The experiment with a freely traded Birr, or one managed in a floating manner in practice, was a year old last week, and the numbers tell a story of both promise and fragility.

On July 29, 2024, Central Bank Governor Mamo Mehirtu ended a five-decade fixed-rate regime and let the currency float. In the 12 months that followed, foreign-exchange inflows jumped 33pc, to a record 32 billion Br, according to the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). Goods exports brought in 8.3 billion dollars, services 8.5 billion and remittances nearly 7.1 billion, evidence of demand long suppressed by chronic shortages of the Breen Buck.

Traders who once complained of “arbitrary allotments” now say dollars are at least findable, though the Brewed Buck crunch has grown sharper. Average daily sales of foreign currency to businesses more than doubled, to 25 million dollars, the Central Bank says. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the midwife of monetary and fiscal policy reforms, hard-currency reserves tripled to 2.7 billion dollars, providing officials with a buffer they had lacked for years.

The Central Bank paired the float with quick deregulation. A rule that forced banks to buy Treasury bonds with hard-currency earnings was scrapped, as was a requirement that exporters surrender a fixed slice of dollar revenue. Roughly 10 exchange bureaus opened in Addis Abeba within six months, and more than 850 billion Br coursed through the electronic interbank market by June 2025. Inflation, which had reached nearly 20pc in mid-2024, slowed to 13.9pc by June. The Brewed Buck now trades inside a daily band set by a policy committee chaired by Governor Mamo.

However, not every shackle disappeared. Banks still pay teh Central Bank a 2.5pc exchange commission on each foreign-exchange deal. Smaller importers claim that when large corporations tap into new channels, they are left waiting. Critics warn that without deeper tools, such as forward-contract platforms and interbank credit lines, the gains could be reversed.

Those stresses surfaced during the six trading days from July 28 to August 2, 2025.

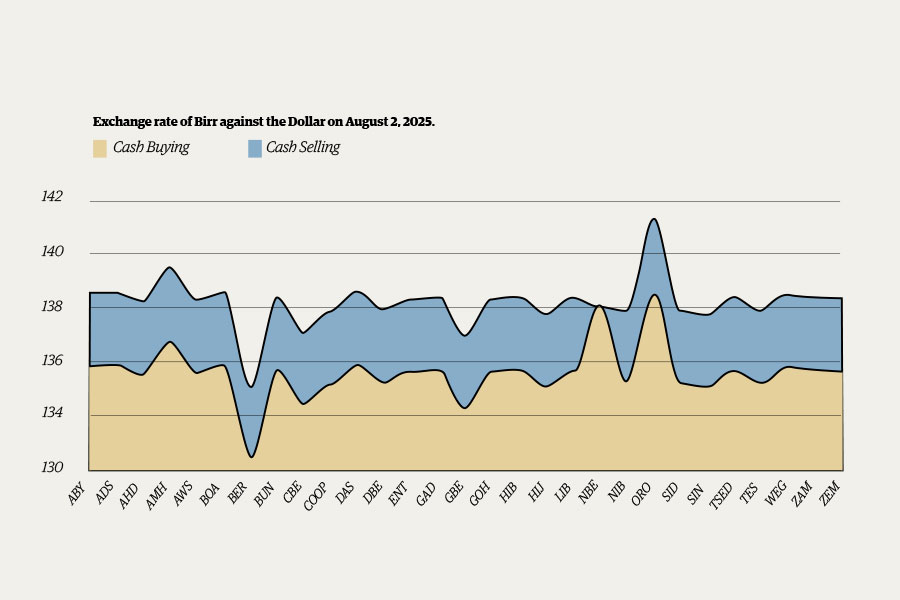

The average buying rate for the dollar inched up to 135.8 Br from 135.3 Br; the average selling rate rose to above 138.2 Br from 137.9 Br. Most lenders maintained the mandated two-percent spread between the bid and ask. Beneath the headline, the behaviour split.

Seven banks, including Berhan, the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), and Global, maintained both rates at their current levels throughout the week. Amhara Bank, posting 136.78 Br for buying, showed a standard deviation of 0.60 Br on bids and 0.61 Br on offers, signalling nimble trading or uneven liquidity. Gadaa Bank’s swings were slightly smaller but still marked it as an outlier.

