View From Arada | Jun 07,2020

getachew Shiferaw felt the danger before he saw it. On July 24, 2025, the midday sky above Addis Abeba darkened, and rain began to hammer the capital in sheets. A manager of the OLA gas station café on Menelik II Ave., across from St. Estifanos Church, he sprinted for his Toyota Vitz, hoping to beat the rising water.

“The speed of the flood was sudden,” he told Fortune. “I ran to get my car keys, but by the time I returned, the water had covered everything. I didn’t even change anything.”

The café’s warehouse drowned in muddy water; syrup, sugar and coffee beans were all ruined, costing 50,000 Br. The car’s electronics failed, repairs to the engine control module (ECM) and spark plugs ran 115,000 Br, and a tow truck added 3,500 Br. The insurer refused to pay, calling the deluge a natural disaster.

“Even electric vehicles are stuck in garages,” he said.

He looked at rows of engines silenced by floodwater.

Across town, taxi driver Mulatu Ayalneh steered through another pocket of trouble. For 15 years, he has driven the route from Mexico Square to Saris, yet the stretch near the Bulgaria area has turned treacherous. A maze of potholes fills with standing water, forcing him to crawl forward with hazard lights on.

“When it rains, the steering wheel goes where it wants,” he said. “There’s no good lane, only the least bad one.”

“The rivers had changed from being graceful to a danger.” Endashaw Ketema Head, Urban Beautification & Green Development Bureau Addis Abeba City Administration

A piston once broke there, a memory that resurfaces whenever clouds gather. For Mulatu, the threat is simple. Water rises, touches a battery, and the engine quits. Electric cars face a greater risk.

“Repairs happen,” he said. “But nothing lasting.”

Addis Abeba, home to more than five million people (a data the city administration used despite no official census carried out for nearly two decades), has endured week after week of flash floods that paralyse traffic, submerge homes and shred livelihoods. On Menelik II Avenue, water roared through the parking lots beside the Ghion Hotel, lifting vehicles “like toys” and depositing them metres away.

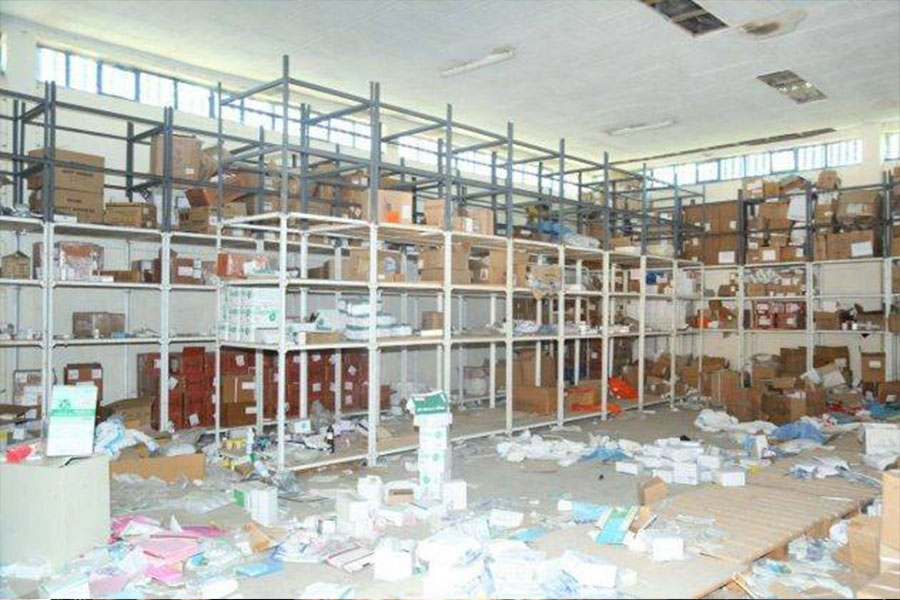

Inside the Riverside Project Office behind the hotel, workers wearing muddied clothes picked through waterlogged files, mud clinging to filing cabinets, refrigerators and toppled chairs.

“Everything is soaked," Getachew muttered, surveying the wreckage. "We don’t know where to start.”

The Addis Abeba Urban Beautification & Green Development Bureau, charged with restoring the city’s rivers, was itself swamped.

“The rivers had changed from being graceful to a danger,” said Endashaw Ketema, who heads the Bureau’s department for watershed and green development.

The same scenes repeated along the Ring Road in the Bole area, as well as in neighbourhoods such as Kotebe and Betel. Cars stalled in the middle of the lane, their headlights dimmed by brown water that covered the entire intersection. Car-wash stations fell silent, and silt stains on walls marked the high-water line.

Wondimu Seta, the city's deputy mayor and its general manager, acknowledged the scale of the problem and announced the establishment of a special task force to address seasonal flooding. His Administration has erected 64 flood-protection walls, in addition to the larger Riverside Project. The task force draws staff and machinery from several departments and districts, closing human-resource gaps and coordinating faster responses.

“We're fixing the century-old problem of poor infrastructure coordination,” Wondimu said.

A new rule prohibits construction within 30mt of rivers, matching the city’s master plan. Yet, damage rolls on.

Abel Temesgen, a 39-year-old businessman, switched from a fuel-hungry Toyota Land Cruiser to a BYD electric vehicle to escape soaring diesel prices. He thought that with diesel prices continuing to rise, he could match the car’s value in a year. Three weeks before he spoke, heavy rain transformed Summit Road into a river. Abel tailed a Sinotruk, thinking the larger truck would part the water.

“That was the first time I believed in a Sinotruk,” he joked.

But when water spilt over the EV’s hood, he pulled over. The car shut down and, weeks later, the cause remained unclear.

