Editorial | Dec 24,2022

.

When Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) appeared before parliament a month ago, a member questioned the legitimacy of his administration in light of its economic policy divergence from the status quo. The defunct EPRDF campaigned and won on a platform of statist developmental growth, the parliamentarian reasoned, hence the Prosperity Party’s decision to backtrack on such promises in favour of a market-led model puts its legitimacy to govern in question.

It was a criticism that has been leveled at Abiy’s administration before. The Prosperity Party was born on the ashes of the flailing EPRDF coalition, and then economic liberalisation was introduced. The Prime Minister responded with a tone and manner that was ironic, to say the least, if not revealing to his decision-making going forward.

He alluded, rather mockingly, that voters were not given a choice in terms of policies. He wondered aloud with whom could there have been a competition in the first place?

It was a reference to the lack of a strong and organised opposition during the last national elections, a reality Abiy himself can thank for his joining parliament as a federal legislator and for his successful bid for the position of prime minister.

Nonetheless, his argument holds water. Past elections, in the eyes of the public, suffered from a credibility deficit. It would not have otherwise been possible for anti-government protests to break out a few months after the EPRDF and its allies claimed each seat in the federal parliament. A governing party with such an unprecedented mandate could not have faced the kind of backlash the incumbent was presented with shortly after entering public office.

A reform - carefully handled and subtly nurtured as it could have been tacitly agreed upon - was needed to bring about an opening for political liberalisation and credible national elections. There even seemed to be the implicit agreement to allow the “reformers” some latitude to step out of the institutional frameworks and spirit of the Constitution in their endeavour to incorporate sociopolitical and economic groups that had faced exclusion.

The backdrop was civil societies, opposition groups and the private sector - all major stakeholders in the shaping of the state’s behavior - were ostracised by institutions and even the laws of the country. If this was the case, then it made sense to allow a leader imbued with public goodwill to be granted a certain dosage of carte blanche to act on behalf of the reform. So did many believe.

There was even barely any outrage when Abiy went as far as to mediate fractures within religious institutions a few months after his inauguration, a violation of the constitutional provision to strictly separate the affairs of the state and religion. The almost messianic perception he had induced among many of his supporters led them to be blind to some of his earlier flaws.

The promise of reform glossed over the challenges in exercising state power that froze out institutions. Increasingly, it has become personalised, informal and unchecked. Abiy’s ardent supporters remain generous to him, justifying his Napoleon-style leadership as indispensable for the sake of maintaining the momentum this transition presents.

