Residing in a country with no capital market, an organised marketplace for trading securities and shares, Bereket Haile, 32, uses social media platforms to buy and sell shares, particularly banks. He finds they have a higher rate of return than most other sectors. Having a background in civil society work, he has over 22,000 network connections on Linkedin.

When the financial sector was flooded by new entrants rushing to join the banking industry, Bereket did not hesitate to react quickly. He had hoped to make a profit when the value of the shares appreciates. He acquired stakes in eight banks that were under establishment since the beginning of last year.

Bereket has a strategy, although constrained by his financial limitations, unlike equity investors where capital markets are developed. Bereket subscribes to the minimum amount of shares during the formation process and buys more once the bank starts operations. Luckily for Bereket, this strategy seems to be paying off. All but one of the eight banks he bought shares in have succeeded in meeting the central bank's upgraded minimum paid-up capital requirement.

One of the success stories is Rammis Bank, where Bereket bought shares a few weeks ago as part of the final round of sales. The Bank's promoters called a general assembly earlier this month, signalling their meeting all requirements. They were ready to join the industry with a paid-up capital of 724 million Br of the two billion Birr subscribed.

Says Bereket: “I was relieved.”

In March this year, in the aftermath of a series of directives introduced by the central bank, regulators declared all banks under formation would have a six-month window to raise half a billion Birr in paid-up capital. They are also required to increase their capital to five billion Birr in seven years, with five years allotted to the banks already in business.

Many of the 18 commercial banks welcomed the change, their executives being bullish about meeting the requirement.

Industry giants such as Awash, Dashen, the Cooperative Bank of Oromia, Hibret, and Nib banks had already surpassed the five billion Birr mark by the end of the third quarter of last year. Others like Abyssinia, Wegagen and Oromia International Bank are only a few million short. Some of the third-generation banks, including Addis International, Debub Global, and Enat banks, are in good shape to meet the requirement before the deadline. Though they have yet to attain half the required capital, their management teams are confident five years is ample time to do so.

The new entrants are trailing behind.

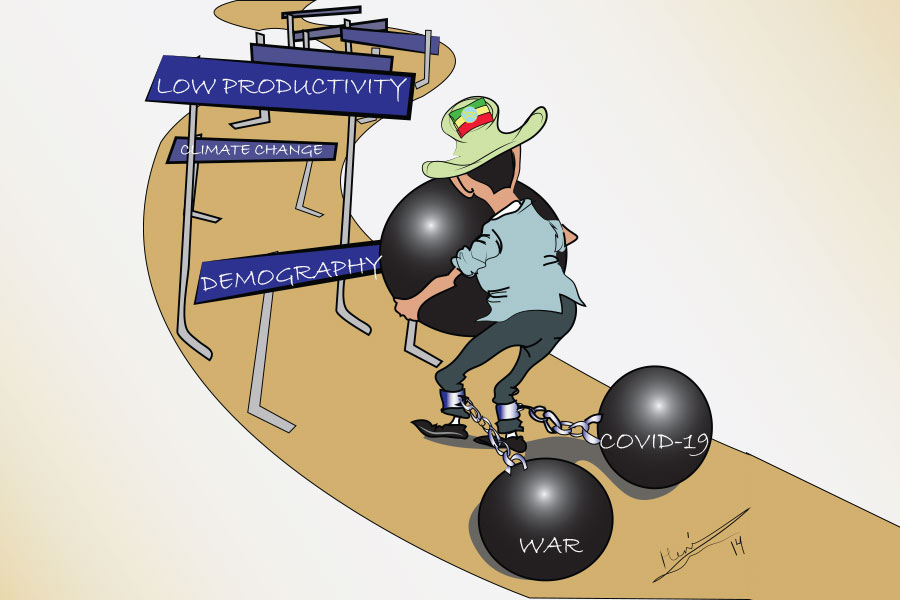

Promoters are frustrated, confronted with a myriad of troubles from the COVID-19 pandemic – an unexpected event that forced them to temporarily halt selling shares – to widespread instability and a full-blown war turning away prospective investors. This can be startling considering the appetite for investments in the financial sector, where shares can fetch as much as 40 times their par value during auctions.

Junedin Sado serves as a promoter for Sheger Bank, one of the hopefuls which have failed to meet the central bank's requirements. A former chief of the Oromia Regional State and Minister under Meles Zenawi's cabinet, Junedin returned from exile following the coming to office of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD).

The prospect of raising half a billion Br in capital was made even more difficult for hopefuls gearing up to join the banking industry by the flooding of shares in the market. Operational commercial banks, such as Hibret, whose new headquarters are pictured above, are also vying to meet the central bank's requirements.

When he and his colleagues began approaching prospective investors, Junedin hoped to raise as much as one billion Birr. But materialising plans was anything but simple. They were not able to meet the half a billion Birr threshold, let alone making great strides. They have their reasons, though.

"Central bank officials don't listen to us, though we're facing a series of problems," Junedin told Fortune. "Although many in the diaspora pledged to invest 20 million dollars, they've changed their minds, uncertain about the situation in the country."

Neither is the revised law helpful in luring members of the diaspora. Although it created room for foreign citizens of Ethiopian origin to get involved in the financial sector, they can only buy shares in foreign currency but receive dividends in Birr.

