Ethio telecom’s latest annual performance review painted a picture of rapid infrastructural expansion and commercial resilience. However, behind the growth lies a deepening strain on the country’s ailing energy grid and unresolved questions about financial transparency and market discipline.

In the past year alone, the state-owned telecom operator has added 1,683 new mobile sites, bringing its total nationwide to 10,010. Nearly half of these installations now dot the rural landscape, regions that have long been deprived of basic infrastructure and even access to the national electricity grid.

Last week, Frehiwot Tamiru, CEO of Ethio telecom, presented the results at the Science Museum on Menelik II Avenue, revealing that the network’s user capacity had risen to 104 million, an increase of 35.3 million in a single year.

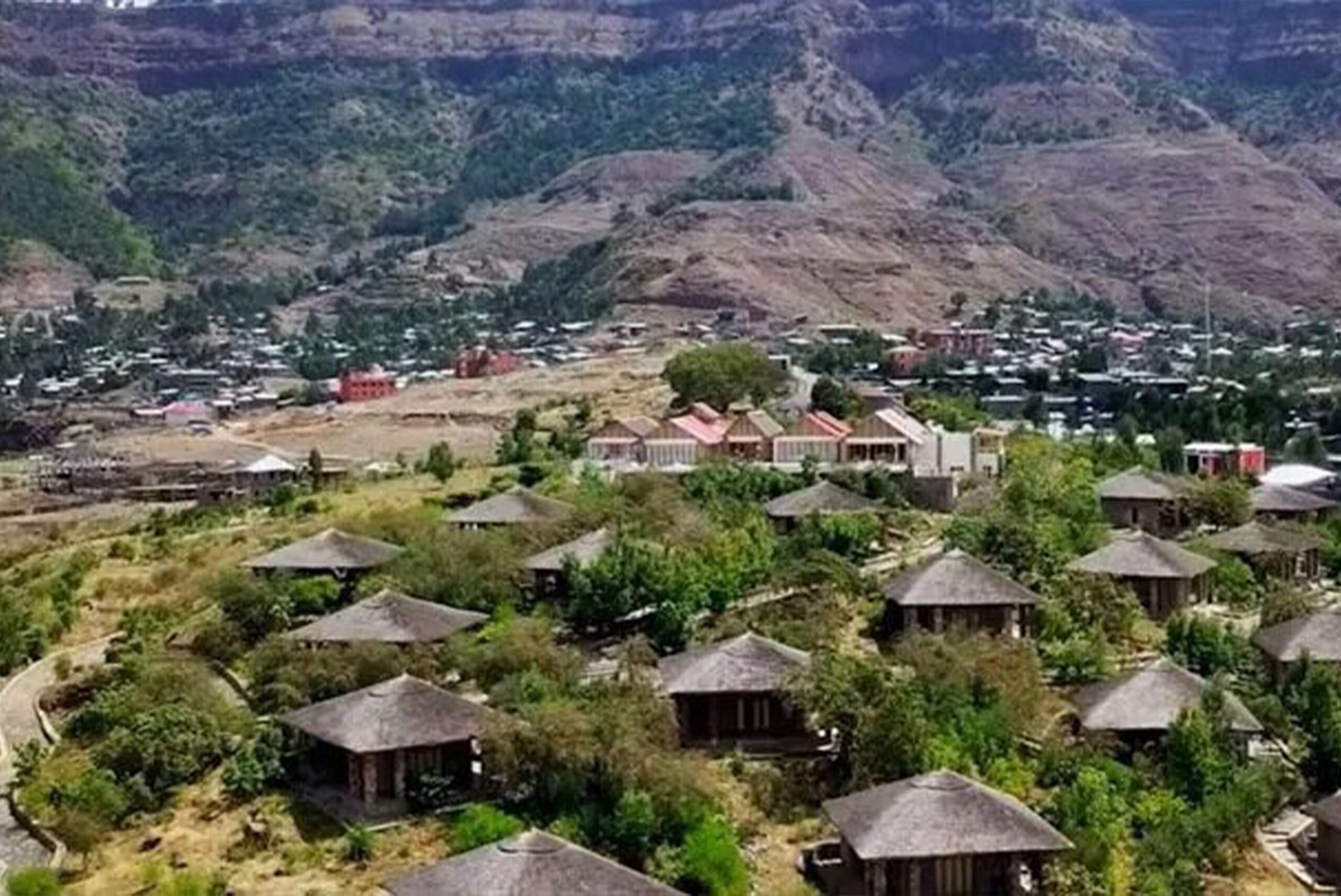

LTE coverage now blankets 936 towns, while 5G services are available in 26 locations, including 16 new towns. The company’s rural connectivity program linked six million people across 2,388 villages, a feat that few government utilities can currently match in reach or pace.

