Fortune News | Dec 14,2019

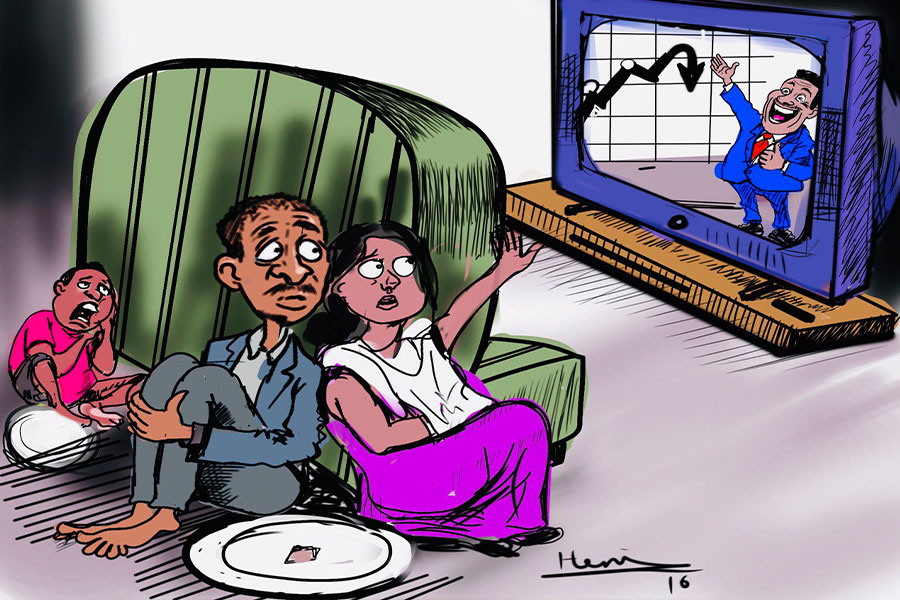

It has been over two years since Abaynesh Rega, a small-time vegetable seller, began struggling to make ends meet. She works day and night selling onions, tomatoes, potatoes and kale to passersby on the wide pavement of a road in the area known as Haile Garment in Nifas Silk Laphto District.

It is the only means of income she has to take care of her three kids, and rest is a luxury she can ill afford. After toiling well into the night at her trade, she needs to tend to her motherly duties before she can catch a wink of sleep. A story like hers is nothing out of the ordinary for the many women who work as vegetable vendors in the area.

A short while ago, a glowing opportunity seemed to present itself to Abaynesh and her colleagues. The construction of a vegetable and fruit market laid its foundation right in the neighbourhood where they worked, although many had to vacate the area due to the construction work.

"Struggling for one month wasn't an issue compared to the advantages, and the doors [the market] could open for so many women like me," said Jemila Mohammed, another small-time vegetable vendor.

Though Jemila and others like her were optimistic initially, the story has so far proven to be a sombre and disappointing one.

Following the onset of the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Atikilt Tera, a vast open vegetable and fruit market originally based in Piassa, temporarily moved to the fields of Jan Meda, a sports ground, to curb the spread of the virus. The market stayed in Jan Meda for over five months. Ultimately, it was given its new home at the Lafto Vegetable & Fruit Market Centre in the Haile Garment neighbourhood of southwestern Addis Abeba. The location seemed to surprise both customers and vendors.

The location is relatively well-suited for a fruit and vegetable market. It affords easy access to basic infrastructure, according to Abdulfeta Yusuf, head of the Addis Abeba Trade & Industry Bureau. "Getting such a plot of land that is relatively near to the city centre is no easy feat," he said.

With a construction period which lasted only a month, the 8,000Sqm market was opened for business in early January 2021. It cost an estimated one billion Birr to build, and space in the marketplace is being rented out at 100 Br a square metre.

The market contains 980 compartmentalised shops accommodating 516 small-scale vendors, 46 distributors and 24 farmers. The stands lie in rows with wide spaces dividing the sections. It has a large parking area and is well-secured with constables guarding the compartment rows. The market opens at 6:00am and closes around 7:00pm.

The construction of this vegetable market has created jobs for more than 2,000 people. This includes caretakers and those who worked loading and unloading produce at the previous market in Jan Meda, as well as 100 waste collectors hired to keep the area clean.

Waste collectors are on duty to keep the market clean during working hours.

One of the motives behind this project is to give a platform to women with small-time vegetable selling businesses, according to Adanech Abeibei, deputy mayor of Addis Abeba, speaking at the inauguration of the Centre a few weeks ago.

However, behind the shops, there is an abandoned plot of land fenced off with corrugated iron sheets where small-time vegetable vendors like Abaynesh and Jemila have settled in makeshift stalls with plastic tarps over their heads for shade.

They relate that promises they had received from officials about the allotment of space in the new market have yet to materialise.

It is an unpleasant prospect that faces the small-time vegetable vendors who are struggling to cope. They are not allowed to sell during the daytime with guards patrolling the market to make certain of it. They are forced to work at night and in the early morning to afford their daily bread.

