Federal legislators recently summoned Shiferaw Teklemariam (PhD), head of the Disaster Risk Management Commission (DRMC), to explain a new bill designed to streamline the country’s response to emergencies. A defining part of the bill is the introduction of a national fund, financed through 17 distinct ways, that promises to boost the country’s capacity to withstand disasters, including drought, floods and locust swarms.

Shiferaw, appearing before members of Parliament’s Standing Committee for International Relations & Peace Affairs, defended the bill as a means of preserving “dignity, independence and sovereignty.” Yet his pitch inevitably reckoned with a far more disruptive act of aid withholding by the United States. President Donald Trump’s January executive order suspending 90 days of foreign assistance was a shock that saw 5,200 contracts cancelled worldwide and froze 83pc of USAID programmes.

Ethiopia, which received 806.5 million dollars in American aid last year, was particularly exposed. Last year’s funding of 1.2 billion dollars made it the largest aid recipient country in Africa, followed by DR Congo and Somalia.

Washington’s waiver system, intended to shield “lifesaving” projects, only compounded the uncertainty. While food aid was exempt, warehouse fees and driver salaries were not; nutrition programmes won approval, but the supply chains for therapeutic foods did not. Even projects granted waivers were throttled when payments stalled. By February, not a single dollar had reached its destination.

The human cost was swift and brutal. In Afar and Oromia regional states, cholera cases surged past 27,000 as water and sanitation schemes ground to a halt. In Tigray Regional State, over 100,000 displaced people went without water. Health bureaus across the country laid off more than 5,000 public workers, including 10,000 data clerks vital to HIV programmes under PEPFAR, an American support programme launched by President George W. Bush. An estimated half a million patients faced interruptions in their antiretroviral treatments.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which rely on USAID for up to 70pc of their budgets, suspended operations. Sadly, early warning platforms such as FEWS-NET went offline, leaving aid workers without the usual maps and data to respond to crises.

This episode revealed the bitter truth that foreign assistance, however generous, can be unpredictable and politically contingent.

Long a linchpin of American humanitarian engagement, Ethiopia found itself abruptly vulnerable. Legislators were thus right to question why a new federal bureaucracy should be layered atop existing agencies rather than streamline and reinforce them.

Since its elevation to cabinet level under a regulation passed in 2015, under Hailemariam Desalegn, the Disaster Risk Management Commission has been tasked with building a national reserve, financing emergencies independently, and even extending aid to neighbouring countries. Its guiding principle, earmarking three percent of the federal budget, roughly 45 billion Br, for disaster responses, sounds ambitious. Yet, it rests on a precarious foundation.

After the largest drought in the mid-2010s, when close to 15 million Ethiopians depended on food aid, the treasury drained 1.4 billion dollars and sacrificed an estimated 16pc of the federal budget, resources large enough to fund every public university for two years. A decade later, the cost of a severe drought has risen to 1.6 billion dollars. Rehabilitating citizens affected by floods demanded 163 million dollars, and fending off locusts another 240 million dollars. Despite this, the Commission’s own reserve is emptied by September each year.

Established in 2000 with 199 million Br, the Prevention & Rehabilitation Programme has depleted half its capital and never been recapitalised. Parliament budgets 1.7 billion Br annually for early warning bulletins, rapid response and reconstruction, while actual spending has averaged 14.7 billion Br, exceeding allocations by more than sevenfold. Last year, the three core relief schemes were budgeted at 26 billion Br but closed at 31 billion Br, topped up by emergency reallocations and donor cheques.

Indeed, grants have averaged 714 million dollars annually over the past decade, spiking above one billion dollars during the pandemic-locust-conflict trifecta of 2021. However, donor appeals remain lumpy and lag behind the crises they seek to address. In the two years beginning in 2021, conflict, drought and floods displaced nearly nine million people; a swarm of locusts stripped more than 400,000hct of crops and pasture. In 2021 alone, 5.38 million people were internally displaced, the highest yearly total ever recorded.

This pattern of hand-to-mouth budgeting has deep costs. Ethiopia spent a fifth of its health budget on emergency nutrition in 2015/16; repeated shocks have shaved an estimated 0.5 percentage points off annual GDP growth, diverting capital from roads, schools and clinics. Donors still foot more than 75pc of relief costs, and funds typically arrive only after a crisis peaks, which is too late to safeguard livelihoods or prevent asset loss.