But that very pace now appears to be outstripping the country’s foundational capacity to support it. With 43pc of telecom sites dependent on diesel generators and only 21pc powered by solar systems, the rollout exposed the acute mismatch between the federal government’s digital ambitions and its energy realities.

The company’s heavy dependence on alternative energy sources is no longer a temporary measure.

“Many of these sites are not connected to the national grid,” said Frehiwot.

Ethio telecom increased its solar energy capacity from 20MW to 27MW, while expanding its fleet of backup generators from 3,814 to 4,305 units. These investments, although necessary to maintain service continuity, are both costly and logistically challenging.

Yemanebrehan Kiros, general manager at Yomener Energy Auditing & Engineering Plc, was blunt in his assessment.

“It’s not for economic benefits,” he told Fortune.

He questioned the long-term feasibility of relying on solar and diesel systems, particularly in a country where electricity is heavily subsidised but often unreliable. Yemanebrehan attributed the high capital costs, spatial footprint, and battery degradation to serious drawbacks.

“Efficiency is a virtual dam,” he said, arguing that optimising existing infrastructure would deliver better returns than simply scaling generation.

Ethiopia’s electric grid coverage reaches 25pc of the country’s landmass, and household access hovers at 22pc, figures that underline the gravity of the problem. The average household experiences 35 power interruptions per month, each lasting approximately 21 hours. Distribution losses exceed 20pc, and regional disparities are glaring, while urban areas like Addis Abeba enjoy 93pc access. Rural regions of the Afar and Somali regional states remain below 12pc.

The Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) utility, now scrambling to meet surging industrial and digital demand, faces its own headwinds. It hopes to generate 426 million dollars in export revenue this fiscal year, even as it struggles with voltage fluctuations, overloaded lines, ageing conductors, and environmental interference.

By March 2024, Ethiopia’s generation capacity stood at 4.3GW, driven primarily by hydropower. Ambitions remain high. With GERD and other large-scale hydro projects, the country targets a capacity of 10.7GW by 2027. The federal government expects solar power to comprise 17pc of total generation by 2040.

However, the infrastructural groundwork to distribute this power equitably remains worryingly inadequate.

While the telecom operator basks in operational success, posting 162 billion Br in revenues, a 72.9pc year-on-year (YoY) increase, and a 99pc fulfilment of its annual target, financial analysts are raising concerns over transparency and governance.

A dividend payout of 12 billion Br to the federal government, its sole shareholder, was made without accompanying disclosures on whether the sum was derived from current profits or accumulated reserves.

Frehiwot avoided directly addressing the dividend allocation for the 47,000 new shareholders who bought into the company’s shares this year. She disclosed that registration remains incomplete for one percent of shareholders and that certificates will be issued.

Mesay Woubeshet, a company representative, confirmed that there will be no dividend distribution or shareholders’ meeting this year, citing pending registration. For market watchers, this is a troubling signal.

“Was it based on current-year profits or retained earnings?” asked Mekbib Tesfaye, a London-based analyst, who argued that such ambiguity impacts any reliable assessment of long-term sustainability.

According to Mekbib, a broader issue, such as the lack of detailed financial disclosures, where Ethio telecom has yet to publish unaudited income statements, balance sheets, or cash flow summaries, deprives market observers of tools for independent evaluation.

“If Ethiopia hopes to build a credible capital market, it must enforce transparency standards on its flagship SOEs,” he said.

Adding to the concern is the fate of three billion Birr in new shareholder investments, made in anticipation of privatisation. Without dividend rights, audited returns, or board representation, Mekbib questioned the opportunity cost of those funds.

“They could have earned 300 million to 450 million Br in a deposit account,” he said.

Ethio telecom’s market dominance, especially its low tariffs, has come under scrutiny from new entrant Safaricom Ethiopia Plc, which recently crossed the 10 million user mark. CEO Wim Vanhelleputte warned that current prices are unsustainable.

“This is not profitable for us in the long run,” he said, implying looming tariff adjustments.

Ethio telecom, meanwhile, insisted it offers one of the lowest rates globally, leveraging its scale and entrenched infrastructure to crowd out competition. However, this could raise regulatory questions, particularly in the context of the authorities’ commitments to telecom liberalisation under their broader economic reform agenda.

Beyond digital connectivity, Ethio telecom is also pushing into e-commerce. Its online marketplace, Zemen Gebeya, now hosts 195 active merchants and nearly 3,800 products, processing 7,000 orders worth 15.3 million Br. A modest beginning, but one that signals a strategic shift toward platform economics and value-added services.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...