Fortune News | Apr 28,2025

Jun 1 , 2019

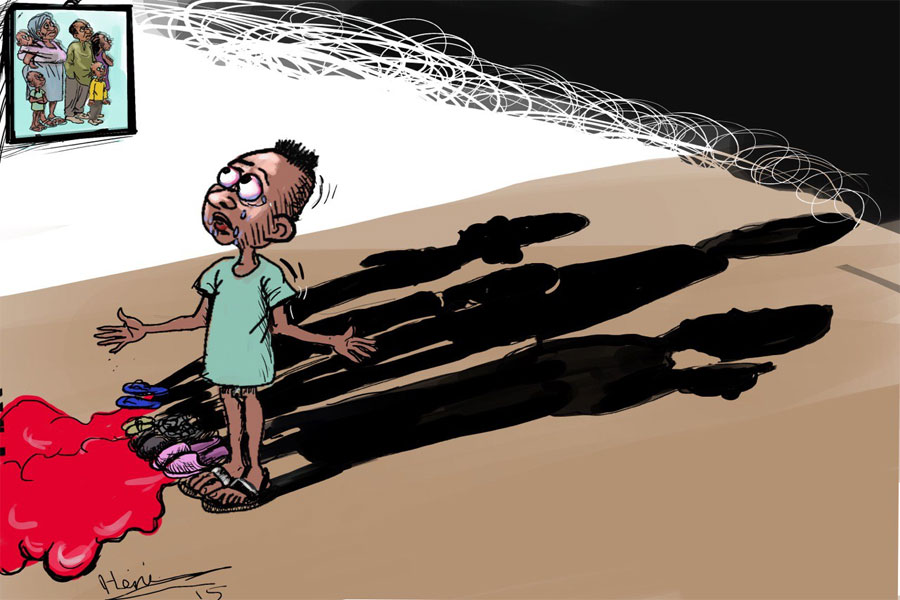

When justice is inaccessible to ordinary citizens, it breeds discontentment and anxieties that lead to social deterioration, writes Ambessaw Assegued (assegued@anfilo.com).

The judge sits behind his desk in a cluttered room and spreads open a file that is tethered by a worn and frayed file cover, gingerly beginning to examine the documents inside. Two litigants file in and stand in supplication in front of the desk, waiting with some degree of apprehension, for it is the third time that they have been summoned in front of the judge who is handling their petition.

“So, what is your case about?” says the judge sternly, as if to forestall any lengthy explanation, but his question sends the litigants into fumbled and confused invective that the judge soon loses patience.

“What does the case involve?” he demands, as the litigants fumble once more. They stand temporarily pinned, throwing hopeful glances at the judge with the inquisitive look that seems to say, "surely, you know what this case is about." They twitch and shuffle, lost in how to reply to the judge. They seem to plea for some recognition. They silently look on as if to ask, "You have had the file in your hands for the last four weeks, didn’t you?"

But it soon becomes apparent that the judge is utterly ignorant about the case and that he has not read a single document in the file in preparation for the hearing. He continues to toss and flip the pages in the dossier when one of the litigants, now fully recovered and coherent, elegantly summarizes the case to the impatient magistrate. When finished, he stands expectantly, waiting for a rejoinder or an affirmation that he has been understood.

“You should return back to the Execution Court and try to work out the problem with them,” utters the judge to the complete consternation of the petitioners, who look around the room bewildered, searching for some celestial intervention for their predicament.

But how would such intercession materialise in the cramped chambers of the Federal High Court at Tor Hailoch, where in a single crowded room three judges sit behind their desks and hold court, their clerks weaving between a slew of litigants filing in and out of the room constantly - all pleading their petitions in an atmosphere of pandemonium?

He is the third judge assigned to the case, he has kept the file with him for over a month without examining it and made the litigants return to the courtroom three or four times without a hearing the judge ignores the litigants’ explanation.

“Please wait outside for now,” comes the abrupt order from behind the desk, and a female clerk directs the two to the waiting area. Never mind that they have waited outside the same familiar corridor with all the other litigants, lawyers and witnesses for days.

