Fortune News | Dec 25,2021

May 14 , 2022

By Christian Tesfaye

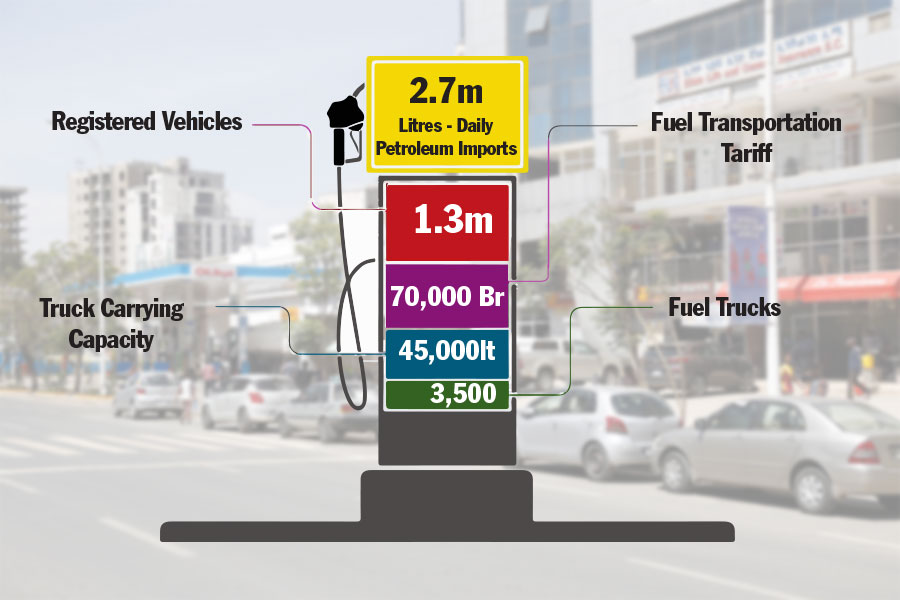

Last Saturday, the Ministry of Trade & Regional Integration dropped the bomb. Lines of cars have been queuing at fuel stations, hoping to hoard some black gold. It is no longer necessary now. Months of speculation about price hikes at the gas pump have been proven true. Retail prices for a litre of benzene have been raised by about 16pc.

The hard part is knowing that the recent price increase is not the last. The government has not been shy about its plan to completely phase out fuel subsidies, especially for non-public transporters. Once that happens, a litre of benzene could be double its current price.

How painful can it get?

First, a bit of history. For most of this country’s modern past, the global price of fuel had never mattered. There were barely any roads, cars or even cities except for Addis Abeba. Consumption was also low, including of fuel derivatives such as plastic. With a negligible urban population, low consumption and a subsistence economy, no one bothered with fuel prices.

It is not just domestic circumstances. Even the global fuel market was not nearly as volatile. The highest crude oil prices got between 1948 and 1973 was 31 dollars, while the lowest was 23 dollars. For perspective, between 1997 and 2022, in the same timespan, prices went as low as 19 dollars and as high as 184 dollars. This is after excluding the time during the COVID-19 pandemic when oil prices went into the negative. These are wild times.

Things changed in the mid-1970s when global prices suddenly soared in a manner never before experienced in the post-World War II era. In Addis Abeba, a class of people – taxi drivers – felt the pain and expressed their discontent through protest. Combined with the student movement of the day, it helped usher in a new era.

The way fuel prices poured fire over burning political calls for change has since been seared deep into the psyches of rulers and leaders that came after Emperor Haile Selassie I. However tough the going would get, the government would provide energy subsidies. This was never sustainable, and neither was it the right move. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's (PhD) administration's effort to end this irrational and politically-influenced economic policy should be supported.

Let us start with why it is unsustainable. Even at around 37 Br for a litre of diesel, Ethiopia still has one of the lowest fuel retail costs in the world. Look at some other countries at a similar level of development. In Kenya, a litre is around 62 Br; in Rwanda, it is around 66 Br; and in Uganda, it is 74 Br.

Most other countries like Ethiopia, which are net fuel importers, understand that it is not sustainable to continue to subsidise fuel, especially since, as the economy grows (and energy consumption grows), the government would need to pour an ever more significant chunk of the nation’s resources into artificially holding down gas pump prices. It is like a desert economy where ice cubes can be found at absurdly low prices; it does not happen unless the government is blowing a hole in its budget.

It gets crazier. For too long, energy subsidies have been sold to the public as pro-poor policies. Are they? Who uses fuel the most? A person using a minibus taxi, bus or train or someone else with a personal vehicle? Using some amateur statistis, private car owners have a per capita consumption that is about 12-fold that of a minibus taxi user (and much higher compared to bus or train users).

It gets worse. Given that prices are much higher in neighbouring countries such as Kenya, a fuel subsidy aids and abets a thriving contraband industry. Perhaps the most absurd episode with the short-sighted policy of energy subsidies came in during the 2007/2008 global financial crisis, when global oil prices reached 180 dollars. This so accentuated the cheapness of Ethiopia’s oil retailers that Saudi carriers would schedule stopovers in Addis Abeba to refuel. Basically, the Ethiopian government was subsidising carriers of the most oil-rich nation in the world.

This is not where the criminal nature of fuel subsidies in a country without oil resources ends. Some may ask, “but don’t lower prices at the gas pump alleviate the cost of living for the average urbanite? After all, this is felt in the wallets of the middle class whenever diesel prices go up.”

Not really. Whenever global fuel prices rise, the subsidies only provide artificial protection, not a real one. Consider this. Since the federal government always runs a budget deficit (almost all governments do), whenever the prices of fuel imports rise, the additional budget comes either from printing money or taking out loans. The latter exacerbates the sovereign debt burden (and, as the economy grows, to unsustainable levels) while the former fuels inflation. The middle class only feels like they are getting supported but are harmed indirectly.

It is long overdue that fuel subsidies are retired, and the budget is used to support food prices. Artificially low gas pump prices seem like a good thing on the surface, but it is only a wolf in sheep's clothing. It will be painful in the short term but worth it in the medium and long one.

PUBLISHED ON

May 14,2022 [ VOL

23 , NO

1150]

Fortune News | Dec 25,2021

Fortune News | Jun 25,2022

Radar | May 25,2024

Fortune News | Feb 12,2022

Viewpoints | Jun 25,2022

Fortune News | Jan 01,2022

Fortune News | Jun 08,2024

Radar | May 06,2023

Radar | Sep 07,2025

Fortune News | Oct 27,2024

Photo Gallery | 178874 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169073 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 159930 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137122 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | Oct 25,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...