Radar | Mar 21,2020

Nov 5 , 2022.

Hardly were people prepared for the deals announced last week from Pretoria, South Africa. For many, it was a bolt from the blue moment.

Negotiators representing the federal government and those of the TPLF signed a "permanent cessation of hostilities" on November 2, 2022. It was a symbolic date, two days away from the second anniversary of the civil war broke in the Tigray Regional State.

Ethiopians may not be strangers to militarised conflicts. However, previous civil wars pale compared to what transpired in northern Ethiopia over the past two years. They are perhaps the bloodiest in Ethiopian history, with intensity, cruelty and gruesomeness unimaginable in the 21st Century. The military balance swung from one side to the other frequently, but neither party achieved a final victory to end the war decisively. The good-old tradition of "captured peace" remains elusive.

Instead, the recurring shifts in the battlefield continued to put the civilian population under siege and horror. Parties to the conflict have committed appalling mass atrocities, often filming their viciousness and posting them on social media platforms. Sane people worldwide dreaded these images and the state of a population under brutal siege. The ineptness to stop the carnage remained the source of frustration for many in and outside the country.

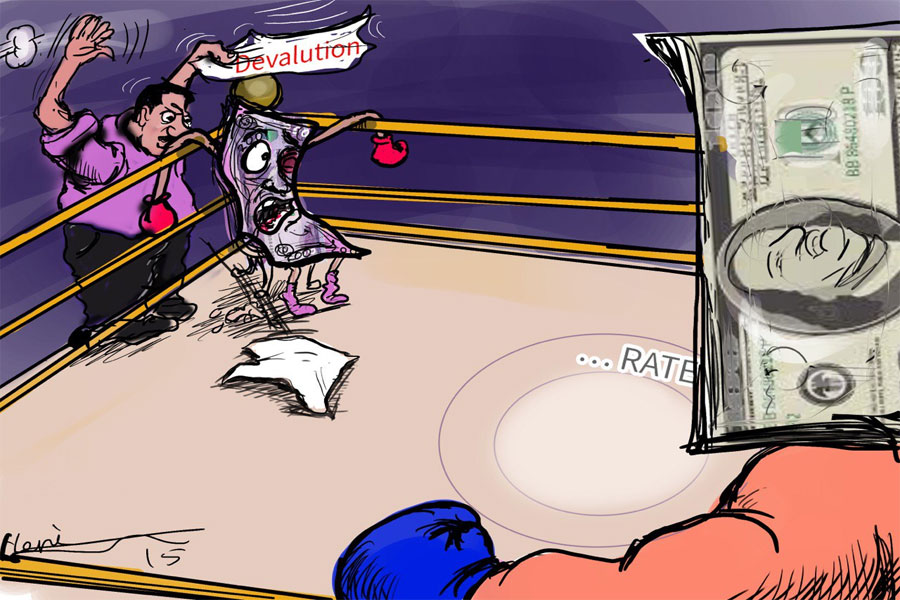

Once home to one of Africa's fastest-growing economies, Ethiopia is floundering as the war in its Tigray and neighbouring states has reignited; weary citizens far from the frontlines are pleading for a respite. The economy has faced the highest inflation in a decade, foreign exchange reserves have plunged and mounting debt amid reports of massive public spending on the war effort tanked it. The destruction of infrastructure and uncontrolled spending harms the economy, while citizens see their income eroding as poverty levels rise.

Poverty head counts in the Tigray Regional State jumped to 45pc this year compared to 27pc in 2016. This can be attributed directly to the war raging there. The outlook for other areas is no less grim. Addis Abeba and Dire Dawa also saw their poverty headcounts increase from 24pc and 23pc this year, respectively, compared to 17pc and 15pc six years ago.

The year-on-year inflation rate soared from 18pc before the war to 36pc this year. Food prices spiked 40.7pc to a 10-year high, threatening Ethiopians' living standards and food security, further exacerbating poverty and unemployment. The soaring inflation rate can be attributed to the government's increasing military spending, which caused a budget deficit while tax revenues dropped. The security situation affected agriculture and industries across the country and disrupted essential food supplies.

Few opportunities had emerged to end the war, nonetheless. But neither Ethiopians nor the international community seized them to bring peace. History will not be kind in its judgment of global leaders from this era over their utter failure to protect hundreds of thousands that perished in vain. Millions continue to languish in camps, weak from hunger and disease.

