Radar | May 24,2025

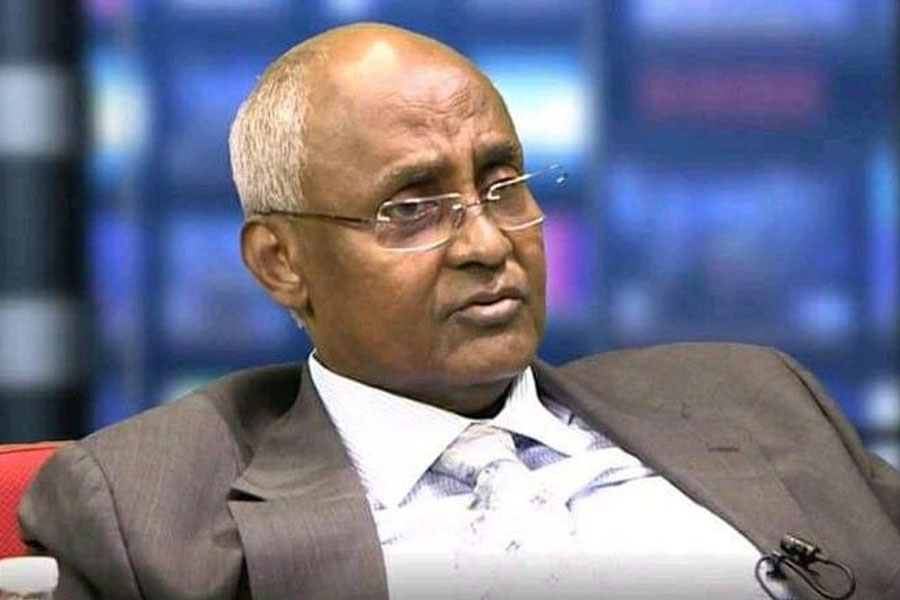

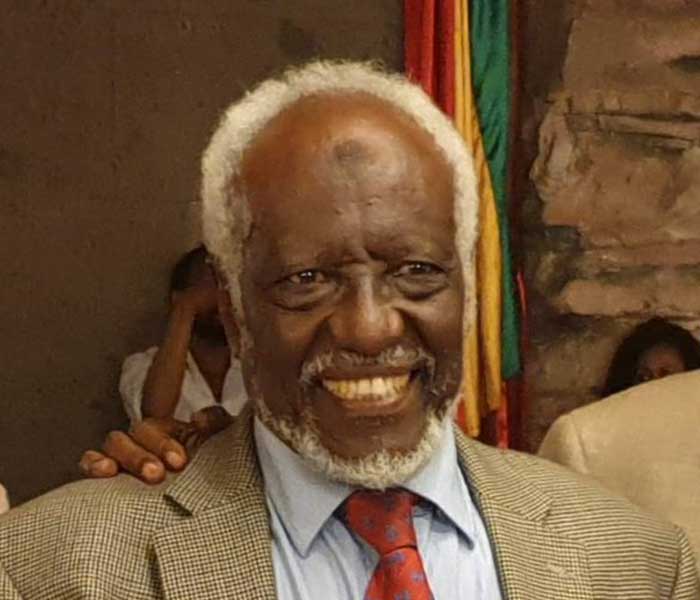

Mesfin Woldemariam (Prof.) took poetic license. An 18-year-old who had read one of his poems found this out by accident. A freshman pre-med student at Addis Abeba University in 1982, he was classmates with Zesemayat, one of Mesfin’s daughters. They used to walk together from the science faculty, where regular classes took place in Arat Kilo, to the Sidist Kilo compound where common courses were delivered.

On one of these days, nonchalantly, Zesemayat invites her friend to the office of a man who, even then, could be identified with just his title, “Professor.” His office in the University’s Sidist Kilo compound, where he was a geography professor, was full of books. There were just two chairs and a coffee table. Sitting behind his desk, he was hidden by a stash of papers. An ashtray was displayed prominently in front of him.

The friend was awestruck. But he would go on to be even more impressed when Zesemayat mentioned to her father that the friend had a mild criticism of sorts over one of the poems Mesfin had written. As she was mentioning this, Mesfin lit a cigarette. Then he put it on the ashtray and asked the young man before him to explain further.

“I had the floor, and I took my time explaining,” says the pre-med student, whose name was withheld by Fortune. “He wanted to know what I had gotten out of the book. His attention was undivided.”

Their discussion had to do with Mesfin’s conception of taking poetic license to meet some of the artistic and aesthetic requirements of a good poem. After the 18-year-old finished explaining his position, the Professor went to express his ideas. Status and titles did not matter. This was a meeting of minds, absorbing each party – a fresh-faced recent high school graduate on the one side, and a highly regarded public intellectual on the other.

By the time the two were finished, the cigarette had burned out on the ashtray. Mesfin, who smoked into his 70s, had not taken a single drag after lighting it. The Professor had forgotten about it. The young man never will.

“He was interested in ideas more than anything else,” says the friend.

