Fortune News | Mar 09,2019

Djibouti remains cautiously optimistic in its relations with Ethiopia, its largest neighbour, offering an anchor for economic recovery and growth in the Horn of Africa. Its leaders aspire for integration built on modernised logistics corridors, an ambition for renewable energy, and the long-awaited promise of industrial diversification.

Samir S. Mouti, an investment advisor to President Ismael O. Guelleh, spoke at a high-level economic forum in Paris last week. Mouti raised the intricate interdependence between Djibouti and its much larger neighbour, stating the potential of this relationship to shape the region’s economic destiny. Mouti described Djibouti as Ethiopia’s gateway to the world, a linchpin for nearly 90pc of its landlocked neighbour’s trade.

Despite regional crises, including Ethiopia’s devastating civil war, Mouti described his country's relationship with Ethiopia as “an opportunity and a necessity.”

The two countries are bound by infrastructure, including the Chinese-financed Addis Abeba–Djibouti Railway. These connections not only facilitate commerce but also symbolise an intertwined fate for the two countries.

However, Mouti acknowledged the uneven playing field in this relationship. While Djibouti enjoys the benefits of a stable currency and liberal economic policies, Ethiopia struggles with a weakening Birr and stringent foreign exchange controls, a policy revised this year after 50 years of hegemony.

According to Mouti, Djibouti’s aspirations extend beyond simply serving as Ethiopia’s lifeline.

He was one of the panellists from Africa speaking at a forum alongside “Ambition Africa 2024,” a flagship annual event organised by Business France. This year’s event, held in Paris between November 19 and 20, 2024, brought 2,500 participants representing 42 companies across Africa, up by 700 from last year.

No one from Ethiopia showed up at the business meeting in Paris, except for this one lawyer. But over 2,000 business contacts were made between African and French companies.

There was none from Ethiopia, bar Dadimos Haile (PhD), a managing partner of Dadimos & Partners LLP. They have missed what Sophie Primas, France’s minister delegate for Foreign Trade & French Nationals Abroad, described as the “promise of real mutual benefit.”

According to French authorities, more than 2,200 appointments were made in the two days of business-to-business contact.

“It’s important to mobilise French companies to Africa as the continent is crucial to France,” said Marc Cagnard, Business France’s managing director for sub-Saharan Africa. “Africa remains a priority.” President Emmanual Macron’s special advisor on Africa, Jeremie Robert, echoed this sentiment.

According to Robert, Ethiopia remains an important country for France, “demonstrated by the visit of the President in 2019,” the first in 50 years by a sitting French leader.

With its population of over 100 million, French authorities see Ethiopia offers a massive consumer market but acknowledge its struggles with supply-side constraints. Mouti, however, argued that Djibouti could play a crucial role in bridging this gap, leveraging its port infrastructure and geopolitical position to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) into the region.

While two-thirds of Djibouti’s GDP derives from services, including port and logistics operations, Mouti stated the necessity of industrial growth to sustain long-term development.

