Editorial | Oct 30,2022

Nov 2 , 2019

A Rwandan friend who was visiting Addis Abeba this week sat across from me and said, “When I read about Ethiopia today, I think of what happened to my country.”

Many people have made this comparison in the past two years. Life in Ethiopia has become unpredictable. While it may be easy to blame one or the other group, our own responsibilities for the stability of the country should not be overlooked as well.

Ethiopia is said to be among the most religious countries in the world. Beyond the statistics, at a very individual level, people tend to believe in a higher punishing and rewarding being. People believe in good and evil and that the afterlife will be determined by our time on this earth. With even all this, we are living at a time when too many people are casually talking about the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, fearing that devastation could take place once more. We hear and see the opposite of what is taught in religious institutions.

To live through a type of trauma like Rwandans have gone through cannot be the kind of future waiting for this country. We should all be outraged, yet the outrage is misplaced. My Rwandan friend tells me, “Do you know how devastating it is to have to rent parents for your wedding, because you no longer have any family left?”

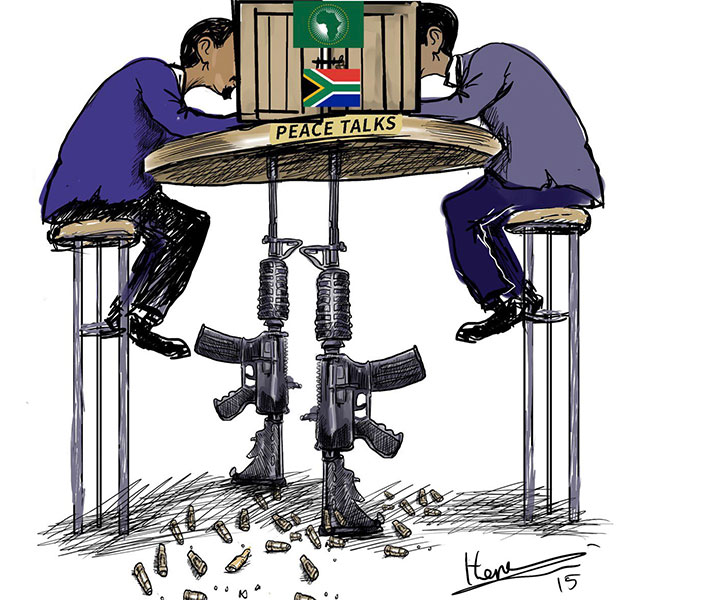

Peace is individually attained. It is the individual act of peace that can keep our nation safe. While we may all adhere to various beliefs, they must not be rooted in the oppression of another. Physical territory cannot be what we fight over, while we do not have the authority of our own minds. We have let those with ulterior motives take over the common sense of many.

Someone is expecting to win from all of this, but what could winning look like for us?

When we stop making our own minds up and choose loyalty to people instead of ideology, we become the playground for those who have individualist interests instead of a national agenda.

Our individual peace will guarantee the same to our nation. To be asked to defend an identity we have not chosen at the expense of others is manipulation. It is being played like a krar, bending to the will of others. Things like ethnicity, gender and country of origin are not changed by request. But choosing to love instead of hate, kindness in place of hatred, level headedness in place of blind passion are positive traits we can decide to embody.

A diaspora Ethiopian couple with a voice of certainty exclaim, “We can't live here. It’s so unsafe!” Where else would the rest of Ethiopia go? Where is safe for us, if not home?

It is upsetting to hear those with the option to live elsewhere share a casual and passive opinion about the nation.

This generation was meant to inherit a better Ethiopia. It used to be exciting knowing that our generation would be working toward solving problems that would catapult the nation forward. Today, we have taken strides backwards and begun creating problems that make it look like we are intent on destroying it.

Recently, while a political hopeful mentioned that conflict comes when we are trying to decipher what the past has meant to a nation, I believe this is also a conflict of a future. It is the inability to understand that history is badly documented. While in the past decisions may have been made to profit one or the other, the future is ours to construct. Decisions have to be made today toward a future that can benefit us all. If we believe that the past has been mishandled, individual efforts count to create a better future. Constructive thinking is the brick that makes the pillar, which holds up a strong nation.

Instead, we are choosing to self-segregate. Households are tuning in to news targeted specifically to their ethnic group. Savings are only entrusted to banks that have particular ethnic affiliations.