"It's tough to fight injustice when regulations tie both your hands," remarked Senayit Awelachew, one of the struggling vendors.

The issues are exacerbated by the fact that most vendors carry identification cards from Oromia Regional State. To organise themselves into a legally recognised association or union, they need to carry identification from a kebelein Addis Abeba. And since kebelesare not currently distributing new identification cards, they are unable to work.

"We were excited to have a horse in the race, but we didn't get anything we were promised even though we have been paying our taxes and delivering on our duties," a frustrated small-time vendor mentioned. "We were asked to rent a tent for 500 Br and a shop for around 1,500 Br to 2,000 Br a day."

On the contrary, in the opinion of Getnet Yawkal, an expert on corporate and commercial law, paying taxes and settling in an area for a long time does not grant either property rights or the right to ask for it.

"In Ethiopia, the land belongs to the government," said Getnet. "Without evidence that shows their ownership, it's a far-fetched argument."

The government itself insists that it is mobilising to help these women.

"We've already identified a working space for them and immediately started the construction," said Abdulfeta. "It will be completed in a short period of time."

Another point of concern is that when the market was located in Jan Meda, large numbers of vendors worked without business licenses, according to the Bureau head. The fact that the new vegetable market does not allow these clandestine small-scale vendors to operate is a source of deep concern for them, and they are demanding solutions from the government.

The legalisation of these small-time vegetable sellers is being assessed, and 380 of them are in the process of being legalised, according to Abdulfeta.

The legal vendors and distributors working in the market also have their share of dissatisfaction.

"Even though the modern arrangements are good, the far-off location drives away many customers," mentioned a distributor who wished to remain anonymous. "I've lost over 40,000 Br due to the market's inaccessibility and the lack of people that used to help us in loading and unloading our produce."

Abdulfeta Aziz, a distributor, mentioned that he used to sell at least 10ql of onions every day when the market was in Piassa.

"Now we barely sell two quintals," he lamented.

Abdulfeta, who says the far location of the centre limites customers from visiting the area, claims that he sells a maximum of three quintals of tomatoes a day. In contrast, he used to sell between nine and 11 quintals a day in Piassa.

There are other problems too, with a lack of adequate space being a big one. Evidently, the vendors who own their own shops use some unorthodox methods to make some extra money. If one vendor gets a large product delivery and lacks the space to store the goods, another vendor will temporarily rent out some space to them and charge as much as 2,000 Br a day.

"The structure is completely missing the necessary outlets for our products, and we are losing money over it, with our products lying around on the pavement," said one vendor. "It's like leaving a lump of meat on the floor and expecting to sell it afterwards. We're selling at reduced prices to attract buyers."

However, some are pleased with the new market, viewing it as a glass half full. Vendors coming from Qera are particularly content.

"The market here is preferable, since Qera was an expensive area to sell at," stated Girum Ayalew, a vendor from Qera. "But now it's extremely cheap, the vegetables we receive cost less, and the variety of products coming in is better."

Girum added that the electricity infrastructure is adequate, an important factor since the fruits and vegetables are delivered and stocked late at night.

Similar fruit and vegetable market projects were implemented over a year ago, including the markets in Furi and Jemo. However, due to disappointing results and poor maintenance, many vendors chose to leave the markets. Part of the reason for this is that the markets were not promoted well, and there was a lack of customers. The Bureau maintains that these markets are getting a second chance after being renovated and reopened.

"The new traders showing interest as well as the capacity to provide different industrial and agricultural products in a fair amount are lifting up the market now," said Abdulfeta Yusuf, the Bureau head.

Building one or two markets is not enough, according to Zegeye Chernet (PhD), assistant professor and deputy director at the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction & City Development.

The markets were in the city centre, which can make the city more crowded. Since Addis Abeba has a complex transportation system, the way to solve the problem is to decentralise the market, according to the expert. He recommended building a market for every district so that customers and sellers would not have cost and transportation difficulties.

"One of the reasons for urban planning is to integrate location, time and activity in the urban area in order that it will create a pattern and eliminate unnecessary hustle," he said.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 30,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1083]

Fortune News | Dec 14,2019

Fortune News | Dec 17,2022

News Analysis | Sep 26,2021

Fortune News | Apr 30,2021

My Opinion | Sep 24,2022

Radar | Feb 20,2021

News Analysis | Jun 24,2023

Radar | Dec 26,2020

Fortune News | Sep 30,2023

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transportin...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

The cracks in Ethiopia's higher education system were laid bare during a synthesis re...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Construction authorities have unveiled a price adjustment implementation manual for s...

Jul 13 , 2024

The banking industry is experiencing a transformative period under the oversight of N...

Jul 20 , 2024

In a volatile economic environment, sudden policy reversals leave businesses reeling...

Jul 13 , 2024

Policymakers are walking a tightrope, struggling to generate growth and create millio...

Jul 7 , 2024

The federal budget has crossed a symbolic threshold, approaching the one trillion Bir...

Jun 29 , 2024

In a spirited bid for autonomy, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), under its younge...