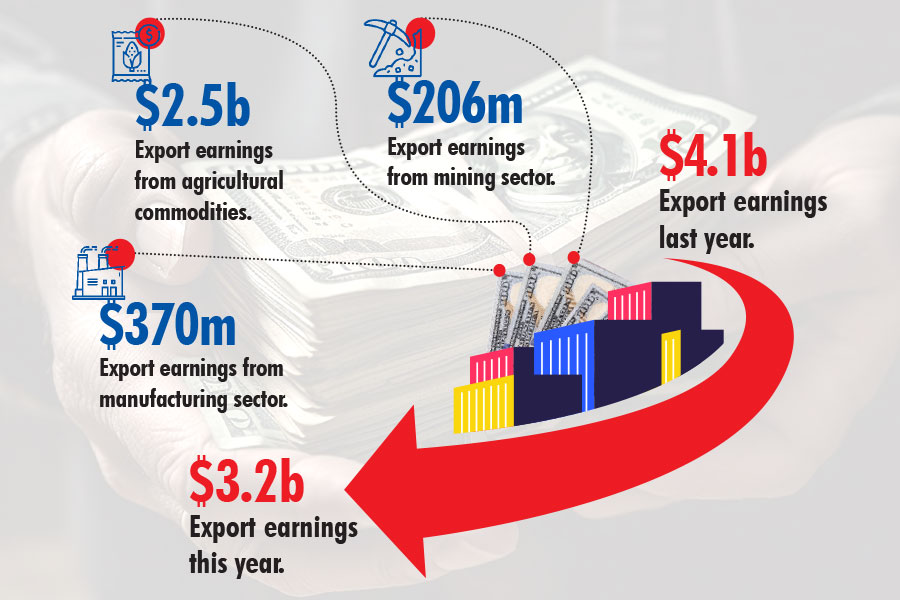

Yet the road ahead is not free of rough boulders. The African continent’s share of global trade remains a paltry 2.6pc, and Mouti blamed systemic imbalances, particularly in trade flows. Exports from the region remain dominated by raw materials, while imports skew heavily toward manufactured goods, creating an enduring trade deficit.

“We need to export less cotton and more T-shirts,” Mouti quipped, urging the importance of value addition.

However, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) promises to unlock a 3.4 trillion dollar market. According to Mouti, this requires not only industrial transformation but also greater investment in human capital. Mouti’s remarks come at a critical juncture for Djibouti and Ethiopia.

The end of the two-year civil war in the north may have sparked hopes of an economic rebound, but the scars of conflict linger, with flaring insurgencies in the country’s two largest regions, Amhara and Oromia regional states. Ethiopia’s foreign exchange reserves were alarmingly low, and inflation continues to erode purchasing power.

The President’s advisor was unflinching in his assessment of Ethiopia’s vulnerabilities, noting that its currency devaluation, over 110pc since it was floated in July this year, remains a major deterrent to foreign investment. But Mouti also expressed optimism, arguing that Ethiopia’s vast untapped potential could be unlocked with the right mix of policy reforms and international support.

“Djibouti and Ethiopia are completing one another,” Mouti said. “We’re creating opportunities together.”

Djibouti has emerged as a relative haven of stability, aided by its strategic location at the mouth of the Red Sea and its role as a host to military bases from the United States to China and other countries. Its dual role as an economic and strategic hub places it at the heart of geopolitical calculations in the Horn of Africa.

“It’s not about presidents and ministers,” Mouti said. “You need functional, working institutions that are able to negotiate, commit, and deliver.”

Central to Djibouti’s strategy is developing renewable energy projects, a move Mouti framed as both a necessity and a business opportunity. Djibouti receives more than half of its electricity from Ethiopia, making energy security a pressing concern. Recent investments in wind and solar power targeted dependence while positioning it as a green energy pioneer in the region. Mouti revealed plans for a 30mw solar power plant, and growing private investments in renewable energy solutions, including solar battery systems adopted by households to offset high electricity costs.

According to Mouti, energy is only one facet of Djibouti’s broader push for economic diversification. He identified logistics and e-commerce as sectors ripe for growth. While e-commerce penetration across Africa remains low, Mouti remains upbeat about digital trade and its ability to transform the continent’s economies.

Transnational companies, including Amazon and Alibaba, may eye African markets, but Mouti urged the creation of local ecosystems to capture the value of this emerging industry. He argued that infrastructure should be adapted to support these developments, including investments in urban mobility to address chronic congestion in African capitals.

Despite Djibouti’s ambitious agenda, Mouti acknowledged that his country cannot succeed in isolation. He called for stronger partnerships with development institutions and private investors to finance critical infrastructure projects.

“Investing in Africa is first and foremost creating a partnership,” he said.

Last week, French authorities reassured their guests that they are willing to redefine their relationship with African countries based on “shared values and risks.”

Minister Primas pledged to reorient this relationship toward vital economic areas such as securing supply chains, adding value in tech and environmental sovereignty, accelerating energy transition, and supporting the youth.

"We need to invest in the human capital, education, and the youth," said Mouti. "The future generations: they’ll be the ones leading and helping us grow."

PUBLISHED ON

Dec 01,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1283]

Fortune News | Mar 09,2019

Commentaries | Jan 03,2021

Films Review | Jun 27,2020

Radar | Jul 13,2019

Fortune News | Feb 27,2021

Fortune News | Sep 21,2019

Fortune News | Jul 01,2023

Agenda | Feb 25,2023

Radar | Feb 22,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...