Radar | Oct 05,2024

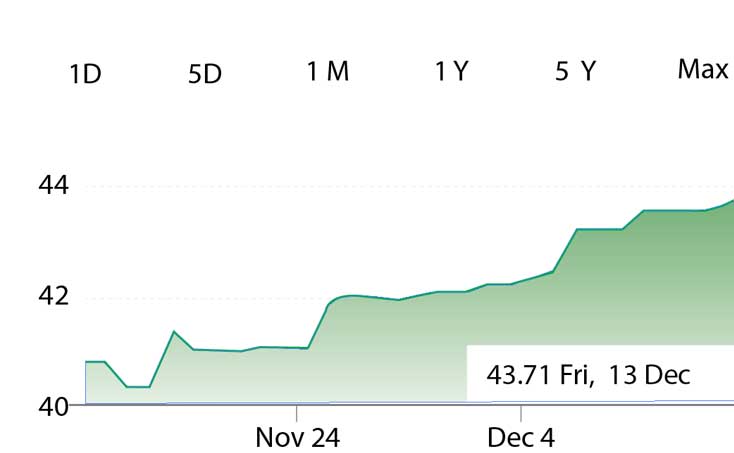

Exchange rate of the Birr against the IMF's Special Drawing Rights (SDR).

Exchange rate of the Birr against the IMF's Special Drawing Rights (SDR). The Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is due to meet this Wednesday, December 18, 2019, to decide on a 2.9-billion-dollar loan for Ethiopia, offered to finance its economic reform package.

Close to 700pc larger than Ethiopia's quota of 300.7 million dollars in the IMF's special drawing rights (SDR), the loan will be the largest ever since Ethiopia joined the IMF as a founding member. Ethiopia has had five programmes with the Fund since its formation in December 1945.

Such an arguably generous programme was followed last week with yet more financial support, three billion dollars in loans, from the Development Assistance Group (DAG), a consortium of 30 bilateral nations and multilateral agencies supporting Ethiopia. This will allow Ethiopia to secure a combined six billion dollars for the realisation of its Homegrown Economic Reform package.

Jointly chaired by the World Bank and Sweden, DAG confirmed the financing package on Friday, December 13, 2019. However, the World Bank's support is not part of this financing, for its officials are in talks with the government for financial support packages separately, according to senior administration officials familiar with the process. Discussions are in progress between Ethiopian authorities and the Bank over additional provisions of budget support of up to three billion dollars, yet to be approved by the Board of Directors.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's (PhD) administration has launched a three-year reform package, hoping to correct imbalances in the economy, defined with having a severe foreign exchange crunch, high inflation rate, mounting debt stress and high unemployment. The national economy suffers from the twin structural ailments of low productivity and uncompetitiveness.

Designed by a team of experts from the central bank, the Ministry of Finance and members of the macroeconomic team at the Prime Minister's Office, the reform package is designed to address structural, institutional and sectoral bottlenecks to growth. It aims at ensuring the creation of millions of jobs, giving access to credit and capitalising on the unlocking power of technological advancement.

Prime Minister Abiy describes the reform as a "pro-job, pro-growth, and pro-inclusivity pathway to prosperity."

In September this year, Governor Yinager Dessie (PhD) of the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) and Eyob Tekalegn (PhD), state minister for Finance, made a joint appeal to the international community to foot part of the bill for the reform package, which is estimated to cost 10 billion dollars.

"The development agencies have started to respond to our calls for help," State Minister Eyob told Fortune.

The loan from the IMF, through its dual extended credit and fund facilities, will be provided to address the foreign exchange shortage; strengthen the management of state-owned enterprises and contain debt vulnerabilities, according to a brief statement from the IMF issued last week. It is also meant to enhance domestic revenue mobilisation; reform the financial sector; and strengthen the government's supervisory role and financial safety nets.

The series of fundings show that these agencies have developed trust and confidence in the reform plan, according to Eyob Tesfaye (PhD), a well-known macroeconomist.

"This can bring a paradigm shift in the economy," said Eyob. "It's an extremely good opportunity for Ethiopia."

Not all who are keen observers of the macroeconomic evolution are on the same page and as optimistic. To the contrary, the desire by the IMF to inject a massive amount of loans, a little more than the country's revenues from exports, exposes the extent to which the economy is in a deep hole.

Such is a view strongly voiced by Getachew T. Alemu, an economist and a consultant. He cautions that the latest window of help from the IMF signals the severe balance of payments crisis in the economy, citing the IMF's noninvolvement in development financing.

"The help shows the country needed an external interjection to solve its balance of payments crisis," he told Fortune.

The overall balance of payments during the third quarter of the last fiscal year stood at 124.1 million dollars in surplus, four times lower than a year ago. The increase in merchandise trade and net services deficit, coupled with the decline in official transfers and capital account balance, are attributed to this development.

Getachew believes the support will build trust in other international agencies toward Ethiopia.

"Once they see the IMF puts money into Ethiopia," said Getachew, "others will be confident investing in the economy."

To fully secure the finance for the reform package, the administration is also using negotiations for loan rescheduling as an alternative mechanism supporting the country's precarious balance of payments.

"We're negotiating with Middle East countries, including Saudi Arabia, for loan restructuring and rescheduling," Eyob, the state minister, told Fortune.

