Advertorials | Jul 24,2024

When the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic brought to the fore the urgency of health services to Ethiopia, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) did not waste time calling for health professionals to serve their country. It was a move that is now being rescinded as the government's response to the virus is readjusted toward the treatment of cases at home instead of treatment centres.

When the Prime Minister's announcement arrived in March, the nation's health professionals did not disappoint. No less than 23,000 health professionals responded, going on to be employed in quarantine and health centres. About a sixth of these were hired on a contractual basis, addressing the paradoxical circumstance of health professional unemployment in a country that direly lacks doctors. This was short-lived. The isolation centres are closing up as the Ministry of Health has begun to lean on self-care at home as an alternative means of treatment.

It has left the country with a unique set of circumstances. On the one side is a lack of employment opportunities for doctors. On the other is one of the lowest ratios of health professionals in the world. The outcome is that Ethiopia has a high incidence of infectious diseases as well as a rising prevalence of non-communicable illnesses such as diabetes.

The discrepancy is explained through a combination of planning, administration and budgetary failures, according to those who know the sector well. Despite being one of the countries in Africa that have pledged to contribute 15pc annual spending to health services, the government is only currently meeting a third of that. Complicating this factor is a language requirement by regional health bureaus that has effectively narrowed down the choices of fresh graduates. Neither is the matter helped by the fact that increasing numbers of doctors are graduating from universities without a corresponding rise in budgeting for health services.

The administration of Prime Minister Abiy is looking for ways to increase funding and engage the private sector to fill the gap, according to Lia Tadesse (MD), minister of Health. But if such options are exhausted, the nuclear option is exporting health professionals instead of allowing their training to go to waste. Health experts that know the sector believe that this should be a matter of last resort and that realigning the outputs between the health and education sectors with spending in these areas is an urgent matter.

You can read the full story here

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 31,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1070]

Advertorials | Jul 24,2024

Fortune News | May 08,2021

Life Matters | Apr 13,2024

Editorial | Aug 20,2022

Fortune News | Oct 02,2021

Commentaries | Oct 07,2023

Sunday with Eden | Jan 13,2024

Radar | Apr 03,2023

Fortune News | Jul 18,2021

Fortune News | Jul 23,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

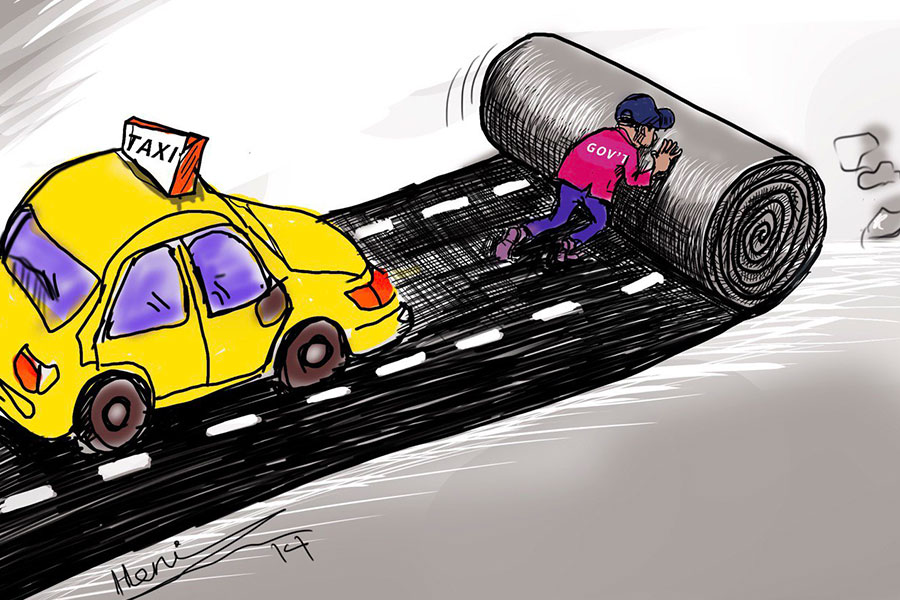

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Nov 1 , 2025

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a statement two weeks ago that appeared to...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...