In the verdant farming region of the Northern Shewa Zone of the Amhara Regional State, a crisis is silently unfolding. Amid the lush fields of onion, wheat, and teff, the subsistence farmers are finding themselves at the mercy of a crippling fertiliser shortage. The issue, causing havoc on the local farming communities, has been compounded by skyrocketing prices in the parallel market.

This acute scarcity, and the deep concern it engenders, is personified in the life of Solomon Teka.

Aged 48, Solomon is symbolic of the struggle faced by the region’s farmers. He tills three hectares of land, a medley of onion, wheat, and teff, to provide for his family of five. While a portion of his produce nourishes his family, the bulk of it is sold, forming their sole income source. The fertile earth under his care typically yields about 15qtl of teff and 40qtl of wheat yearly.

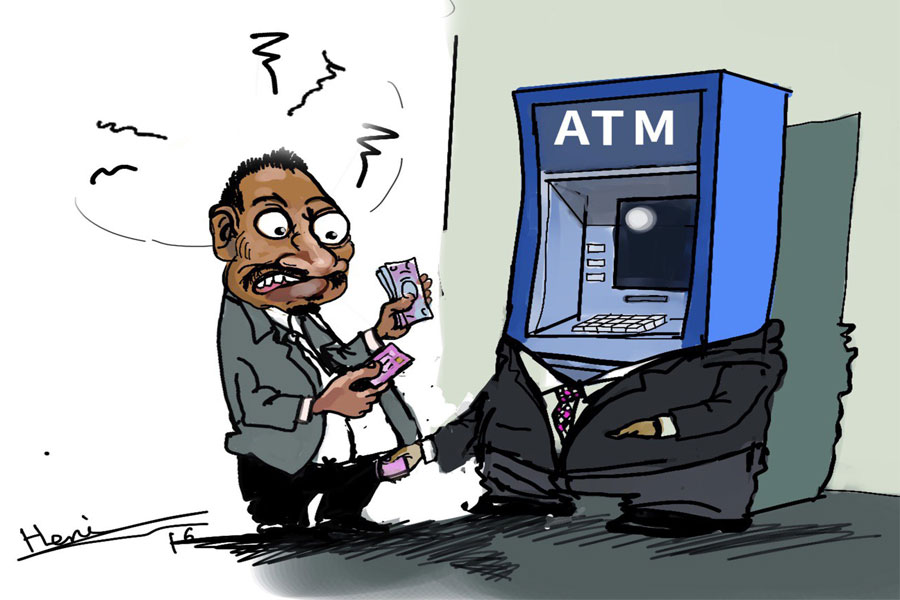

However, the key to such productivity lies in the 15qtl of NPS and Urea fertiliser that Solomon requires annually. Yet, the cooperative union he relies on could only afford him a quintal at the cost of 3,500 Br.

His quandary deepens as the parallel market whispers tales of three-fold price surges, pushing the fertiliser costs to an unimaginable 15,000 Br for a quintal.

“I would have bought it,” Solomon told Fortune. “It’s not like I have much of a choice.”

A palpable sense of dread pervades the region’s farming community, primarily engaged in the cultivation of teff, wheat and other grains across the sprawling 8.5 million hectares of farmland, yielding an aggregate of 29.8 million quintals of agricultural produce, according to recent data from the Central Statistics Services.

Official data from the region’s Agriculture Bureau paints a grim picture, revealing that only three million quintals were delivered to unions out of the 5.2 million quintals of fertiliser procured for the region.

Under the shadow of grey skies, a contingent of 20 farmers from the northern Shewa Zone, including Solomon, embarked on a 72Km journey to Addis Abeba last week, seeking an audience with officials at the Ministry of Agriculture.

This large group of petitioners hailed from the 23 weredas in Shewa Zone-a swathe of the country that accounts for a significant half million hectares of fertile Ethiopian land.

As the farmers arrived at the Ministry’s compound in the Gurd Shola neighbourhood, the signs of their rural existence were all too apparent: muddy clothing and worn boots, direct reminders of their lives on the farmland. They were not alone. Three suited men, representatives from the Zone’s Agriculture Bureau, offered a stark contrast and a symbol of the bureaucratic machine the farmers were set to face.

The Zone representatives emerged after what was undoubtedly a tense meeting within the Ministry’s stately buildings. A crowd of worried farmers, eager for updates and reassurances, quickly surrounded them.

Yet, instead of definitive answers, Bureau Head, Werqalemahu Kostre, offered only a request for patience. He shared with them that the much-needed fertiliser, the lifeblood of these farmers’ livelihoods, was still on its way.

Werqalemahu explained the challenge: only half of the staggering 761,818qtl of fertiliser demanded for the current production year had been distributed. The seasonal demand had increased, as a consequence of the region’s crop choices.

Compounding the issue were the logistical hurdles, with poor infrastructure and transport options exacerbating the supply difficulties due to growing insecurities.

Werqalemahu disclosed that while five individuals in the parallel market were apprehended, the challenge of delayed fertiliser delivery remains.