The efforts and pressure they put, however lukewarm, compelled leaders of the warring parties to sit for a formal and public meeting in Pretoria to reach an agreement that may pave the way for peace. But first, the guns needed to get silent. The hope against all hopes was to see them agree on a cessation of hostilities, eventually leading to a deal on a permanent ceasefire.

What came of the Pretoria Accord was more profound. It resembles a full-blown peace accord, such as Egypt and Isreal signed in the late 1970s after negotiating for 13 days in Camp David, the United States.

Says former US President Jimmy Carter, the umpire of accord: "Only through high ideals, through compromises of words and not principle, and through a willingness to look deep into the human heart and to understand the problems and hopes and dreams of one another can progress in a difficult situation like this ever be made."

Undoubtedly, the former African heads of state mediating the peace talk between Addis Abeba and Meqelle made progress, whose outcome was least expected.

The Pretoria Accord envisaged the disarmament and demobilisation of armed forces in Tigray - described as "TPLF combatants" in the agreement - and their eventual reintegration into the national defence force. A deal is made to see the federal government cooperate with humanitarian agencies to speed up aid to those in need. The resumption of public services, rebuilding infrastructure in all communities affected by conflict, and restoring constitutional order in the Tigray Regional State are vital points of agreement. No less crucial is the establishment of a framework for the settlement of political differences.

Addis Abeba has made significant political concessions while Meqelle gave in militarily. The negotiators made a courageous deal that made many of their respective supporters despair, leaving them anxious.

It is courageous because the negotiators displayed awareness of a stalemate on the battlefields and the prospect of a worse future on the economic front where political engagement is absent. Coming to terms with the fact that the civil war was caused by political disagreements that needed to be resolved only through political engagements takes intrepidity. Engaging with and building peace takes more courage and sober minds than advocating for war. The resistance comes from within. History from Camp David to Oslo shows that leaders who made powerful gestures in the service of peace have paid prices in their lives.

Not everyone is happy with the accord reached last week. Many in both camps feel despaired with the sentiment that their side has been humiliated out of this deal. Each camp has a vocal support base that believes its side has given too much, and compromises were made on principles and beyond words. The sense of betrayal by the respective negotiators is deep. The despair demands time to heal.

There is also a profound sense of anxiety over the prospect of implementing the accord.

Signing a peace deal on and of its own will not do much for the millions whose lives were wrecked and at stake. Chief negotiator Olusegun Obasanjo rightly said last week's deal is the beginning of a long and arduous road to durable peace. The world is rich with cases of promising accords going helter-skelter during implementation times. The anxiety that so much may go wrong when the "agreement on permanent cessation of hostilities" is enforced should be understandable.

The role of the United States as the bondsman of the agreement is evident. However, Washington wanted it to appear the process was driven by the African Union (AU), whose officials fancy themselves with their slogan, "African solution for Africa's problems." It deployed its political and diplomatic leverages to twist arms and pressured both parties to bend as low as they could. It can continue to use the same leverage to see both sides show fidelity to the agreement they signed, in partnership with its allies, including the European Union (EU).

Relapse to warfare should not be allowed. The peace dividend must reach those who face the raze of destruction. The peace agreement must develop adequate measures and means of enforcement to sustain humanitarian aid to the needy and uplift the country's already tanked economy. The dissatisfaction and misgivings due to an agreement many could view as unfair and unjust should find peaceful, legal and institutional outlets to address.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 05,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1175]

Radar | Mar 21,2020

Radar | Jun 05,2021

Radar | Mar 26,2022

Fortune News | Jul 29,2023

Fortune News | Jul 15,2023

My Opinion | Aug 10,2019

Radar | Jan 01,2022

Editorial | Dec 17,2022

Fortune News | Jul 08,2023

Commentaries | Feb 24,2024

Photo Gallery | 175177 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 165402 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155705 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136783 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In a sweeping reform that upends nearly a decade of uniform health insurance contribu...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A bill that could transform the nutritional state sits in a limbo, even as the countr...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A long-planned directive to curb carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles h...

Oct 18 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

Transaction advisors working with companies that hold over a quarter of a billion Bir...