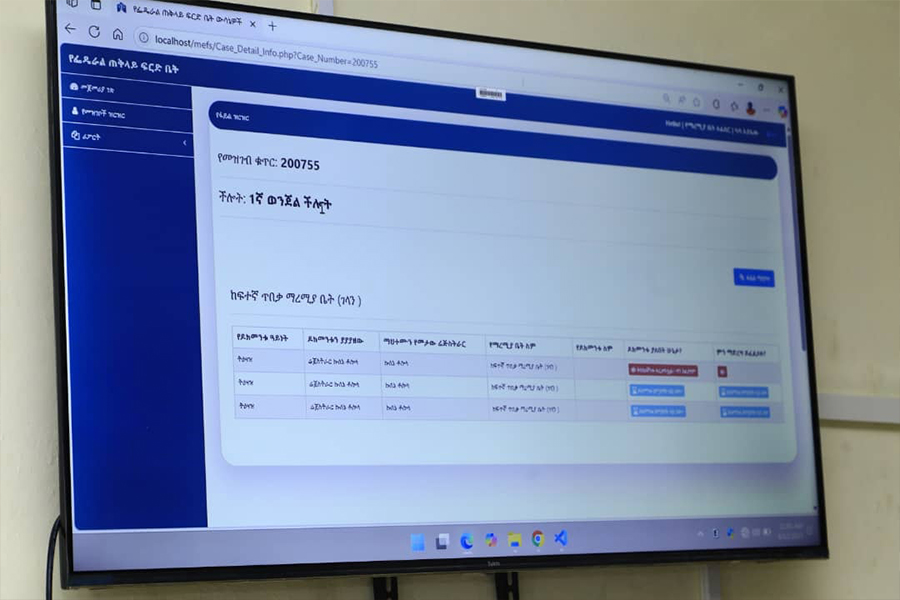

Once the appellants’ file disappears altogether from the court, and it takes several trips to the Ledeta courthouse and back to Tor Hailoch to find it. It finally shows up after a strategic investment of small capital is made, and it turns out that it never left the chamber after all.

It is a simple case of property division that should have taken no more than two or three rounds of court sessions to settle. But the case of the two litigants has been wallowing in the system for over four years, where it has bounced back at least twice to the High Court by the Execution Court in Sidist Kilo. The Federal Execution Court is also a warren of offices where six or seven desks are arrayed in a single room from where civil servant clerks roost mightily, yielding unfettered authority over the judgments passed by the federal courts.

In the absence of proper power delegation, unrecognizable procedures, inconsistent calendars and irregular schedules in the court system, the judicial clerks' rule sovereign.

At the Execution Court, a document needed a simple correction, but the clerk who penned it was out for a few weeks.

“You have to return when he comes back. He is on leave for three weeks,” comes the supreme voice of another clerk from an adjoining desk to the citizen who is distraught by the unexpected delay.

“Couldn’t one of you make the correction?” tries the citizen.

“He has the laptop with him, and none of us has the document to make the corrections,” answers the clerk. How a civil servant would take a laptop used for government work with him while he is on leave is an incomprehensible quandary that will never find a proper answer in this country.

A legitimate expectation from the judicial system is that a citizen will derive certain benefits including the protection of their rights and fairness. Another expectation is that the judicial system will not depart from its customs and procedures to the detriment of petitioners.

When the customs and procedures of the courts are constantly in flux, operate randomly and when the justice system deviates from its purported procedures, it breeds insecurities, resentments and anxieties among the common people. The fundamental failure of the state is that it has allowed these problems to fester for too long.

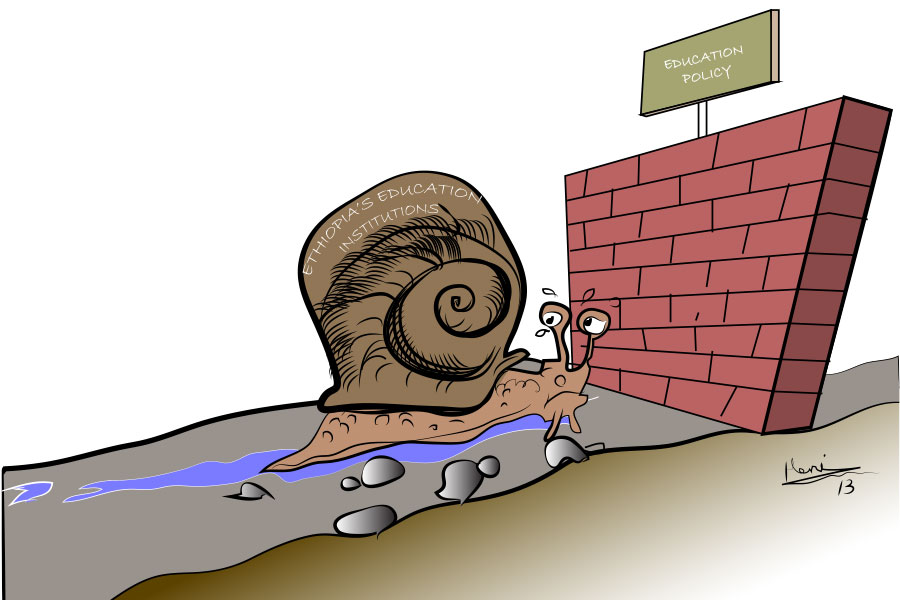

There are numerous other problems confronting Ethiopia, but top among them is a broken justice system where disorganised case management, absence of proper procedures and prolonged execution of final decisions by the courts fosters lingering discontent among the populace.

Judicial reforms, despite the common refrains of the current administration; the establishment of numerous reform committees; and despite the props of interminable television discussions, have not yet landed on the ground from the idealized universe of the intellectual realm.

PUBLISHED ON

Jun 01,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

996]

Fortune News | Apr 28,2025

Viewpoints | Aug 26,2023

Fortune News | Jul 19,2025

Fortune News | Jul 08,2023

Commentaries | Jan 16,2021

Editorial | Oct 03,2020

News Analysis | May 04,2025

Commentaries | Apr 26,2025

Life Matters | Jun 21,2025

Editorial | Dec 10,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...