Radar | Nov 23,2019

Aug 17 , 2019

My mother entrusted me with one of our family's prized possessions when I turned 10, a film photo camera. It was a clunky, solid, awkward piece of technology, and I was allowed the privilege of using the last four shots out of the 24 roll of film that already hosted valuable family memorabilia.

Eighteen years have passed, and I still have the photos - of my four friends and me - that I took back then. It hangs on the wall of my parents' house, encapsulating a time well spent.

An intrinsic part of development - personal or sociopolitical - is documentation. At the lowest level, it is documenting every milestone children make as opposed to a time when birth certificates were a rarity. As a nation, it is moving forward from sole-biased documentation of royalty to the importance of each citizen’s personal recognition.

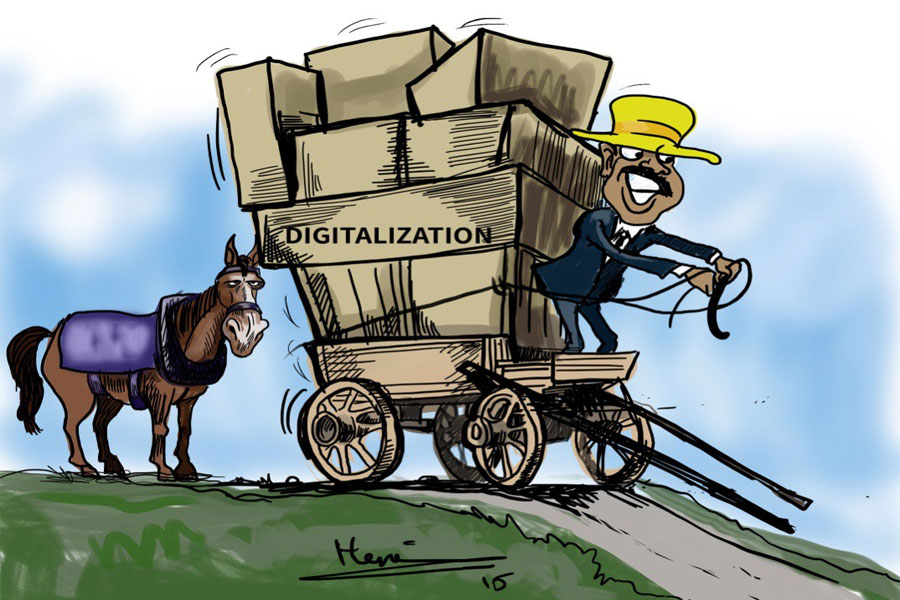

Despite the advances of technology, Ethiopia is a long way off from properly documenting its history. We continually wrestle with irregularly recorded and mismanaged data. Even though most understand the importance of well-documented information, the execution of such initiatives is often inept.

Evidence of this is the recent tree planting initiative known as Green Legacy. The government set out with a plan of having 200 million trees planted in a day, breaking India’s Guinness World record by at least three fold. It was part of the administration's initiative to see four billion trees planted across the country between May and October.

The day of planting took place on July 29, 2019. Within 12 hours, the record was broken, with over 350 million seedlings planted. Yet, all we had for this was the word of government officials, and the media was only subsequently able to report the record with the cautiously optimistic, “according to officials.”

BBC reached out to Guinness World Record, asking if the reported documentation would be published. Guinness World Record simply requested for the representatives of the Green Legacy to get in contact with the proper documentation. So far nothing of this historic initiative has been backed by data, at least not to the satisfaction of the folks at the Guinness World Record or multiple independent observers. This should force us to come to terms with our ill-capacity of doing due diligence in carrying out such momentous tasks.

Regardless, our youth were motivated, and the nation was energised at a chance to make a positive change. Social media was ablaze with encouraging images of Ethiopians uniting for a worthy cause.

For now, we may say that the positive impact is enough. Yet as this was not an exception to a rule, a lack of planning to document the day with internationally acceptable data has failed the country at present, and it might continue to charge a similar price tomorrow. Insightful decisions can only be made when our questions of development are met with the right answers. And the right answer is about having data and well-documented information that can back our position.

The same is true of a recently released Netflix film, The Red Sea Diving Resort, which is also an example of a narrative that has been distorted. This film is based on true events of an Israeli covert operation to smuggle Ethiopian Jewish refugees from Sudan to Israel.

But the film is riddled with stereotypes that plague our identity. It is a story of human triumph turned into a white saviour’s abusive romance with Africa.

Our identity as Ethiopians and Africans is rooted in how we can understand our past and decipher the present.

There is a saying in Ethiopia - yetemare yigdelegn - “better the educated kills me.” Despite the morbid phrasing, it is meant to show that those that are educated, informed and with the correct numbers can make the right decision, even if the worst is to come. It is a belief that if it is at least done with precision, even a terrible end would be acceptable.

So as our "educated" workforce rattles about in a nation desperate for change and growth, the responsibility to adequately document our journeys, losses and triumphs falls in our laps. When we do not record our lived experiences we lose the hold on our narratives. Our truths become secondary to what others document. It means that those who choose to write about our stories will not reference our own voices but the interpretations of bystanders.

Our data matters, our stories matter. They matter enough to be documented, archived and shared.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 17,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1007]

Radar | Nov 23,2019

Fortune News | Sep 10,2023

Radar | Jan 31,2021

Fortune News | Jan 12,2019

Fortune News | Jun 05,2021

Radar | Oct 31,2020

Radar | Feb 26,2022

Viewpoints | Oct 14,2023

Commentaries | Sep 02,2023

Editorial | Jun 10,2023

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...