. His calm and low-profile stewardship bridged a potentially dangerous vacuum. In 2018, Abiy Ahmed (PhD) took office, facing a raft of internal reforms and regional tensions. He, nonetheless, shepherded the final civil works, pressed the button for the first test of the turbines and welcomed the initial surge of electricity onto the national grid.

Each leader, in his turn, advanced an agenda conceived by Meles and thereby consolidated a rare through-line of policy continuity in a region better known for abrupt course changes.

Meles’s imprint on Africa extended well beyond hydropower. He spearheaded the transformation of the moribund Organisation of African Unity (OAU) into the African Union (AU), arguing that the continent needed more authority, sharper technical bodies and the confidence to police its own crises. He backed the creation of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) to knit economies together and reduce reliance on commodity exports. When climate negotiations unfolded in global arenas, it was often Meles who articulated Africa’s unified position, warning richer countries not to treat the continent as a collateral casualty of industrial emissions.

Meles's passing drew eulogies from heads of state who acknowledged that he spoke for a generation seeking growth without apology.

Yet the GERD, more than any speech or summit communiqué, fixes that legacy in concrete. Engineers say it has a capacity of more than 5,000MW, enough, when fully operational, to double the existing output, and will reliably electrify factories and homes from Addis Abeba to remote villages where kerosene lamps still glow at dusk. Sudanese agronomists eye predictable river levels and calculate crop cycles that could feed markets from Port Sudan to Juba. Even Egyptian hydrologists, once uniformly scornful, concede that the Dam’s staged filling has so far avoided the catastrophic shortages Cairo once feared.

Meles preached cooperation, not confrontation, and the early evidence shows he may yet be proved right.

However, the realisation of those benefits depends on peace, an increasingly scarce commodity in the Horn of Africa. Sudan’s civil war has paralysed agriculture in the very fields GERD was expected to revive. Ethiopia has wrestled with ethnic violence and political polarisation that threaten to divert resources from development to security. The Dam, erected in an era of comparative calm, now stands as both a beacon and a barometer. Its promise will be fulfilled only if guns across the Basin fall silent.

In this sense, proponents call GERD a peace project, a test of whether mutual gain can trump zero-sum rivalries that have scarred the region for generations.

The symbolism radiates even farther, toward the Red Sea, whose littoral states have become host to competing military bases and contested shipping lanes. Advocates of an “African Lake Meles Zenawi” see in the Dam a template for turning strategic waterways from flashpoints into engines of shared prosperity. If Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt can map out equitable water management, the argument goes, perhaps Eritrea, Djibouti and Saudi Arabia can likewise negotiate shipping corridors and fisheries without escalating tensions.

The logic is aspirational, yet GERD itself, once a fantasy and now a reality, reminds observers that aspirations can, under disciplined leadership, harden into concrete results.

Naming the new lake after Meles would place Ethiopia alongside countries that honour transformative leaders through infrastructure.

Americans drive across the Hoover Dam, named for the president who oversaw its Depression-era construction. New Yorkers land at John F. Kennedy International Airport, an ode to a leader linked to a more confident America. Kenyans salute Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, South Africans fly through O.R. Tambo International, and residents of Gqeberha still refer to the surrounding metro as Nelson Mandela Bay. Such namings are not mere vanity. They anchor collective memory, turn geography into biography and offer future generations a narrative of how ambition reshaped their surroundings.

In Ethiopia, that narrative involved sacrifice at every level. Workers on fixed salaries bought low-interest bonds, sometimes skipping family purchases to contribute a month’s wages. Street vendors set up collection jars for spare change. Children sent pocket-money notes reading, “For our dam.” The project’s budget, publicly undisclosed in early years to thwart external pressure, eventually swelled to an estimated four billion dollars, a staggering sum for a low-income country.

For many participants, GERD remains a point of personal pride. A proposal to christen the water as Lake Meles Zenawi feels less like state propaganda than a fitting acknowledgement of the spark that lit their own sacrifices.

Egyptian policymakers may still bristle at the idea. Cairo’s initial objections framed Ethiopia’s initiative as an existential threat, invoking century-old colonial treaties that granted Egypt veto power over upstream projects, treaties Ethiopia never recognised. However, Egypt was also a founding member of the OAU and later endorsed NEPAD’s vision of integrated development. If those commitments are to be more than diplomatic slogans, then embracing the GERD as an African mega-project aligns with Egypt’s own professed ideals.

Cooperation could, over time, yield side agreements on power purchases and food-security corridors, softening tensions born of hydro-political anxiety.

None of this should obscure the risk that conflict poses. Sudan’s war continues to devastate communities that would otherwise profit from regulated irrigation. Ethiopia’s border disputes and internal strife drain funds that could be used to underwrite transmission lines and rural electrification. In this volatility, the GERD could be taken as a physical plea for stability, a reminder that prosperity requires predictability, and that the region’s water, like its future, is best managed collectively.

Ultimately, the GERD is more than a hydroelectric complex. It is a continental proposition about self-financed development, a statement that Africans can marshal local capital and engineering talent to solve local problems. It is also a testament to continuity in Ethiopian governance. Meles imagined the project, Hailemariam safeguarded it through transition, and Abiy delivered its first watts to the grid. Their combined effort illustrates an uncommon thread of strategic persistence.

As the reservoir rises behind its 510-foot wall, drawing a new blue shape on satellite maps, it also elevates expectations. Farmers, engineers and schoolchildren share a stake in its success. The name "Lake Meles Zenawi" should serve not merely to honour an individual but to encapsulate a broader lesson. Grit, vision and collective resolve can, even in a contested environment, sculpt a shared future.

In an era when global headlines often highlight Africa’s conflicts, the GERD offers a counter-narrative of an ambition fulfilled. Its concrete piers and humming turbines broadcast a simple message downstream and beyond. When a leadership aligns with the popular will, even a river as storied as the Nile can be disciplined to lift the fortunes of many.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 13,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1324]

Photo Gallery | 180514 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 170707 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 161777 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137289 Views | Aug 14,2021

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...