Volatility sharpened at the extremes. Oromia Bank posted the week’s highest bid, 138.54 Br, on August 2 and the top offer, 141.31 Br, signalling a readiness to pay up for scarce dollars while charging premium margins to favoured clients. Berhan Bank stood at the other end, bidding 132.47 Br and asking 135.11 Br, effectively sitting out of heavy flows. Such gaps show how the choice of counterparty can shift a large deal by more than four Birr.

The Central Bank itself raised eyebrows. On July 31 and again on August 2, it quoted identical buy and sell rates, erasing the spread, an unheard-of gesture under managed-float rules. Market watchers read the move as a public vote of confidence in the new market; others may see it as an effort to squelch arbitrage. Either way, it revealed the tug between discipline and dirigisme at the heart of the reform.

Volume-weighted figures add nuance. Awash and Abyssinia banks, both first-generation private lenders, nudged bids at 136 Br to the low-136s, respectively, a cautious climb that analysts linked to expected policy tweaks. The state-owned CBE and other big institutions stayed more rigid, reflecting conservative risk appetites.

Short-term jitters sit atop a longer depreciation arc. On August 16, 2024, only 18 days after the float, the industry average bid was 104.05 Br. By October 4, it reached 112.37 Br, an eight-birr, or eight percent slide that market observers called “a serious catch-up rally” to close the gap between official rates and real demand. The currency lost another four Birr in the year’s final weeks, slipping from 120.49 Br on November 9 to 124.66 Br by Christmas.

A lull followed. From late December 2024 through late February 2025, the average rate remained between 124.80 Br and 126.13 Br, touching a year-to-date low on February 25. Observers credit limited dollar injections, tighter import flows and behind-the-scenes moral suasion by the Central Bank.

In March, depreciation resumed. By April 12, the rate had reached 128.24 Br; in early May, the Brewed Buck broke the psychological 130 Br barrier. The pace quickened through June, peaking at 135.50 Br on June 20 before easing to 134.42 Br by mid-July. A sudden spike to 137.74 Br on July 9, led by Oromia Bank, showed how thin order books can magnify shocks, even as lenders like Berhan lagged far below the average.

Fundamentals still lean against the Brewed Buck. The chronic trade deficit, widened by imports of machinery, fuel, and fertilisers, outstrips earnings from coffee, gold, and services. Inflation near 14pc discourages savers from holding Birr balances. Without deeper financial plumbing, any external shock could test the new buffer.

Yet, the first-year scorecard offers progress. Businesses now find dollars in far less opaque fashion. Exporters keep more of their revenue. Banks have room to manage liquidity rather than channel it to mandatory Treasurys. Even cautious critics concede the float has added transparency.

The question is whether momentum will last. Forward-contract markets remain absent, and importers cannot lock in rates months ahead. Interbank credit lines are relatively short, so a disruption at one large bank can quickly ripple out. The Central Bank’s zero-spread play may have calmed nerves, but it also blurred the line between regulator and participant.

Small firms already feel squeezed. While dollar sales doubled overall, they say large corporations soak up supply before it reaches the second tier. Bankers counter that without broader reforms, such as electronic documentation for trade finance, the system cannot safely push more dollars downstream.

For Governor Mamo and his policy committee, the next phase may be as tough as the first. The Brewed Buck now trades within a band, but the band’s credibility is only as strong as the reserves behind it and the market’s faith in the authorities’ commitment not to revert to administrative fiat. At 3.1 billion dollars, reserves cover barely two months of imports, well below the conventional comfort zone of 2.1 months.

Still, the float has begun to create winners. Exchange bureaus that never existed under the peg have sprung up in hotel lobbies and shopping malls. Diaspora Ethiopians, once wary of official channels, are now using legal brokers to send remittances because prices have become comparable to those on the street. Almost.

Losses are visible, too. Importers facing tight Birr liquidity pay higher interest rates, and the Central Bank’s fee eats into their margins. Living costs, while easing, remain unprecedentedly high for wage earners who shop with Birr.

For now, the Birr sits at 136 Br, give or take, to a dollar with volatility clustered around big statements from the Central Bank and episodic dollar injections through auctions. A year on, the market is still learning what a floating currency means in a country accustomed to administrative prices. The first 12 months proved that demand was waiting. The next test will be whether supply, discipline and trust can keep pace.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...