Promoters of Ge'ez Bank blame these restrictions for failing to raise the equity before the deadline last week. Although they had expected to raise well over the required capital, 310 million Br in paid-up capital was raised thus far.

"The first thing members of the diaspora ask is whether dividends are paid in foreign currency," said Line Kinfe, marketing manager at Ge'ez.

The competition in the primary equity market is cutthroat. A flood of shares is available in the market. Dozens of banks, including those already in the market, have floated shares following the central bank's directive in March this year.

"It created fierce competition," says Line.

He has not given up yet. As the deadline approached, Ge'ez and several others filed a request with the regulators at the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), pleading for an extension. Their attempt was for nought, however. It was rejected outright.

Filed a month before the deadline, it was a request unlikely to receive a response in affirmative, according to Solomon Desta, vice governor of financial institutions at the central bank.

Promoters are less than pleased, blaming the central bank for foregoing consultations with them when the directive was first issued.

"We should have been consulted," said Junedin, whose Bank was gearing up to enter the industry with a focus on catering to the manufacturing sector.

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) issued a directive compelling banks to increase their paid-up capital to five billion Birr six months ago.

Though there were attempts to undertake mergers as a last-ditch effort before the deadline, none were proven fecund.

The promoters of Zad Bank, hoping to join as interest-free service providers, were the closest to attaining a merger before a deal fell through. They had placed their hopes in Rammis Bank, but the deal fell through at the last minute. They submitted a letter to the central bank informing regulators of their decision to dissolve and return the 80 million Br equity collected back to those who invested.

Frezer Ayalew, director of banking supervision at the NBE, expects more such letters to arrive at his desk.

Nearly a dozen banks under formation have to decide whether to continue selling shares to the public, aiming to raise the staggering minimum threshold of five billion Birr, dissolve, or complete a merger. Those who choose to continue raising equity face an uphill battle as economic hardships persist and prospective investors are wooed by banks already operating.

Damota, Jan, Afro, Akufada, Selam, Sheger, Diaspora, Kush, Hadiya and Huda banks have their promoters facing this dilemma. But the key to meeting the requirement will be devising an effective marketing strategy, according to Line, who says Ge'ez Bank is up to the challenge.

To experts, mergers would be the more realistic option to take.

Abdulmenan Mohammed has been one of these experts keenly following the Ethiopian financial sector's path for close to two decades. He foresees raising five billion Birr in capital would be very challenging for newcomers.

"It'd be better to encourage mergers," said Abdulmenan.

It may not be that simple. A merger is a complicated prospect as promoters would have to agree on fundamentals before persuading shareholders to buy the option.

A dozen banks are lined up to join the market in the coming year, with half of them being microfinance institutions (MFIs) ready to make the transition. Addis, Oromia, Sidama, Omo, Somali and Amhara have already submitted their proposals to the central bank. Since all have exceeded the paid-up capital threshold, their management teams have little to worry about on that front. The central bank allows these institutions to complete the transition for two years while compelling them to maintain a certain level of microfinance service even after becoming banks.

"We aim to serve those seeking microfinance services as well as banking," said Damtew Alemayehu, president of Addis Credit & Saving S.C., which submitted its proposal to the central bank earlier this month.

Addis Microfinance gears up to join the industry with nearly four billion Birr in paid-up capital.

Abdulmenan observes the transition would create a significant gap, removing a source of financing for micro and small businesses.

Though the number of new entrants may seem high, it remains inadequate to the country's population nearing 120 million and the lag in financial inclusion.

A study conducted by the World Bank in 2017 identified that only 26pc of Ethiopian save formally with financial institutions, although 62pc of have reported saving money in the previous year. During the same period, 41pc of those surveyed borrowed money, but only 11pc borrowed from financial institutions. Neighbouring Kenya, home to the biggest banks in the East African market, has 30 banks serving a banked population of nearly 40 million.

Abdulaziz Ali, 24, knows an awful lot about the banking industry despite never having opened an account in his life. A computer science graduate, who lives in Kombolcha in the Amhara Regional State, Abdulaziz has never had good reason to deposit despite half a dozen banks operating in his neighbourhood.

"They often ask me to open an account," he said.

Abdulaziz refuses to oblige, convinced that the banks do have little to offer.

The average interest on savings is seven percent, while inflation hit 34pc last month, bringing the real interest rate to negative 27pc. Perhaps the industry will be incentivised to present more enticing products and offers to the unbanked, such as Abdulaziz.

The level of competition will intensify, particularly among the smaller and new banks to set foot in the industry, according to Abdulemenan.

"This may make getting a decent return challenging over a short period," said Abdulmenan.

Central bank officials focus on the positive aspects, convinced that the coming of new banks fosters more competition.

"The finance supervision at the central bank will have to strengthen itself accordingly," Frezer said.

PUBLISHED ON

Oct 16,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1120]

My Opinion | Dec 19,2021

Editorial | Oct 30,2021

Fortune News | May 24,2021

Exclusive Interviews | Oct 15,2022

Radar | Feb 29,2020

Fortune News | Feb 19,2022

Editorial | Sep 26,2021

Commentaries | May 08,2021

Radar | Jun 21,2021

Films Review | Nov 16,2019

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...