The Federal Supreme Court has unveiled a sweeping plan to digitise the judicial system, marking one of the most ambitious overhauls in its modern history.

Branded as “eCourt Ethiopia,” the initiative seeks to transition virtually every aspect of litigation, from filing to verdict, into a digital ecosystem by August 2026, with a pilot phase slated for September this year.

The e-justice system will initially absorb civil cases, gradually expanding to include high profile criminal cases once its cybersecurity infrastructure, developed in partnership with the Information Network Security Administration (INSA), is deemed adequate. According to people familiar with the project, exceptions will initially be made for cases involving national security or the gravest crimes.

Vice President Office Head, Judge Abebe Solomon, called the transformation “game-changing,” noting that 200 federal courtrooms will benefit and that at least one smart courtroom will be installed in each regional and district court office.

At the heart of this transition lies a profound structural redesign of court processes, supported by a hybrid approach that combines in-house reforms with interagency cooperation. The judiciary has earmarked nearly 2.2 billion Br for the three-phased transformation, positioning Ethiopia to join a small cadre of African countries with integrated digital justice systems.

The groundwork for eCourt Ethiopia was laid in 2023 with the development of a wide-area network in collaboration with the state-owned Ethio telecom, a project now reportedly 90pc complete at a cost of 1.8 billion Br. The backbone infrastructure addresses longstanding issues of connectivity, bandwidth limitations, and system resilience across federal and regional courts.

The second phase introduced automatic transcription technology, developed in collaboration with the Ethiopian Artificial Intelligence Institute (EAII), to mitigate procedural delays associated with manual note-taking. Thus far, five “smart courtrooms” are installed at the Federal Supreme Court, with an additional 10 rooms in the Federal High Courts and First Instance Court. The transcription software was delivered at 15.8 million Br, while courtroom equipment cost another 15 million Br just for the five “smart courtrooms.”

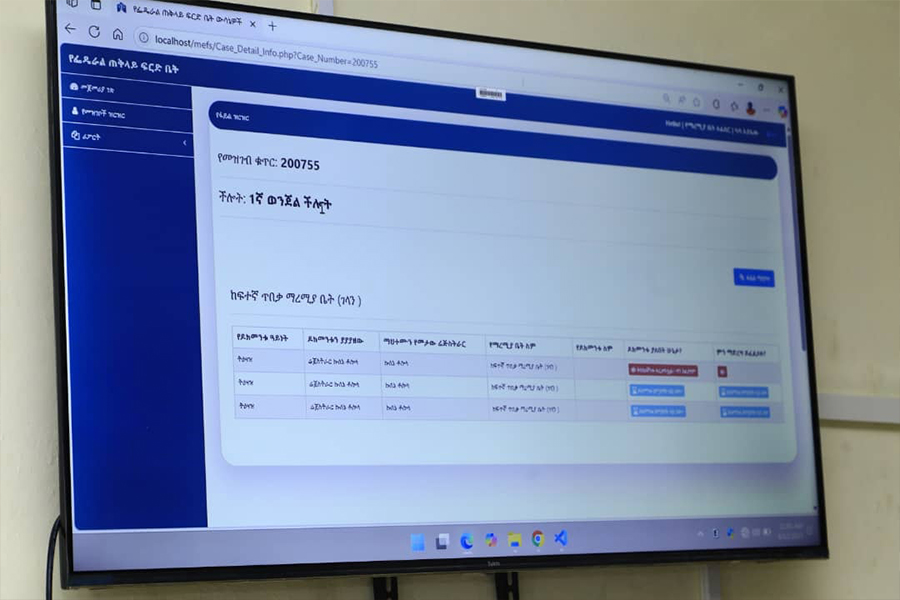

The third and ongoing phase sees INSA spearheading two central digital platforms: the Integrated Court Management Information System (ICMIS) and an Electronic Records Management System (ERMS).

Together, these systems are designed to allow judges to manage cases, issue summons, and handle documentation entirely online. Historical archives, including court records dating back over a century, are being scanned for digital preservation. Scanning at the Supreme Court is reportedly complete, with First Instance Courts underway.

Under the new system, law firms, individual attorneys, and legal service providers will be required to register through the Supreme Court’s portal or in person. Access to the complaints and litigation system requires a formal request to the Chief Registrar, and strict identity verification procedures are in place.

Litigants will submit materials through a new filing and litigation system, which enforces a 30MB total package cap (five megabytes per document), although exceptions will be made for large files. Submissions are acknowledged via SMS confirmation, and paper filings will be digitised where necessary.

Virtual hearings will adhere to the same decorum and procedural standards as in-person trials. All proceedings will be streamed in real time, though only the courts record or distribute audio-visual content. Judges may designate government service centres as access points for those lacking internet access or technological literacy.

“This initiative will speed up justice and cut down months or even years of delay,” said the Vice President.

Court records will be access-controlled, viewable only by the relevant judiciary. After the statutory retention period, records will be handed over to the National Archives & Library Agency, with redacted public versions safeguarding sensitive personal data.

Legal technology entrepreneurs and academics have lauded the initiative’s long-term potential.

According to Yeshwas Eyasu, founder of Five Square Software, reduced litigation costs and greater efficiency are achieved, citing over 12,000 documents already uploaded to his platform, “Ethiopian Legal Tech.”

“It’s a positive step,” he told Fortune. “But, it needs constant monitoring with a 24/7 specialist.”

The Vice President acknowledged that while some regional court offices and prisons already use parts of the system, wider integration is necessary.

Veteran legal advocate Belay Ketema foresees regional benefits. Lawyers in regional capitals such as Bahir Dar, Hawassa, and Dire Dawa can now avoid travel burdens. For Sisay Tamrat, dean of Wachamo University’s School of Law, the eCourt Ethiopia is a tool that enhances transparency.

“Clients often complained about misrecorded statements,” he said. “This fixes that.”

However, Sisay also warned of digital exclusion.

“If the foundation is weak, the whole system will suffer,” he said. “Connectivity lapses and digital illiteracy could leave many behind.”

Judge Abebe stated the need for a cloud-based architecture capable of sustaining large-scale court operations.

“The system in the courts is strong enough to avoid interruptions during proceedings,” he told Fortune.

The final legal framework, which will govern eCourt Ethiopia, is expected to be finalised within a month. However, experts say that whether a successful pilot phase can scale into a nationwide legal revolution remains to be seen.

“We’re not only building a platform, we’re building a justice ecosystem,” Judge Abebe told Fortune.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...