Featured | Sep 14,2025

Aug 10 , 2024.

The past few weeks have been anything but uneventful on the economic front. Across the board—from wage earners to business leaders and policymakers—there has been a discernible apprehension as everyone watches the daily fluctuations in the foreign exchange market. The value of the Birr has experienced dramatic shifts, a sharp contrast to the decades when changes in the currency’s value were determined by government decree.

Since 1990, successive policymakers have repeatedly devalued the Birr, hoping to boost the competitiveness of exports. However, the anticipated economic regeneration has remained elusive.

The Birr, which had depreciated by an eye-watering 2,731pc against the U.S. dollar over the past decades, has seen dramatic fluctuations since the market was liberalised. These recent changes alone doubled this percentage, signalling the rough roads of transitioning to a more market-driven system. The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) claimed it was well-prepared for this monumental shift, but the response from the banking industry suggested otherwise.

The state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), the largest in the country, set its buying rate at 74 Br and the selling rate at 76 Br a day after the liberalisation on July 29, 2024. This move quickly became a benchmark for the country’s commercial banks, most of which adjusted their rates slightly higher but remained cautious, maintaining a gap of over 10pc. The special foreign exchange auction held by the Central Bank last week was thus less about making foreign currency available and more about discovering the actual market price of the Birr. The auction revealed a weighted average of 107.9 Br to the dollar, a rate far from stable and likely to fluctuate with broader economic conditions and international market dynamics.

The immediate impact of the floating exchange rate has been felt keenly across the business community. The depreciation of the Birr has introduced a new type of risk — transaction risk — that businesses must now learn how to steer. The days of securing profit margins in the hundreds of percent are likely over, as the macroeconomic reality undergoes rapid and profound changes.

For decades, the economy operated under a regime of strict control. Now, it faces the uncertainties that come with a more open market.

During the military-Marxist era and later under the quasi-market-led policies of Melesites, economic policies were characterised by low gross capital formation, limited domestic savings, an underdeveloped financial system, and chronic infrastructure deficits. In 2023, Ethiopia’s gross capital formation reached 36.29 billion dollars, up from 21.13 billion dollars a decade earlier. However, its share of GDP plummeted from 45pc in 2012 to just five percent. By comparison, Djibouti’s gross capital formation stands at 104pc of GDP, while Kenya’s is at a negligible 0.1pc.

In an economy where foreign exchange reserves are scarce, political connections and networking often determine access to resources. The scarcity has led to widespread economic distortions, with consumers often at the losing end of a value chain dominated by those with the right connections. A rigid currency regime acted as a straitjacket, stifling growth and equity. In contrast, a floating currency and an open exchange market have the potential to free the economy from these constraints, although not without risks.

The debate over the merits of a controlled exchange rate system over a floating regime is particularly relevant for Ethiopia. For 50 years, the country's leaders adhered to a controlled exchange rate system designed to protect domestic industries and support exports. But this approach has also led to a series of economic distortions, including a foreign exchange crunch that has stifled imports of essential goods and raw materials.

Controlled rates mask underlying economic imbalances, making eventual corrections more painful. They are prone to inefficiency and corruption, harming consumers far more than any protection they might offer.

These shortcomings have, in turn, hurt consumers and businesses alike, raising issues about whether a more flexible currency regime might better serve the country's needs.

Understandably, critics of a floating exchange rate argue that it exposes consumers to volatile exchange rates. The depreciation of the Birr has already led to higher import prices, contributing to inflationary pressures in a country where the high cost of living is already a heavy burden on households.

A floating currency's potential to exacerbate poverty and inequality should be addressed as a legitimate concern. A depreciating Birr could increase essential goods prices, disproportionately affecting low-income households. Those with foreign exchange earnings, such as exporters and remittance recipients, may benefit from a weaker currency, while those reliant on domestic income could face increased financial strain. Policymakers will need to strengthen their social safety nets and ensure that vulnerable populations are protected during the transition.

The volatility of a floating currency could also expose the economy to greater external shocks, particularly given Ethiopia’s reliance on agriculture and its underdeveloped financial markets.

However, the potential benefits of a floating currency are substantial.

While exchange rate fluctuations can cause temporary price increases, they could also encourage domestic production, leading to lower prices over time. A freely convertible currency has the potential to attract foreign direct investments, provided that the country's dire political situation is addressed through negotiated settlements. A freely convertible currency shows economic openness and stability, key factors foreign investors consider when deciding where to allocate their capital.

Price discovery, as the central bank tried to determine last week, is another benefit of a floating currency. In an open exchange market, prices reflect supply and demand conditions, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently. A floating currency gives policymakers greater autonomy to implement monetary policies best suited to domestic economic conditions. They can adjust interest rates to control inflation or stimulate growth without being overly concerned about the implications for the exchange rate.

The economy, heavily reliant on agriculture with growing manufacturing and service sectors, will experience varying impacts from a floating currency.

A weaker Birr could benefit the agricultural sector, particularly exports like coffee and oilseeds, increasing farmers’ income. However, the cost of imported agricultural inputs like fertilisers, fuel, and machinery is expected to rise, affecting production costs. In the manufacturing sector, a weaker Birr could enhance the competitiveness of export-oriented industries, stimulating growth and job creation. Yet, it could also increase the cost of imported raw materials and machinery, squeezing profit margins. Confronted with the reality of not transferring prices to consumers, businesses will have to narrow their high-profit margins.