“It’s an issue requiring concerted efforts from numerous stakeholders,” Werqalemahu told Fortune.

Solomon and his farmer folks were left waiting in uncertainty and hope as their lives and livelihoods hang in the balance.

Further north, the brewing discontent found an outlet in demonstrations on the streets of Bahir Dar , the seat of the Amhara Regional State’s administration. Their aim was simple – to make regional and federal officials understand their plight.

The consequences of the fertiliser shortage have started to echo in the country’s food security situation. Over 56 million quintals of teff, a staple food in Ethiopia, were harvested from 2.9 million hectares of land. The Amhara and Oromia regional states contributed to over half of this production.

However, the dearth of fertilisers now threatens the next year’s crop yield, casting a shadow over the fate of farmers preparing the 8.4 million hectares of arable land in Oromia Regional State for the rainy season.

Faced with uncertainty, some farmers, like Belete Kassie from Adea Wereda, are contemplating a pivot in their crop choices. Unable to buy even a single quintal of fertiliser for his eight hectares of land, Belete is considering planting chickpeas, a crop less reliant on seasonal conditions.

He would be one of the 200,000 farmers in the region farming chickpea, who harvested 1.3 million quintals in 2021. Farmers in Amhara and Oromia regional states account for most of the 2.3 million quintals of chickpea farmers across the country harvested two years ago.

Officials like Takele Kurunde, head of Agricultural Input Supply at Oromia Agriculture Bureau, have forewarned this crisis. He disclosed that only 5.9 million quintals of fertiliser reached the unions' gate, despite a demand for 9.2 million quintals.

Takele had urged farmers to engage in compost-making, and claims 97 million cubic metres of natural fertiliser were prepared to help bridge the gap.

But for Yibeqal Getahun, a plant science researcher at Haramaya University, such an alternative cannot entirely replace fertilisers. He cautioned that production volumes could plummet by up to 40pc without the timely use of fertilisers, given that crops like teff have specific nutrient needs not met by the country’s soil.

Yibeqal emphasised the need for additional fertiliser, especially when using improved seeds.

Supply that meets farmers` demand is unlikely to arrive.

Executives at the state-owned Ethiopian Agricultural Business Corporation (EABC), the only fertiliser importer in the country managed by Kifle Weldemariam, procured 15 million quintals of fertiliser this year, for one billion dollars. This procurement data contradicts the Ministry of Agriculture’s report, which puts the figure at 12.8 million quintals.

Whatever the amount, the volume bought has not arrived in time for the main rainy season. Solomon Gebre, deputy CEO of the Corporation, blamed a delay in the letter of credit (LC) for the shipment delay.

“We’d signed with the suppliers immediately,” said Solomon of EABC.

The state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), the only bank authorised to open an LC for fertiliser imports, has been caught up in the bottleneck of a forex crunch, leading to the slashing of the initial plan to open 24 LCs in half until May.

Adding to the complications, the Ethiopian Shipping & Logistics Service, responsible for the delivery of fertilisers, has had to adjust its schedule due to the delay in opening the LCs in April and May.

Siraj Abdullah, the deputy CEO, disclosed that they had initially planned to complete transportation by the end of May. It was not meant to happen.

Against this backdrop, there is a glimmer of hope for change. Officials are contemplating allowing the private sector to import fertiliser, a move experts in the sector believe could address the pressing challenges.

Experts from the ministries of Agriculture and Finance, the Ethiopian Agricultural Corporation, and the Ethiopian Shipping & Logistics Service are exploring the idea of bringing the private sector onboard to import fertiliser.

According to Melese Bedane, the input director at the Ministry of Agriculture, the study does not necessarily suggest a complete privatisation of the sector, but it does open the doors to “alternative options” in the upcoming year.

While this may not solve the immediate crisis, it presents an alternative to the state’s monopoly over the fertiliser market. This move could benefit farmers like Solomon and Takele, offering them a lifeline in uncertain times.

While this measure may arrive too late for the current season, the decision to open the sector to private importers might ensure that such crises do not mar future seasons.

“It’s better late than never,” said Alemayehu Geda (PhD), an economist at Addis Abeba University, commending the government’s attempt to address the fertiliser scarcity.

However, he cautioned that any solution must consider balancing the country’s earnings and expenses.

The direness of the situation can also be felt acutely in the realm of Ethiopia’s foreign trade. The federal government spent 134pc more on fertiliser imports than the previous year, amounting to 226.3 million dollars. This figure starkly contrasts the fertiliser supply, revealing an uncomfortable truth about Ethiopia’s agricultural predicament.

PUBLISHED ON

[ VOL

, NO

]

Radar | Jan 12,2019

Editorial | Oct 28,2023

Radar | Aug 17,2019

Agenda | Jan 15,2022

Fortune News | Jan 05,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...

Jun 14 , 2025

Yet again, the Horn of Africa is bracing for trouble. A region already frayed by wars...

Jun 7 , 2025

Few promises shine brighter in Addis Abeba than the pledge of a roof for every family...