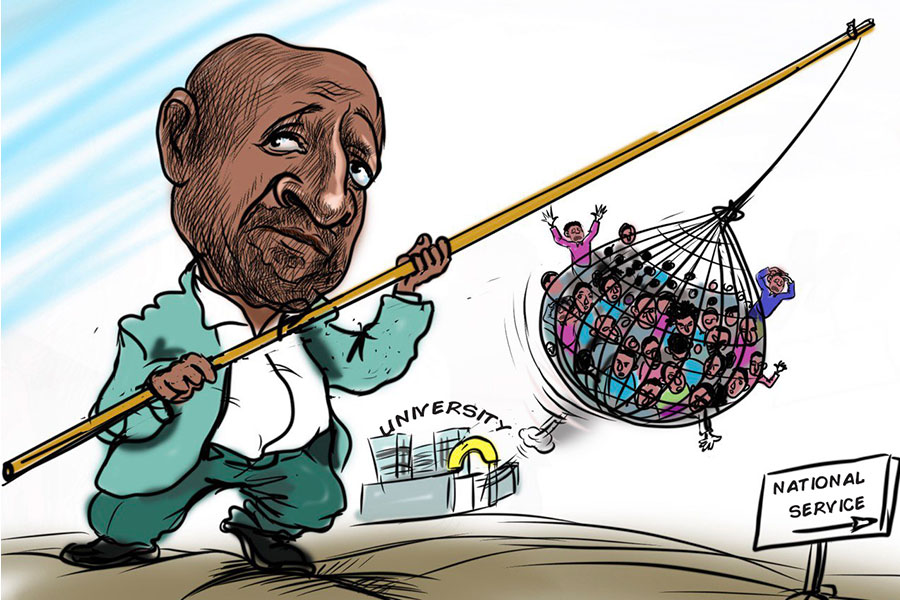

To the disappointment of some who outgrew their passionate support for him, this has contributed to the blurring of what the reform entailed in the first place. If there is any, the current administration was tasked with the singular responsibility of overseeing and nurturing a transition - opening the political space, reforming judicial and electoral laws and the strengthening of democratic institutions - that would allow for competitive national elections. What was thought to follow was the acid test for an incumbent to courageously accept the popular will, regardless of whether or not it displeases those who hold political power.