For the service sector, particularly tourism, a weaker Birr could make Ethiopia a more affordable destination for foreign tourists, boosting the industry. However, remittances in foreign currency could decline in value, impacting remittance-dependent households.

The decision to float the Birr appears to be part of a broader and series of monetary policy reforms implemented by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (PhD) administration. These timely, bold and courageous reforms could help correct historical economic distortions and liberate the economy from captivity.

However, the transition to a floating currency will have its drawbacks. A tight monetary policy environment, where the central bank has stopped lending to the federal government and capped credit availability, could dampen demand. Last week’s liquidity crunch in the Birr market is a case in point. The authorities appear willing to accept slower growth as a trade-off for economic stability, but this decision carries consequential social and political risks.

A successful transition to a floating exchange rate will require economic policy reforms and improvements in governance, transparency, and institutional capacity. A credible monetary policy framework and an autonomous central bank will be crucial in maintaining the confidence of domestic and international economic actors.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 10,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1267]

Featured | Sep 14,2025

Featured | Feb 11,2023

Viewpoints | Apr 13, 2025

Commentaries | Jul 10,2020

Fortune News | Dec 02,2023

Fortune News | Oct 23,2018

Commentaries | Jan 13,2024

Viewpoints | Aug 13,2022

Life Matters | Jun 22,2019

Commentaries | Jan 27,2024

Photo Gallery | 179250 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 169445 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 160349 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 137165 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

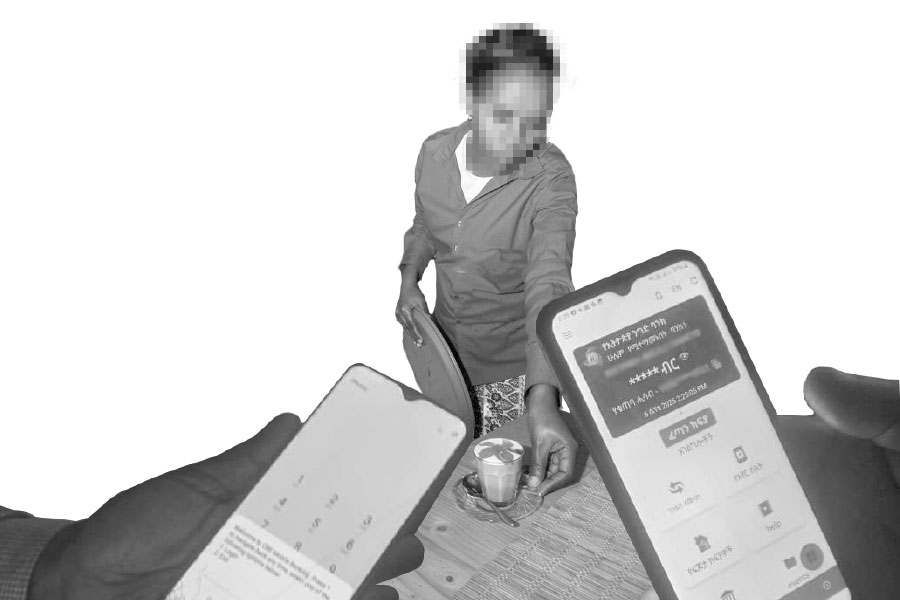

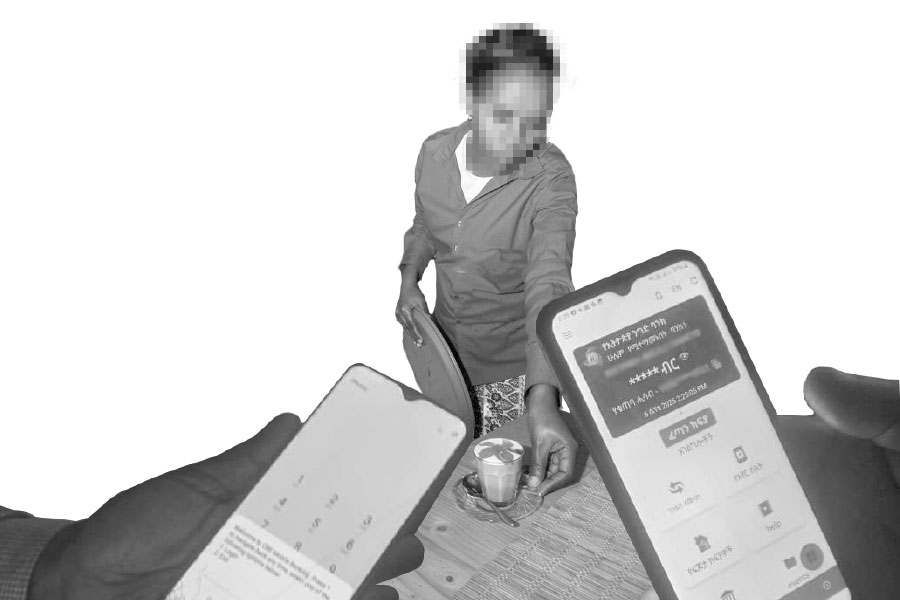

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

Officials of the Addis Abeba's Education Bureau have embarked on an ambitious experim...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The federal government is making a landmark shift in its investment incentive regime...

Oct 29 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) is preparing to issue a directive that will funda...

Oct 26 , 2025 . By SURAFEL MULUGETA

A community of booksellers shadowing the Ethiopian National Theatre has been jolted b...