In the past, information was hard to find, and people had a sense of the unknown toward different ethnic groups. Today, instead of leading by example, we lead with fear. Those living in ethnically blended communities should do more to be inclusive. Watching women dressed in Oromo cultural clothes dance to music from Sidama or Tigray is a sign of coexistence. It is the sign that a celebration is only complete when these sounds are heard in one space.

It is the same feeling I have when I hear bells and prayers from the Christian church soon followed by a call to prayer from the mosque. This is the sound of home for me, this coexistence.

PUBLISHED ON

Nov 02,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1018]

Editorial | Oct 30,2022

Radar |

Sunday with Eden | Sep 06,2020

Radar | Mar 09,2019

Viewpoints | Apr 22,2022

Editorial | Jul 17,2022

Radar | Apr 27,2025

Fortune News | Jan 07,2022

Viewpoints | Dec 11,2021

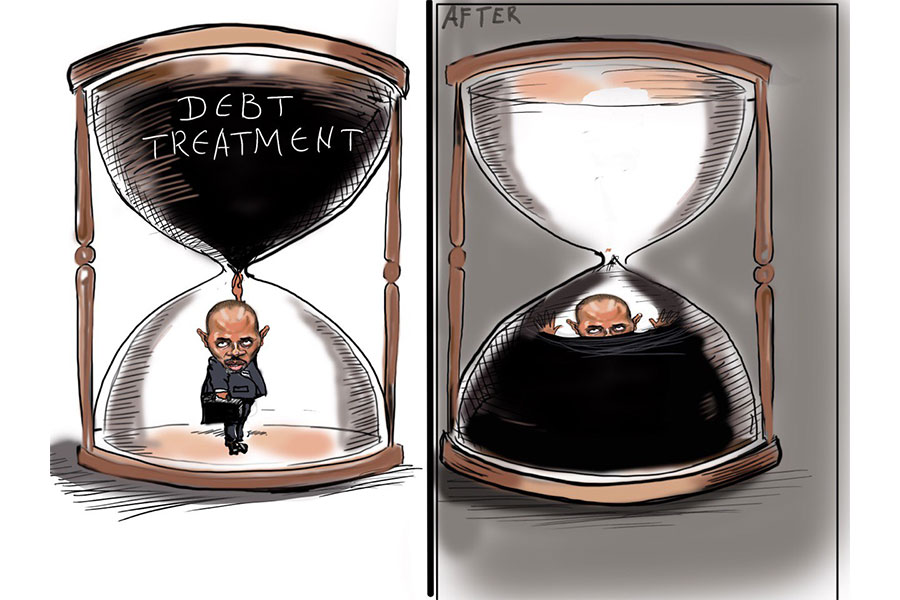

Fortune News | Oct 12,2019

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

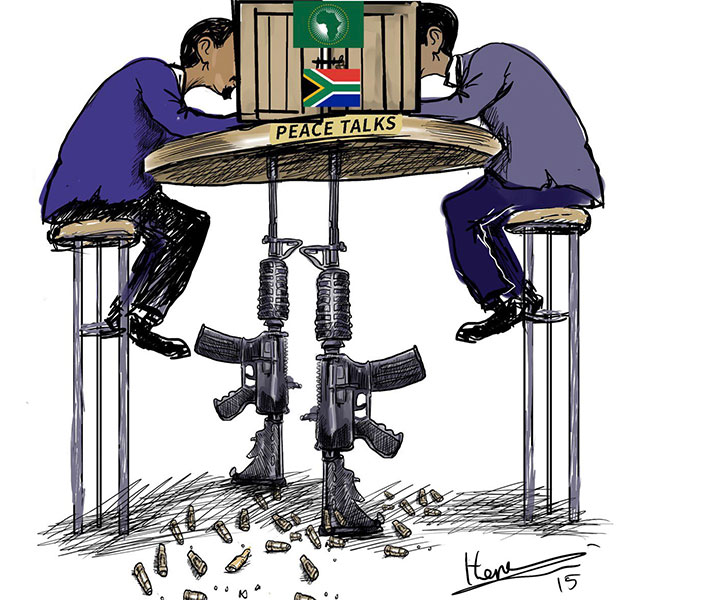

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...