Since the administration announced the reform agenda a few months ago, it has been rolling out a couple of policy changes. The central bank removed the 27pc mandatory bond, which private banks have been buying whenever they approve loans and advances. The central bank also relaxed the primary market by allowing the yield of treasury bills to be determined in the open market.

The administration has also eased the investment climate, amending the investment law to allow for the private sector and foreign companies to enter areas that were previously reserved for the state. The proclamation that will gear up the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, including Ethio telecom, is also now at the final stage, tabled to lawmakers for legislation.

The reformers in Abiy's administration are lobbying the international community for resources, pitching these changes among the upcoming ones. They call it "a subscribed approach" not "a prescribed approach". It is their way of rebuking their determined critics that they are sold to the wishes of the global neoliberal agenda.

One of these critics is Alemayehu Geda (prof.), a macroeconomist lecturing at Addis Abeba University, who believes the Homegrown Economic Reform Programme is "basically an IMF/WB policy."

"The IMF and our government don't seem to care about the inflationary consequence of their devaluation policy, which hurts the poor most," Alemayehu tweeted recently, in response to news of the IMF's plan to provide loans for Ethiopia.

There is a loud voice of caution emerging that warns these forms of financial packages will not come without strings attached at the expense of the poor and the erosion of capital formation by the domestic private sector. It is a fear invoked by the IMF statement last week that the loan aspires to help Ethiopia make the "transition to a more flexible exchange rate regime."

Unvarnished, it means the administration may relent under years of pressure by the IMF for Ethiopia to begin floating its currency, the Birr, to get exchanged by market forces. This may lead to the exchange rate of the Birr crawling toward 40 Br to a dollar, according to Getachew.

"The floating of the currency in such an import-dependent nation implies nothing but inflation," he told Fortune.

Inflation has been on a constant rise since 2016, doubling the single-digit growth - eight percent - in gross domestic product (GDP). The IMF projects that the disparity between the GDP and inflation will continue up until 2025, although the gap will narrow significantly from 2023 onward.

Nonetheless, the speculated plan to introduce a floated exchange rate regime is vehemently denied by senior officials of the administration. State Minister Eyob told Fortune, "There is no floating plan whatsoever."

However, it is clear for both critics and policymakers that the fixed exchange regime will not remain sustainable for long.

"Gradual exchange rate liberalisation should be employed, moving toward a flexible exchange rate," said Eyob, the macroeconomist.

Since mid-November, the Birr has been depreciating by approximately 0.3pc every business day. The question thus remains, what sort of change will the administration introduce to create a forex market away from the current quota system characterised by a structural shortage.

"The government will decisively deal with the forex imbalances through a comprehensive set of measures," Eyob told Fortune.

Mobilising forex, easing controls on forex sales to the private sector, allowing the exchange rate to become more flexible and market-determined, and implementing prudent fiscal and monetary policies are the measures planned by the government, according to Eyob.

"The objective is to correct the real exchange rate overvaluation, steadily moving toward the alignment of the real exchange rate with economic fundamentals, and improve the competitiveness of our exports in the global markets," Eyob told Fortune.

The funnelling of billions of dollars from bilateral and multilateral sources is believed to offer policymakers the buffer to guard the sudden and speculative flight of forex, depleting the reserve.

But less than a surgical approach to address the structural limitations in the economy, what the reform aspires to accomplish will have little to solve, according to macroeconomic pundits. The reform document may sound good in its diagnostic approach, but it does not have clear expected goals and targets, according to Getachew.

"This triggers a question; 'money for what?'" he said.

Getachew also argues that Abiy's administration has been trying to correct the imbalance with a facilitative aspect of the economy, not the structural constraints.

"The macro stance of the nation has not changed," he said. "Nothing has come in the form of policy that improves exports, enhances import substitution, reduces logistics costs, stabilises the agricultural value chain and reprioritises public investments."

Over the past few years, the export revenue of the country has stagnated to figures below three billion dollars, while the import bill stood five to six-fold higher than the export value, implying a considerable trade deficit.

For Eyob, the macroeconomist, policymakers start with adjusting some of the fiscal and monetary policies that will enable them to correct these macroeconomic imbalances.

"They have to go back to the drawing board and redefine their monetary policy stance," said Eyob, the macroeconomist.

Arresting and containing inflation, introducing an indirect monetary policy stance, introducing a government borrowing limit and liberalising interest rates, are some of the monetary policy measures Eyob recommends. Moving toward a balanced budget, ceasing capital investments without feasibility studies, restructuring and recapitalising government banks, applying fundamental reforms for the commercial and development banks, as well as introducing a mortgage bank, as fiscal corrective measures are what he would like to see policymakers focus on.

In this process, the government should expect a maximum GDP growth of seven to eight percent, according to Eyob. He is optimistic about the future, advising that sequencing, timing and speed are crucial to the reform.

"There has to be strong supervision from the Prime Minister himself," said Eyob. "There should be no room for failure."

PUBLISHED ON

[ VOL

, NO

]

Radar | Oct 05,2024

Radar | Apr 08,2024

Commentaries | Jul 13,2019

Fineline | Jun 14,2020

Fortune News | Apr 12,2020

Radar | May 03,2025

Fortune News | May 18,2019

Radar | Aug 12,2023

My Opinion | Mar 13,2021

Fortune News | Jan 07,2024

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...