“We still haven’t gotten any feedback,” he said. “My mistake was thinking I was driving a Land Cruiser. You have to drive an EV carefully.”

Friends had warned him to buy a high-rider. He now repeats that advice.

According to Eyasu Solomon, communication director of the Addis Abeba City Roads Authority (AACRA), crews repaired more than 483Km of drainage in the past fiscal year, work he believes prevented worse ruin. He blamed the concrete poured in floodplain buffer zones.

“What used to be absorbed by the ground is now blocked by concrete,” he said. “That runoff ends up on roads.”

The Authority is upgrading pipelines from 60cm to one metre in diameter and digging wider trenches. Backed by Japanese technical aid and World Bank funding, city officials are revising the master drainage plan, a 10-year project that faces its primary limitation of financing. Despite a budget of 17 billion Br in the past fiscal year, the Authority exceeded seven billion Birr. It now marked flood-prone “black spots” for urgent attention.

The Bole-to-Gerji and Qaliti-to-Tuludimtu roads were built with drainage in mind, yet many side routes still lack proper systems.

“That is where we’re seeing the biggest challenge,” Eyasu told Fortune.

Girma Hailu, director of cleaning services at the Addis Abeba Cleansing Management Agency, rejects the claim that garbage is the main culprit.

“Our mandate is to clean dry dirt,” he said. “Drainage systems are clogged by wet waste, mostly mud.”

During the flood near the Ghion Hotel, his team rushed in.

“We couldn’t find any of our waste there,” he said. “But, we still provided emergency cleaning.”

He conceded that mud removed from drains sometimes ends up back inside.

“We sweep what’s on the asphalt," he told Fortune. "We collect what’s in every house. But the drainage is closed by mud.”

A recent survey identified 2,594 open manholes, many of which were missing covers due to theft or damage. According to Girma, crews now work four shifts across 48 areas, targeting 3,209Km of roadside with 11,500 staff and 20 night-operating machines.

Rainfall patterns amplify the strain. Addis Abeba receives nearly 70pc of its average 1,400 million-litre annual rainfall between June and September. Droughts bake the soil into hardpan. When the sky opens, little soaks in. Climate models suggest those dry spells could become 53pc more frequent in the two decades beginning in 2040, even as the city already endures about three months of extreme drought each year. The hardened ground, clogged rivers, and swollen streets leave nowhere for water but to flow into homes, shops, and car engines.

The city’s topography offers little mercy. Three rivers — the Bantyeketu, Kebena and Aqaqi — thread through a basin rimmed by hills. The Aqaqi, the largest of the trio and a tributary of the Awash River, once ran 53Km from the highlands to the Aba-Samuel reservoir. Now, researchers call stretches of it “dead rivers,” and the Little Aqaqi, fouled by sewage and industrial waste, is tagged an “open sewer.” Plastic bags bob where fish once swam.

The Aqaqi river system, fed by the Kebena, Kechene and Ginfile streams, once drained vast slopes. Today, much of it is clogged. Kolfe Keranio District has turned riverbeds into dumping grounds, and runoff courses onto roads.

Mamo Kasegn, a hydrologist at Addis Abeba University, argues that patchwork fixes miss the root flaw of design.

“If you look at Shiro Meda and the city’s core, they have different needs,” he said. “Do you think the same drainage system can control the water in both?”

“The drainage system plan is not feasible,” he said, adding that policy, not just construction, is at fault.

City officials argue that Mayor Adanech Abiebie's Administration flagship Riverside Project seeks to reverse this slide, starting with 42Km along the Kebena and Kechene rivers in phase one, reviving more than 600Km of waterways. Plans call for parks, cafés and promenades up to 200mts wide. Japanese engineers have lent equipment and expertise to clear blocked drains and riverside roads, yet financing gaps linger. The city's Roads Authority, for instance, has identified notorious emergencies.

A Mekanisa flood two years ago choked streets with soil. Gurd Shola Bridge was flooded last year until workers cleared the site. Even so, standing water still pools at the location after storms.

Elevation in the capital swings more than 1,100mts from its highest to lowest points, but many blueprints ignore that.

Mamo insisted on models tailored to slope, runoff and manhole spacing, along with new regulations and money. He recalled the floods of 2020, referring to them as natural events exacerbated by human decisions.

Deputy Mayor Wondimu says the new task force will help close such gaps by pooling machinery, skilled workers and rapid-response teams each rainy season. The city has also drafted rules barring construction within river setbacks and promises tougher enforcement. Eyasu, whose crews install larger pipes and map black spots, sees progress. Girma, who sends teams of sweepers and vacuum trucks, sees commitment. Yet, Getachew, staring at his ruined supplies and crippled sedan, waits for proof.

“You fine someone 100,000 Br for damaging infrastructure," Mamo quipped. "But, what happens when someone loses their car or home to flooding? What fine does the government pay then?”

Addis Abeba’s struggle is at once old and new. The geography has always funnelled water toward the basin; the climate has always delivered torrential afternoons. What changed is the city itself, with more concrete, more cars, and more people. Drainage lines designed decades ago buckle against that weight. Policymakers now draft blueprints that promise coordination, modern standards and greener riversides.

However, it is always close at hand, testing roads, engines and promises. It is a fast-growing metropolis, where nature keeps its own schedule, indifferent to man-made plans.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 03,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1318]

View From Arada | Jun 07,2020

Fortune News | Sep 23,2023

View From Arada | Sep 19,2020

Radar | Aug 10,2025

Commentaries | May 23,2020

Fortune News | Sep 19,2020

Fortune News | Dec 19,2021

Fortune News | Oct 05,2019

Featured | Sep 27,2025

Radar | Oct 31,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...