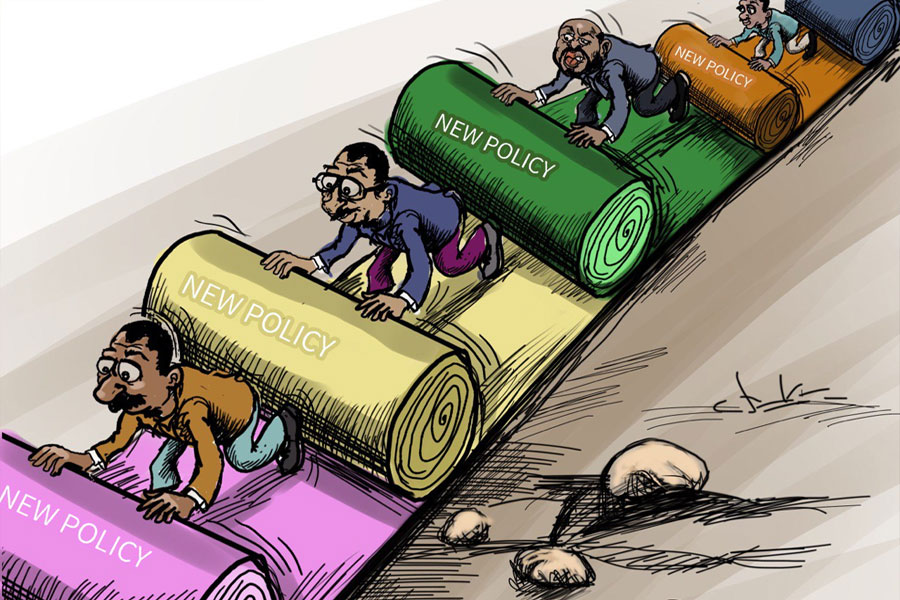

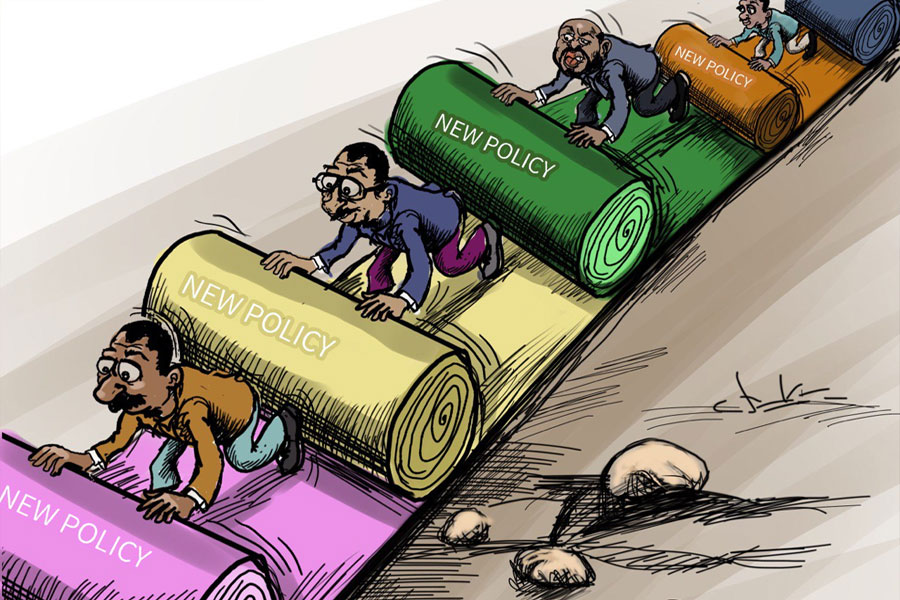

But recently, Prime Minister Abiy’s administration has been overstepping its bounds. It has taken it upon itself to implement policies likely to affect the country for generations to come. These include backtracking on a long-held strategy not to allow mediation by third parties in negotiations concerning the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the deals Ethiopia is entering with multilateral financial institutions.

No doubt these deals will have consequences for many segments of Ethiopia’s society, hence their implementation requires a strong popular mandate.

The dilemma faced by transitional incumbents, when it comes to economic and political issues that cannot be postponed, is understandable. Postponement of the filling and operation of the Dam, for instance, on a project that has already been delayed by three years, would be impractical as it would be wasteful.

But it is not clear why the administration would agree to talks observed by the United State and the World Bank, reversing Ethiopia’s almost decade-long stance on the involvement of third parties in any manner. That it remains unclear what Ethiopia was willing to give up in return, if anything, or what the public would be willing to accommodate makes it sound worse. The consequence has been a deeply flawed and naively sought-after negotiation process that carries the risk of robbing the country of its right to make decisions over its resources.

In the same token, Abiy’s administration was faced with a macroeconomic crisis, where inflation was in the double-digits, export revenues were stagnating, and unemployment was surging. It had to manoeuvre to address the problem at least in the short term. This was especially crucial considering how these economic malfunctions contributed to political volatility.

The response by the administration was initially a measured policy prescription aimed at making the business environment more conducive. But the administration has also, over the past year, set out to strike deals with multilateral institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in return for billions of dollars in loans and economic assistance.

Usually, multilateral financial institutions insist on deep structural economic adjustments for countries to qualify for such assistance. In the words of Ahmed Shide, minister of Finance, generous financial aid and large loans depend on Ethiopia meeting "certain reform measures."

Economic reforms, justifying large bilateral and multilateral assistance packages, are usually structural and likely to have consequences for generations. It would have been a much less questionable policy to undertake and implement had the administration obtained a mandate through national elections.

There is a great amount of leeway given to the exercise of power by the Prime Minister and his office. But the executive also has the duty to earn its mandate when undertaking decisions likely to have immense consequences on the lives of citizens for generations to come.

The least the administration could have done here is make public the details of the various agreements. It would be ideal to maintain the status quo and postpone decision-making until after the elections in August 2020.

Ethiopia’s history is full of lessons as to the fate of national endeavours citizens do not feel they have ownership of, either because they were never adequately consulted or because the incumbents lacked the mandate. It would be a tragedy if the same fate awaited positive measures, such as economic liberalisation, that are being undertaken.

Without earning the endorsement of the popular will, Abiy’s administration is merely tweaking the fundamentals without the certainty that they will last. This makes the implementation of such crucial policy measures difficult if not fatalistic.

PUBLISHED ON

[ VOL

, NO

]

Editorial | Dec 24,2022

Fortune News | Jun 08,2024

Fortune News | Jun 01,2019

Viewpoints | Jan 12,2019

Commentaries | Sep 13,2025

Fortune News | Jun 29,2025

Radar | Jul 13,2025

Editorial | Apr 13, 2025

Viewpoints | May 31,2025

Radar | Jul 17,2022

Photo Gallery | 174245 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 164470 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 154625 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136655 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 12 , 2025

Tomato prices in Addis Abeba have surged to unprecedented levels, with retail stands charging between 85 Br and 140 Br a kilo, nearly triple...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A sweeping change in the vehicle licensing system has tilted the scales in favour of electric vehicle (EV...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A simmering dispute between the legal profession and the federal government is nearing a breaking point,...

Oct 12 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

A violent storm that ripped through the flower belt of Bishoftu (Debreziet), 45Km east of the capital, in...