In-Picture | Jan 27,2024

May 16 , 2020

By Kinfe Yilma (PhD)

At first grudgingly, but later prompted by the current crisis, which brought tech to centre stage in public life, the reform agenda has also permeated the cyber realm. Bills meant to regulate behaviour and activities in cyberspace are mushrooming, bringing with them problematic provisions, writes Kinfe Yilma (PhD) (kinfe.yilma@aau.edu.et), assistant professor of law at Addis Abeba University.

Reform has perhaps been one of the most overused and abused terms under the Ethiopian sky for the past two years. It seems that almost every point of policy is up for grabs by over-eager reformers.

The hype is just as pervasive in the legal arena. The nation embarked upon the task of revising many areas of law at once. Working groups of sorts churned out several draft pieces of legislation one after another under an ambitious programme of overhauling the nation’s statute book.

At first grudgingly, but later prompted by the current crisis, which brought tech to centre stage in public life, the reform agenda has also permeated the cyber realm. Bills meant to regulate behaviour and activities in cyberspace are mushrooming.

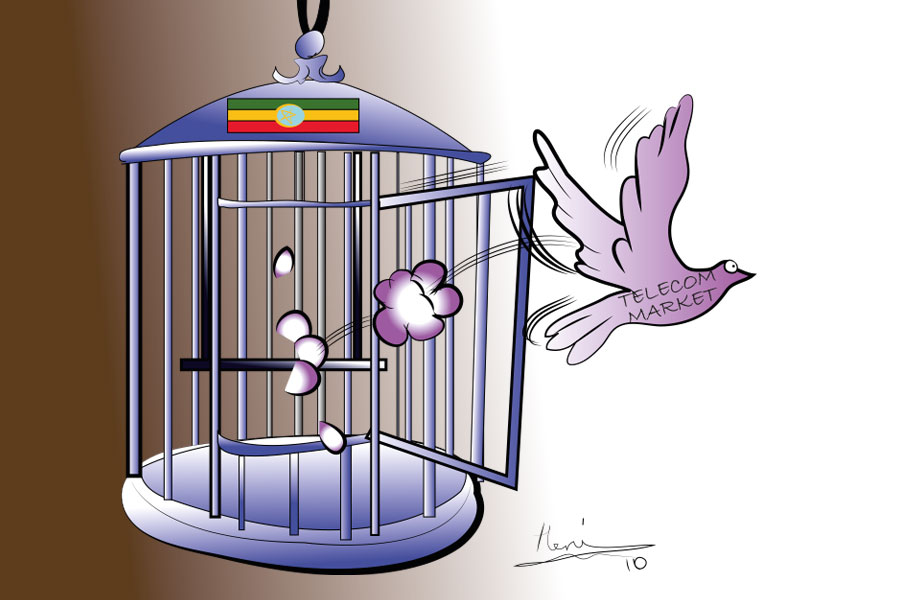

In addition to a new cybercrime bill, pieces of legislation governing the processing of personal information (data protection law), telecoms and electronic transactions are now being rushed for legislative imprimatur. No doubt, it is a long overdue task to make the nation’s legal system fit for purpose in the digital age. But it is also critical that the reform agenda, particularly in the field of cyberlaw, is fashioned carefully and pursued in a nuanced manner.

A feature of the nation’s legal reform programme is the tendency to short-circuit the legislative process. The question of whether, and the extent to which, the reform programme and its processes were inclusive and transparent remains controversial.

It is hard to forget, for instance, how the Communication Services Proclamation, which established the Ethiopian Communications Authority, was adopted at the speed of light with little input from stakeholders. A highly consequential piece of legislation such as this warranted elaborate consultations. Rushing legislation does not just undermine its legitimacy and hence effectiveness but also its juridical quality. The quality of any piece of legislation hinges on its gestation period and the level of stakeholder consultations.