That is true. He loved ideas. But his ideas were not loved by all. In fact, Mesfin’s passing on September 30, 2020, of complications from the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) stirred emotions that were no less symptomatic of Ethiopia’s politics of binary, where no grey areas exist.

To his closest friends, supporters and political allies, Mesfin was a resolute human rights defender that left the country’s politics better off than he found it. For his detractors, he was not much better than an enabler of subsequent oppressive systems – Emperor Haile Selassie’s feudal regimes and theDergue’smilitary dictatorship. He was a man that was loved with almost as much intensity as he was abhorred.

Inarguable, nonetheless, was the sheer diversity of the subjects that interested him.

He was a geography professor who was interested in poetry. He was an academic researcher with political contributions and human rights advocacy. Testifying to his diverse set of interests were the books he published through an active public role that survived three different regimes.

Among his famous books were “Rural Vulnerability to Famine in Ethiopia: 1958-77,” “Suffering Under God’s Environment,” and the “Horn of Africa: Conflict and Poverty.” “Engurgur” is a famous Amharic poetry book of his, and “Adafne: FirhatinaMekishef” was one of his most recent.

Many of the professor’s writings, including in newspaper articles, dealt in large part with politics. He did not have the aspirations nor the disposition to become a politician, however.

“He is too honest,” according to Girma Seifu, who worked with Mesfin in the Coalition for Unity & Democracy (CUD), aka Kinjit. “He was unlikely to go along with something just because the majority agreed, even if it was politically expedient.”

In fact, Mesfin was prone to calling things as he sees them, a major disadvantage a politician could have. It was a trait that extended to those he knew closely. He told it as he saw it.

Arguably, his most crucial contribution came in his human rights advocacy, gaining recognition for being one of the founders of the Ethiopian Human Rights Council. The institution was notable in its condemnation of government activities that it deemed violated the rights of individuals. It was even more well-regarded for its stubbornness against a government that would go on to put Mesfin in prison for his political activities. Indeed, its efforts caught the attention of international organisations such as Amnesty International.

It was the case, of course, that Mesfin’s belief in fighting for the rights of anyone “human,” was noted in its omission and commissions. Among his credits have been the boldness to speak out against the deportation of Eritreans as the drums of war were being beaten in Ethiopia against the new East African state in 1998.

Noteworthy among his supporters was also the nuanced view he held during the heady days of the Student Movement. One of the participants, Paulos Milkias (Prof.), now a professor at Concordia University in Montreal, remembers him “admonishing” Walelign Mekonnen for penning his controversial piece, "On the Question of Nationalities in Ethiopia" in 1969.

“He was with us all the way when we launched the radical student journal Struggle, which castigated the feudal regime,” says Paulos. “Mesfin remained a mentor not only to me but also to many of my radical colleagues.”

Players on the "federalist" side of Ethiopia's political aisle were a great deal less impressed by Mesfin. In his reproval of a republic federated along lingo-cultural lines, they saw a reactionary. In his defence of a unified Ethiopia, they saw a chauvinist.

Mesfin’s human rights activism started in earnest in the early 1990s after the ousting of the Dergue, when the Council was founded. He is alleged to have been silent throughout the 1970s and 80s and was in fact a member of an inquiry commission that was implicated in deciding the fates of the 60 former officials of Haile Selassie’s government that went on to be executed at the orders of the Dergue.

“The commission’s findings were never revealed nor were the suspects given the opportunity to defend themselves in fair trials,” states Amnesty International in its tribute to the Professor.

Tesfakiros Aresa, a politician based in Meqelle, sees a legacy tainted by Mesfin’s own worldview but, nonetheless, went on to exert undue influence over Ethiopian mainstream media through his advocacy. The Professor was noted for his claim that there was in fact no such thing as an ethnic group that could be referred to as “Amhara.”

“He wanted to rob ‘Amharic’ of an owner and thus obviate the narrative of historical lingo-cultural domination,” says Tesfakiros, who questions the Professor’s creed as a civic nationalist. “He attempted to advance the particular nation-building process begun by Emperor Menilik, but through an ‘Ethiopianist’ cloak.”

Ayantu Ayana, a PhD student at UCLA and activist, also sees advocacy of rights and an Ethiopian vision that was exclusive in all but name.

“His vision of Ethiopia had no room for the identities, cultures and histories of historically marginalised nations,” she says. “His ‘human rights’ work applied only to those who fit his exclusive definition of ‘human.’”

Mesfin was well aware that he had detractors. But he remained resolute in his conception of Ethiopia. He was a patriot, who wanted his days to end in the country. He even wrote that, despite being a devout Orthodox Christian, he would rather be cremated and his ashes scattered in the Awash River, a river that begins and ends within the borders of Ethiopia than die outside of the country. In the end, he was laid to rest at the Holy Trinity Church last Tuesday.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 11,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1067]

Radar | May 24,2025

Radar | Dec 08,2024

Fortune News | Jul 08,2019

Viewpoints | Sep 04,2021

Obituary | Aug 08,2020

Radar | Apr 29,2023

Obituary | Feb 29,2020

Obituary | Oct 03,2020

Obituary | Oct 17,2020

Fortune News | Oct 10,2019

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...