One notable exception is the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP), launched in 2005. Six years later, its contingency window delivered cash and food to eight million people within weeks of drought warnings. Yet, the Programme depends heavily on external funding. Its reserves pale compared to a climate crisis that shows no sign of abating.

Climate models warn that, without adaptation, Ethiopia could lose up to seven percent of its agricultural output by 2030. Meanwhile, the population grows by two million yearly, stretching food imports and draining reserves. Feeling their own budgetary strains, donors trimmed pledges by 450 million dollars in 2024, citing crises from Gaza to Ukraine.

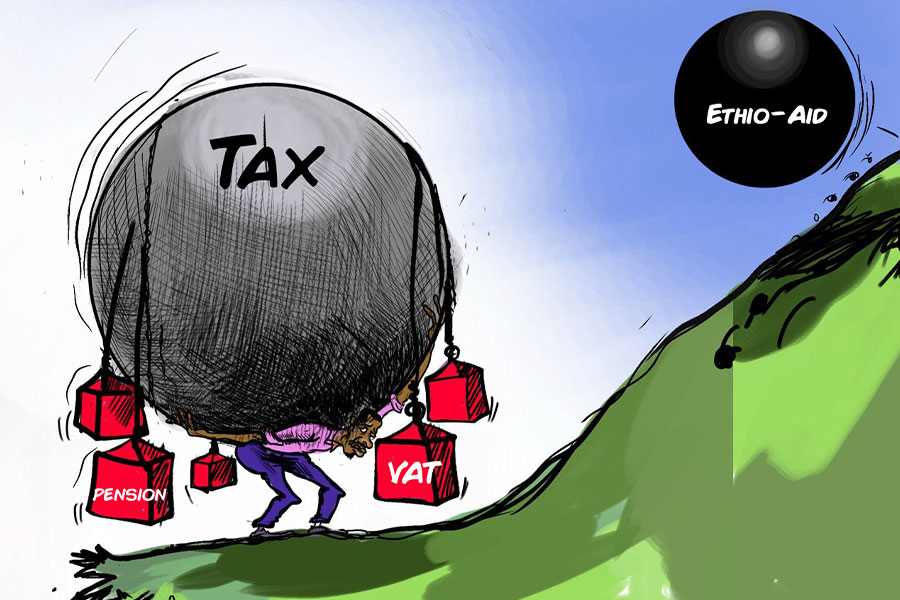

To break this cycle, federal officials hope to raise close to 10 billion Br annually, a tenfold increase on current domestic outlays. Sceptics warn citizens already squeezed by double-digit inflation may baulk at fresh deductions. However, policymakers’ warning that the alternative is far costlier should be understandable. Money, however, is only part of the solution.

Technical capacity lags far behind ambition. Ethiopia boasts Africa’s oldest national early warning system, issuing village-level rainfall forecasts months in advance. In the 2020 drought, warnings reached district offices even as grain lorries remained idle; centralised procurement delayed truck dispatches by six weeks. Regional bureaus, often understaffed and siloed, lack logistics capacity and remain tied to health and agriculture ministries for equipment.

Scaling up the PSNP with parametric insurance, securitising part of the Fund’s revenue, and inviting the diaspora, whose remittances topped 5.6 billion dollars in 2024, to co-invest could be ideas worth exploring. The government’s first Risk Financing Strategy, covering the years between 2023 and 2030, nods to such instruments but lacks concrete deadlines for implementation. The new strategy plans to substitute improvisation with insurance.

Low-cost contingency funds would handle common floods; a World Bank catastrophe deferral credit of up to 317 million dollars would cover medium shocks; sovereign insurance and budget cuts would address megadroughts costing more than 1.5 billion dollars.

Over the past seven years, Ethiopia has spent an average of 31 billion Br annually on disaster responses, more than its external debt interest bill. Every Birr precommitted to drought relief can remain in classrooms, hospitals, and factories. And in a world where aid is no longer guaranteed, domestic financing is not merely prudent. It should be indispensable. The dilemma remains how to finance it.

Four steps could stand out as urgent.

Plug budgetary leaks, requiring each ministry to tag and publish climate-related spending, exposing chronic underbudgeting. This can be complemented by capitalising on the disaster reserve. A one-off injection equal to one percent of GDP, about 1.2 billion dollars, would underwrite average annual humanitarian bills. Buying time with insurance, subsidies can be funded by shaving two percentage points off rehabilitation overspending. Lastly, nurturing the domestic insurance market, boosting reinsurers’ retention limits, establishing an independent regulator and issuing catastrophe bonds can help.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...