The data protection bill is a case in point. While the idea of enacting such a law has existed since the late 2000s, the draft that came out a decade later falls short in many ways. The bill fails to fully align its standards with important international and regional instruments such as the AU’s Malabo Convention and the Council of Europe’s Data Protection Convention.

One notable example is its failure to enshrine widely accepted exemptions for the processing of personal data for journalistic and literary purposes as well as domestic processing activities. Compounding the problem is the concern that the bill appears to be considered in isolation of other existing and upcoming bills.

The Communications Authority’s recent draft consumer rights directive essentially introduces sector-specific data protection standards, but it is unclear how the two pieces of legislation would interact.

This becomes more precarious when one considers that the former’s conception of consumer data privacy is deeply ambiguous and downright inconsistent with the latter. The directive speaks of "protection of consumer information" in the context of consumer data privacy, a notion that would stretch the scope of data protection law way beyond the protection of personal data. Its data breach notification standards are also at odds not just with the data protection bill but also with widely accepted international standards.

Another aspect of the problem is regulatory confusion and duplicity. The newly installed Communications Authority, for instance, is bestowed with powers that overlap with other federal entities. It overtakes key policy functions of the Ministry of Innovation & Technology, including advising the government on communication policy and legislative issues. With new powers of vetting communication equipment before being hooked on the telecom network, and "ensuring e-commerce through the use of e-signatures," the Authority duplicates the role of the Information Network Security Agency. Such lapses appear to flow from overly rushed drafting exercises conducted in information silos.

Modern reformists place much emphasis on the need to align the nation’s laws with human rights standards. This has led to what I call the "over-humanisation" of the statute book where human rights are overly ventilated in legal discourse. One needs not mention any examples here other than the drafted cybercrime legislation, which, due in part to its undue over-humanisation, has lost its direction. Ironically, some of those bills crafted under the shadow of this human rights rhetoric raise serious human rights concerns.

The recently adopted disinformation legislation - besides its insurmountable practical challenges - threatens the right to freedom of expression. Recent telecom laws likewise open the doors for unreasonable interference with the right to privacy. Consider the Communication Services Proclamation, for example, which mandates the creation of a National Subscriber Registry based on SIM card registration. It leaves it to the Authority to determine what type of personal information would be stored in the directory.

It further allows the Authority’s inspectors to conduct warrantless searches and seizure of documents and equipment. In a direct affront to procedural justice, the same law allows the Authority to revoke a license if a licensee resists a court order to provide access to its networks for purposes of criminal investigation.

The Authority’s recent draft consumer rights directive, ironically enough, contains less human-rights-friendly provisions. Among other things, it appears to sanction an indefinite data retention period. While it appears to set a one-year cap, it mandates retention of personal data as long as the customer stays with a telecom operator. Worse, it appears to permit limitless retention if doing so would serve the commercial interests of an operator as opposed to the privacy interests of its customers.

What seems to drive the recent overboard behaviour in cyber lawmaking is the firm belief that law is anything more than a tool in this venture of regulating cyberspace and building a digital economy. And that it must be marshaled toward that goal as soon as possible. Needless to say, law cannot be a magic bullet, nor can half-baked legislation cut it. The urge to go paperless, contactless or tame rogue behaviour online will only last until the next policy hype overtakes us, unless reformists pursue a measured, coherent and realistic approach to cyber legislation. And it must go beyond the aspirations of a limited group of elites.

PUBLISHED ON

May 16,2020 [ VOL

21 , NO

1046]

In-Picture | Jan 27,2024

Fortune News | Feb 18,2023

Radar | Dec 12,2020

Commentaries | Oct 31,2020

Viewpoints | Jan 23,2021

Editorial | Jan 15,2022

Sunday with Eden | Dec 04,2021

Viewpoints | Jan 03,2021

Editorial | May 29,2021

Viewpoints | Sep 04,2021

Photo Gallery | 174664 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164887 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 155105 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136703 Views | Aug 14,2021

Editorial | Oct 11,2025

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...